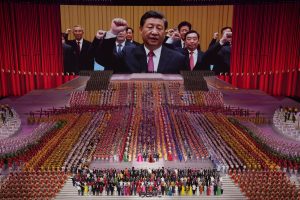

It has become a truism that Xi Jinping is the most powerful leader in China since Mao Zedong. In 2016, a Times Magazine cover showed an image of Mao behind a peel-away picture of Xi, implying Xi is the second coming of Mao. In analyzing Xi’s centralization of power and personality cult, many articles from the New York Times to Al Jazeera have declared that Xi is the new Mao.

Xi is the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao because he is unconstrained by the party norms and institutions of the post-Mao era, which were designed to prevent the emergence of a Maoist personalistic leader.

After the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao, China entered an era of political institutionalization. Deng Xiaoping believed that no Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader should repeat the Maoist mistake of power over-centralization. In addition, Deng faced constraints from party seniors such as Chen Yun, Yang Shangkun, and Li Xiannian. Therefore, Deng had to build coalitions to lead effectively.

As Susan Shirk showed in her study on China’s economic reform, Deng established a pro-reform coalition of provincial governors and light industry managers to wrestle power away from pro-Maoist heavy industry managers and the military-industrial complex. To sustain the reform, Deng allowed the pro-Maoists to take advantage of new economic growth and successfully expanded his winning coalition to inland provinces and heavy industries.

Since the Deng period, elite politics in the CCP experienced a series of institutionalizations in retirement, succession, and transition. Deng Xiaoping first set the example of retirement, ending the life-long tenure of CCP leaders. Jiang Zemin lowered the retirement age to 70 in 1997 and 68 in 2002 to eliminate his political opponents like Qiao Shi and Li Ruihuan. Deng established the succession norm in 1992 by appointing Hu Jintao to the Politburo Standing Committee.

This move not only set the rule of cross-generational appointments but also established the norm that successors must sit in the Politburo at least one term before their eventual succession. In addition, the successor often took the role of vice president and vice chairman of the Central Military Commission and joined important Leadership Small Groups to gain valuable experience and earn credibility among other influential military and civilian leaders.

As a result of these institutionalization attempts, China developed a collective leadership style. During the Hu era, elite politics evolved into a “one party, two factions” system. The Youth League faction, or Tuanpai, headed by Hu Jintao, included cadres from humble backgrounds who gained promotion through the Youth League system and started their careers in poor inland provinces.

Another faction was the princelings or Shanghai Gang under Jiang Zemin. They were children and relatives of revolutionary heroes and former leaders. Many, such as Zeng Qinghong, forged connections with Jiang in Shanghai.

Tuanpai and the Shanghai Gang preferred different policies. Jiang’s policies were pro-economic growth, pro-coastal, and pro-urban, which included the state-owned enterprise reform that led to high unemployment and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization. Jiang and the princelings also supported limited political reform, such as moves toward consultative politics. In contrast, Hu’s policies, such as establishing a basic welfare system and eliminating the rural tax, improved social equality and lifted the living standards of the poorest population.

When Xi Jinping came to power, he had the mandate to centralize power. Many CCP seniors viewed the Hu era as chaotic and corrupted, and the Bo Xilai scandal further cemented their view. They diagnosed the problem as a weak leader who could not effectively control the CCP. Therefore, they believed that China needed a decisive leader with centralized power to tackle China’s emerging problems, such as inequality and corruption.

However, Xi went so far as to obstruct the previously established rules and become unrestricted by any norm, institution, or senior. He swept away term limits and opened the possibility for life-long tenure. He also ended the two-faction system by packing the Politburo Standing Committee with his confidants. The fact that he took away both Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin’s “core leader” title in the third History Resolution, especially when Jiang was still alive, further demonstrated his unmatched power.

As a result, Xi has amassed power to an extent unmatched since Mao’s death. But that does not mean Xi is similar to Mao.

They have different governance styles. Elizabeth Perry discussed Mao’s governance style as mass mobilization. Mao selected models and expected the entire country to follow. Xi also used campaigns to achieve goals, such as rural poverty elimination and containing COVID-19. However, these campaigns were more in line with what Perry described as “managed campaigns” of the post-Mao era, which delegated more power to local bureaucracy and allowed more local variations in implementation. In other words, while Mao used mass campaigns to bypass the bureaucracy, Xi relies on the bureaucracy to implement campaigns.

Mao hated the bureaucracy. He constantly worried about the over-bureaucratization of the Chinese system, which he feared would lead to Soviet-style revisionism. Therefore, he launched the Cultural Revolution to strike the bureaucracy and purged “Chinese Khrushchevs” like Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, who sat at the top of the buraucratic apparatus.

Xi recognized the problems of bureaucracy; he addressed these problems through the anti-corruption campaign. However, unlike Mao, Xi still relies on the bureaucracy for policy implementation.

Rather than relying on the masses in his campaigns, then, Xi aims to use campaigns to change the policy preferences of cadres. For example, Xi’s focus on environmental issues led to decisive measures in environmental regulation campaigns. The campaign aimed to ensure lower-level compliance by making environmental targets vital in the cadre evaluation.

However, Xi still faces the problem of bureaucratization and formalism. As Iza Ding has shown, officials can display their hard work and good intentions even if they fail to make an impact in areas highly prioritized at the center, such as environmental regulation. In general, Xi’s reliance on bureaucracy to implement policy means he could not escape the fragmentation of Chinese politics.

The failure to take account of China’s political fragmentation leads to one of the biggest misunderstandings of Chinese politics: the mistaken belief that China is a unitary state. When discussing Chinese foreign policies, many China watchers tend to believe Chinese policy reflects the leader’s personal preference. For example, Rush Doshi’s “The Long Game” uses central government work documents to show China’s foreign ambitions. Doshi argues that China’s foreign policy under Xi reflects a decades-long strategy to replace the United States as the new regional and global leader. Similarly, Elizabeth Economy’s “The World According China” studies Xi Jinping’s personal speeches and writings to illustrate China’s ambitious new strategy to reclaim the country’s past glory and reshape the geostrategic landscape.

These works make valuable contributions to studying Chinese politics through document analysis, one of the oldest methods for scholars to study the CCP. However, they fail to differentiate between the leader’s input in policymaking and the final policy outcome. China faces a fragmented authoritarianism problem. Therefore, policy outcomes often do not reflect the leader’s intention because many actors are involved in policy implementation.

Andrew Mertha’s “Brothers in Arms” showed that China’s foreign policy has been fragmented since the Mao era. This fragmentation allowed the Khmer Rouge, who had no leverage due to their reliance on China, to resist Chinese policies by exploiting China’s inter-agency fragmentation.

Even Xi’s signature foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has faced this dilemma. Ye Min showed that the BRI is a mobilization campaign – it incentivizes Chinese companies to invest in foreign countries. Similarly, C.K. Lee called the BRI a “red banner” that companies could follow. However, in practice, the BRI implementers, such as Chinese SOEs, often place their interests ahead of national interests, which leads to messy project executions and problems such as corruption. Chinese SOEs have their own motivations and initiatives, which means the BRI’s results have skewed away from Xi’s vision.

In addition, many domestic players act as lobbyists in China’s foreign policymaking. Local leaders have proven adept at citing central leaders’ rhetoric to advance their own distinct goals. Domestic actors persuade and mislead leaders to take positions with their interests in mind.

For example, Yunnan provincial leaders propagated the concept of the “Malacca Dilemma,” which claimed that the U.S. blockade of the Malacca Strait would paralyze the Chinese economy. Yunnan’s goal was to push for the infeasible Sino-Myanmar pipeline project, bringing economic growth, central investment, and corruption opportunities to Yunnan. The Yunnan government mobilized local university professors and People’s Liberation Army leaders to communicate this idea to the central government officials and leaders. In addition, Yunnan formed a powerful coalition with China National Petroleum Corporation, which would become the chief project executor, to lobby for the pipeline project.

The decade-long intense lobbying effort produced fruitful results. Hu Jintao first adopted the Malacca Dilemma narrative in 2003, despite relatively strong relations between the United States and China at the time. The Sino-Myanmar pipeline also became a major BRI project under Xi Jinping.

Xi is the most powerful leader since Mao, yet they govern differently. Xi cannot overthrow the bureaucracy; he must rely on it to deliver policy results. Despite Xi’s efforts to centralize power and exert more control, he still cannot control policy outcomes due to fragmented authoritarianism.

The imagining of China as a unitary state misses this fragmentation. By believing every policy comes from Xi, U.S. policymakers grow the dangerous tendency to assume the worst of China. As the balloon incident showed, China’s fragmentation leads to unintended consequences, and assuming the worst of Beijing’s intentions can lead to an unwanted and dangerous escalation of tensions.