On November 14, police in Thai Binh province detained a National Assembly delegate, Luu Binh Nhuong, on suspected charges of corruption. The accusations are odd, but it appears that Nhuong has been charged with illegally mining sand and forcing businesses to buy it, and has been linked to someone already convicted of a similar crime.

But the news came as something of a shock. Radio Free Asia quoted a former director of the Central Internal Affairs Commission as saying, “I was surprised that it was a person who has long been praised by the public as one of the very rare National Assembly deputies with a very strong voice defending what is right in the National Assembly.”

One academic tweeted that Nhong was a “dedicated Vietnamese statesman” who is “well-respected in the Vietnamese legal community for pushing back wrongful convictions and death sentences.” A journalist tweeted: “Shocking arrest on 14 Nov of a former member of VN parliament, Luu Binh Nhuong, who was very much liked for his straightforward, slightly populist public statements.”

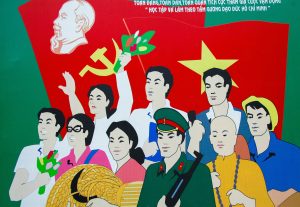

Nhuong, a long-term lawmaker, was a member of the National Assembly’s Social Affairs Committee and is currently deputy head of the Assembly’s People’s Petitions Committee. He has been rather critical of the government’s recent actions, with a particular ire for the Ministry of Public Security. That had led some to think this was an act of political revenge. But it’s perfectly logical as part of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV)’s ongoing anti-corruption campaign, which has revealed, contradictorily for its architects, that the rot of graft exists throughout the Party – although the current top brass will never admit that the problem is actually the CPV and its one-party system, not the tens of thousands of apparent bad apples that have been disciplined or jailed for graft since 2016. When people like Luu Binh Nhuong are arrested for corruption, one has to start to think that the problem maybe is the system. Who else is corrupt? Maybe everyone.

The anti-corruption campaign has been complex and, at times, contradictory. (This columnist has been struggling to finish writing a book about it for months). At its basest level, it is about stopping the hemorrhage of state money. But it’s more existential than that. In the 2010s, a group of Communist Party leaders centered around then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung saw that the Party could maintain its absolute authority by becoming a conduit to power and wealth. Anyone who wanted to get ahead, either in business or promotion in the civil service, had to pay “rent” to the CPV elites. Hence, Dung and his ilk became known as “rent-seekers.”

It was thought that the expanding private sector, which might have grown powerful enough to demand reforms from the Party, such as independent courts, the rule of law, and private property, would be constrained because it was indebted to the CPV’s patronage and because it had to compete to gain the allegiance of sparring grandees within the upper echelons of the Party, who became fabulously wealthy. At one point, Dung was rumored to be the richest person in Vietnam.

In doing so, however, the CPV was beginning to more closely resemble a regular authoritarian regime, devoid of any ideological underpinning or sense of historical mission. This was anathema to Nguyen Phu Trong, who spent most of his career in the Party’s theoretical wing as editor of the Communist Review. Although elected CPV general secretary in 2012, Trong was in a weak position. The tables turned in 2016 when he warded off Dung’s attempts to become general secretary.

Shortly afterwards, Trong launched the anti-corruption campaign, bringing down thousands of party and government officials and private sector tycoons. Trong also enacted a “morality campaign” to reassert socialist principles as the basis for promotion through the party ranks. As such, the anti-corruption campaign has several objectives. First, the campaign aimed to purge the party of non-ideological officials and those who only joined for social advancement, thus restoring ideology, not money, as the glue that binds the Party.

Second, it prosecuted those whose corrupt practices were losing the state a fortune. Third, it was intended to alter the dynamics between the CPV and the private sector. The Party no longer asserts its authority by being a conduit for non-members to enrich themselves or rise through society. Now, it seeks to assert its power over the private sector through fear and prosecution – indeed, even through prestige, in that the CPV now presents itself to society as the force tackling the vice of corruption, a campaign popular amongst the general public. It wants the private sector separate and intimidated, not enmeshed and confident, as in Dung’s days.

But all of this will have diminishing returns in the long run, mainly because Trong and his ilk appear to think that corruption is a quirk, a mistake, of the one-party system, rather than its essence. As Trong said, he wants to catch the mice without breaking the vase. He’s never seemingly considered that there might be something about the metaphorical vase that has bred so many dodgy mice.

So, instead of changing the institution, Trong thinks he can change human nature. There’s a long list of past communist leaders who thought they could do the same and failed. Aleksandr Zinovyev’s satire of Homo Sovieticus was prescient because that was what Moscow wanted to create, just as Che Guevara’s obsession with a “New Man” – a consciousness built upon morality, not material incentive – meant he could not impose within others the finest qualities he saw in himself.

Similarly, Trong seeks to recreate the CPV in his own image: austere, serious, ideological and driven by an arrogance of thinking himself purer than his colleagues. It is, at the same time, reactionary, in that Trong, 79, wants to recreate the morality of Ho Chi Minh’s era when life in Vietnam really was austere and socialism was taken seriously – and idealistic – in that he sees progress through the changing of human habits, not social structures. Hidden behind all that, though, is naked authoritarianism. His concern isn’t the immorality of corruption per se; it’s the system of corruption of the early 2010s, which could have led to alternative sources of power, like the private sector, rivaling the CPV for authority.

Trong has also made himself a hostage to his own campaign. If, as he says, the CPV must rid itself of the non-ideological and corrupt, it can only be done if someone with the same motivation rules the institution. However, he has clearly not found a successor whom he can trust to continue his project, which is why he is now serving a third term as general secretary, the first person to do so since the death of Le Duan in 1986. It’ll be interesting to see if Trong can decide on a successor in 2026. Perhaps not. Perhaps he has grown too paranoid about the institution he is supposedly trying to purify.

Your columnist has recently had a problem with mold in his house. At first, I saw it on a few cupboards and photo frames. Then I started seeing it on other furniture and in other rooms. Expensive products were bought to clean the affected parts. But, still, it spread – and the more I looked, the more I saw. Perhaps the mold had been there for longer than I imagined. Maybe it was my fault; had I been improperly airing the rooms or not checking the furniture enough in the past? Maybe it was an unavoidable feature of living in a converted farmhouse in a damp country.

Eventually, some furniture was thrown out, although this probably won’t solve the problem in the long run. There’s now consideration of whether to move house entirely, although that will be arduous. The reader might not be particularly interested in my woes, but the point is that sometimes the rot cannot be cleaned; sometimes you have to accept that the rot was your fault, that you cannot stop it in the same environment that bred it, and perhaps it’s time to get rid of the furniture and start anew. Trong, who likes to speak in parables, would perhaps understand the analogy.