This past weekend marked the 39th anniversary of the deadly night when methyl isocyanate, better known as MIC, smothered Bhopal in central India.

The contamination area was estimated to affect almost half a million people. The dense, highly toxic chemical used in pesticides burst from a local factory and went on to swiftly and silently kill thousands of people almost immediately. In the following years, it has directly and indirectly contributed to the deaths of thousands more. Those who survived suffer daily with a wide range of debilitating conditions, cancers, and shortened life expectancies, searching for any relief they can get without a clear medical solution.

“When I first came to Bhopal, a lot of people told me that the people who died that night were lucky. The ones who are left behind are the unlucky ones because they are bearing the brunt of not knowing what would make them feel better,” said Rachna Dhingra, who works with survivors of the early December 1984 disaster at the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal. She has worked as a campaigner for the Bhopal Group for Information and Action for more than two decades.

During her student years at the University of Michigan, Dhingra first came into contact with the fallout of the disaster after meeting Bhopal survivors and doctors who had come to speak at a shareholder meeting of Dow Chemical, which purchased Union Carbide in 2001. “I was shocked to hear that close to 19 years after the disaster … how dire things were in terms of healthcare, contamination, and justice,” she said.

A frontal view of the abandoned former Union Carbide pesticide plant which has not been secured or dismantled since the accident. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

In 2003, she moved to Bhopal where she has been for the last 20 years, dedicated to helping survivors with legal issues, access to health care, contamination, and striving for victims to “live a life of dignity.”

“Like most people who hear about Bhopal, they associate it with something that happened a long, long time ago, a terrible thing and that was it,” Dhingra said.

But that is far from the reality. Bhopal’s recently dubbed status as India’s third cleanest city doesn’t match with current conditions on the ground for most of its poorest residents.

A view of the abandoned Union Carbide factory and its flare tower, which released the toxic gas that night over Bhopal. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Worse Than We Thought

In a new long-term study conducted using data from the state of Madhya Pradesh, in which Bhopal is the capital, published this year by the University of California San Diego, the aftermath of the disaster is much more wide reaching than was previously understood. The research was done using entirely publicly available survey data from 1999 and 2015.

UCSD economist Gordon McCord, a co-author of the study, explained, “there has been a broader shock beyond the immediate chemical poisoning.” He noted that the shocks radiate “further out than we previously thought.”

Bhopal’s water contamination is widespread throughout the city. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

The study focused on a specific population of children still in-utero and found three key consequences they later faced as adults. “That cohort of in-utero children compared to the children who were significantly older when the disaster happened had higher cancer rates by 2015. They also had a higher likelihood of having a disability that prevented employment, and lower levels of education compared to their peers who are just one or two years older or younger… who might have been living a little further away from Bhopal,” said McCord.

“When you have a disaster like this, obviously there’s an effort to look at the morbidity and mortality right after the disaster happened and for society to decide what the appropriate compensations and programs should be. What we learn here is that we really should be looking at the cost over quite a long run and have a more expansive definition of the population than we tend to look at,” McCord added.

McCord hopes this research can help affect the situation not only in Bhopal, but anywhere governments seek to make it attractive for foreign companies to invest in similar projects. “In the process of economic development and the process of industrialization, there is this risk of overlooking regulatory and safety investments because they are deemed to sacrifice or slow down this process or make you uncompetitive relative to some country that is not going to be investing in some kind of regulatory and safety processes,” he said.

“We are not going to understand some of these impacts for a very long time and we won’t really understand the mechanisms,” he continued.

McCord believes that a line can be drawn connecting people who are disabled today and can’t work, and who were in utero at the time of exposure.

McCord added that the Indian government has not responded to this new research.

A small memorial statue across the street from the factory for the victims of the disaster. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

An Ongoing Health Nightmare, Full of Unknowns

“Union Carbide never revealed the toxicology of gasses that leaked on that night, keeping it a trade secret until today. Here doctors do not know how to treat people, there is no sustained relief for people,” said Dhingra.

Without such knowledge, treatments are only of symptoms with little long-term relief. Some have breathlessness, and take inhaler after inhaler, painkiller after painkiller. People in Bhopal have consumed medicine by the kilogram, antibiotics, and psychotropic drugs, anything in search of relief.

“There are ten times the rates of cancers, huge kidney problems for patients because they have taken so much medicine, and there is no sustained relief,” she said.

Elderly patients show up in the morning at the Sambhavna Trust Clinic in Bhopal to be seen by doctors. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“That is how it has continued. The worst affected people are getting the least compensation. The whole settlement cost Union Carbide not even 50 cents per share. A disaster like this in any other place would have made the company fold,” she argued. Instead, Union Carbide persists, since 2001 under the umbrella of Dow Chemical.

In Bhopal, the disaster has continued to play out for people in various ways. For the generation of children who were between 8 and 16 at the time of the disaster, many had to quit school because their fathers were no longer able to do heavy manual labor because of exposure. “This meant they became the breadwinners in the family. There is a whole generation in the worst affected communities especially where 70 percent of people were daily wage laborers,” Dhingra says.

Dhingra says a great number of those children, now in their mid 40-50s, are dying untimely deaths due to various illnesses, mental stress, and a high rate of suicide.

Elderly patients wait to be seen by doctors at the Sambhavna Trust Clinic in Bhopal. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“There is a total disconnect between the needs of the survivors and what the government has been doing. Even though there were more than two dozen research projects to look into the problems affecting the gas victims by the Indian Council of Medical Research, all of those projects were stopped, and in 1992, without telling a single person what was wrong with them after all kinds of studies were done,” she said.

“Union Carbide continues to hide that information and continues to hide the recent publications they carried out on long-term impacts on exposure to MIC, even on rats or on humans. We know they have the data,” she added.

There is an entire community adjacent to the factory; it is largely a slum. There, 9 out of every 10 people have received what the authorities dub total compensation. Their injuries are categorized as a minor health incident they have recovered from – that is not the reality.

A man sells vegetables in a neighborhood directly across the street from the factory. Contamination of water across the city of Bhopal has been well documented. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“UC fully knew that exposure to MIC would result in residual injury. When you have that data and you tell the Indian government on purpose that there will be minor injuries, it is fraudulent,” Dhingra said.

“The power of the perpetrators versus the power [of those] affected is so massively imbalanced. 70 percent are poor, 50 percent are marginalized Muslims largely discriminated against, and 50 percent are Hindus from the lowest caste, and are considered dispensable. They are fighting one of America’s largest corporations,” she continued.

Five female gas-affected patients wait to be seen by doctors at the Sambhavna Trust Clinic in Bhopal. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

New Developments in Bhopal Courts

In September 2023, a dozen U.S. lawmakers, led by Rashida Tlaib and Pramila Jayapal, wrote to the U.S. Department of Justice urging the department to serve “India’s legal summons upon Dow” and thereby ensure the company would finally appear in an Indian court.

“Finally it was served and Dow appeared on October 3 through lawyers as a partial appearance. This is their old argument where they are contesting the jurisdiction of Indian courts. Dow knew they weren’t allowed to carry on their businesses but they did it,” Dhingra said.

This turn of events is significant, because “this is the first time in 36 years that a foreign corporation/individual has actually shown up in a Bhopal court,” Dhingra said.

A board showing the number of patients who have been at the Sambhavna Trust Clinic in Bhopal. The clinic treats adult gas and water contamination victims with traditional medicine and ayurvedic therapies. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Nesreen and Sekina are two of the thousands who have endured major trauma in the poisonous landscape of Bhopal. When she moved to the city, Sekina found the cheapest place available, unluckily right behind the factory in a neighborhood full of gas victims and contaminated water.

“I had two daughters when I moved there and gave birth to a son in Bhopal. After a few years, one of my youngest daughters started to lose her voice. We took her to many places to find out what was happening, but no one could tell us why. And after a few years she lost her voice altogether. She thinks she lost her voice because of the contaminated water like many other people in the neighborhood,” Sekina recounted.

Sekina, lives right behind the plant, and has suffered from the consequences of Bhopal’s severe water contamination. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Dhingra met Nesreen in 2006 when they walked to Delhi from Bhopal over the course of 37 days, campaigning for clean drinking water for the city. “The prime minister did meet with us and allocated money for clean water, but it did not reach here until 2012,” Dhingra said.

Multiple generations of Nesreen’s family have been affected by the disaster. Her father, once a horse cart puller, could no longer work after his exposure to the disaster and eventually died of tuberculosis in 1994. In Bhopal, the rates of TB are extremely high and the disease affects the immunocompromised even more severely. COVID-19 was five to six times more deadly for gas victims in Bhopal.

“At least six people in my family died of cancer,” Nesreen said.

Nesreen said that every one of her living family members suffers from serious health problems. “I have been working with [Bhopal Group for Information and Action] since 2005, and have seen a lot of people in the affected communities fighting similar battles to attain healthcare. At the gas relief hospitals, which are supposed to provide medical treatment, they often don’t, so we go to [other] hospitals which are not providing appropriate medicine or care to gas victims, or if necessary, resolve it through the courts,” she said.

Nesreen, a gas victim herself, advocates for others in Bhopal. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A New Generation of Suffering

While there are programs for adults to access treatment, a new problem has emerged among the younger generation. In 2006, Champa Devi Shukla started Chingari Trust, which works for the rehabilitation of children born to victims suffering from congenital defects. “So many children were being born with serious issues, and then children started being born like this in our own family,” she said. Her nephew was born completely disabled and another was born with a cleft lip.

She knows the children that come to her center are just a fraction of those that need to be treated. “There’s still a lot of work to do. Not even 1 percent has been done. First, there needs to be proper research on how they can stop such birth defects. And there should be a proper rehabilitation center, with therapies and special education children need to live their life normally.” The number in need is huge, and they have to turn away children if they are over the age of 12, she said. “We feel helpless that our own government does not act, and angry that a multinational company will do this and get away with it.”

A mother works on exercises with her child at the Chingari Trust center. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A physiotherapist at the clinic showed me how she works with young children who suffer from the effects of a disaster four decades ago.

“We are treating people here who are second and third generations of gas-affected people. The worst defects which I see on a daily basis with children include genetic defects, seizure disorders, autism, Cerebral Palsy, and paralyzed children. They all need very vigorous therapies. These disorders come from the MIC,” the physiotherapist said with certainty.

No public studies have found sufficient, direct evidence to support this broad claim, but to healthcare workers like her, it is obvious from the cases she sees everyday there is a major and growing problem in Bhopal. “The common thread among all of these people is that they are all children of parents or grandparents who were gas or water contamination victims,” Shukla said.

Looking for Relief

Satinath Sarangi has for decades helped run a clinic that sees hundreds of adult gas and water contamination victims per day. As the managing trustee at Sambhavna trust clinic, Sarangi has been in Bhopal since the early days after the disaster.

“Initially, I was under the impression that the disaster was small, but when I came here, it was mind numbing,” he recalled. For the first three days he was carrying victims, putting them into vehicles, and rushing them to hospitals.

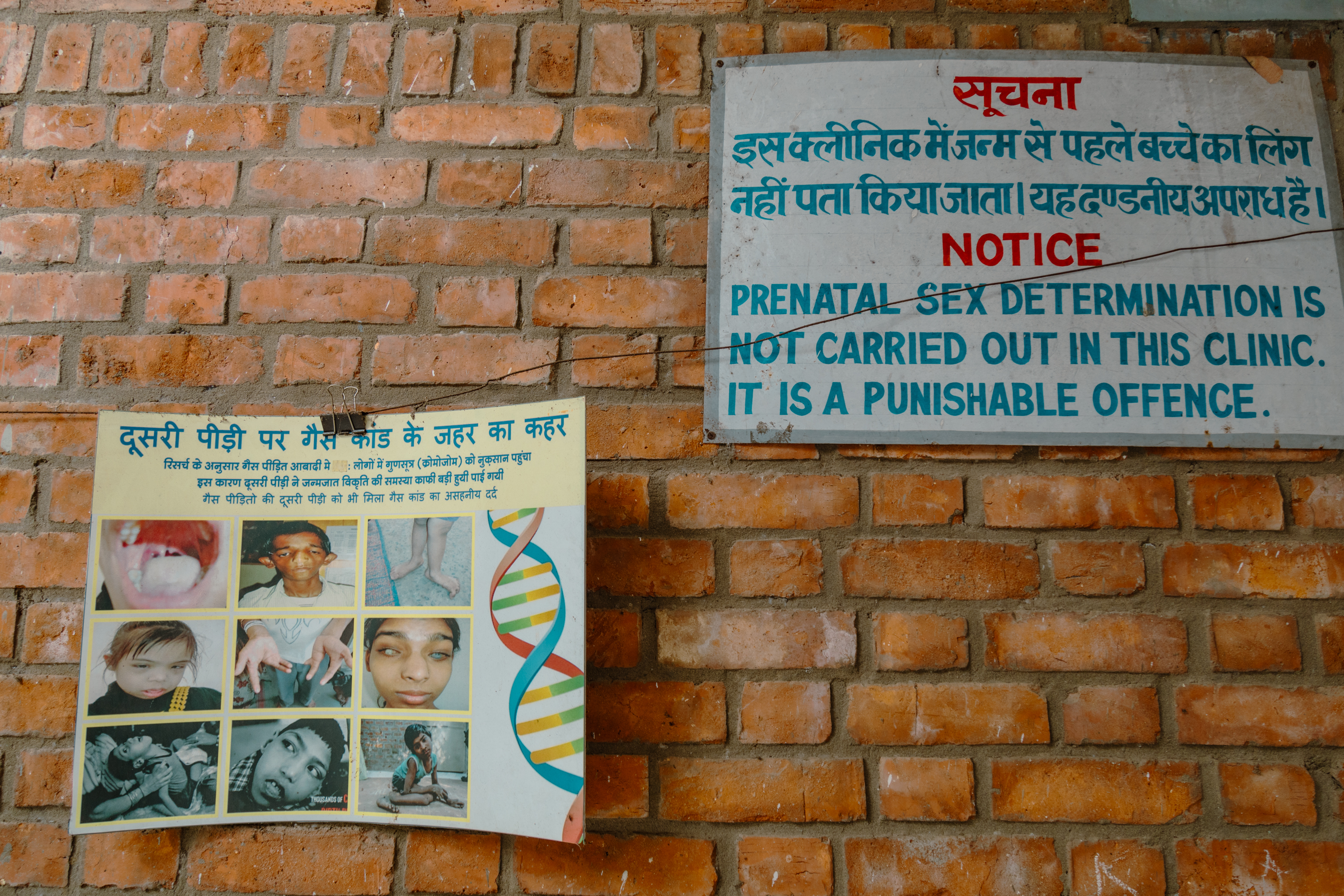

A sign outside of the Sambhavna Trust Clinic in Bhopal. Sex-selective abortion in India is common but illegal. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“Still not a lot is known about the gas and its effects because there has been no systematic research as should have happened. What we know tells us that when people inhale the gas, it enters the lungs, into the bloodstream, and causes damage to different organs. This much we know. The long-term impact is immense,” he explained.

Sarangi continued, “We don’t know the exact composition of the gas. We know Union Carbide did carry out studies of MIC on living systems at the University of Pittsburgh, but the university said UC took whatever they had.”

He believes Union Carbide’s main aim was to get out of any liability that could be attributed to the company, despite knowledge of the terrible impacts of the chemical on humans.

A young mother waits outside of the Chingari Trust center with her son after finishing a rehabilitation session. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“At that time, they claimed gas did not enter the bloodstream and said all the damage that happened was because of direct contact. People got gas in their eyes, so their eyes were scarred and this impacted their vision. They got gas in their lungs, so their lungs got scarred so they got COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. But this does not explain all the impacts that were [later] seen like hypertension and diabetes,” he said.

He thinks the tactic by Dow and Union Carbide has been to suppress any information from coming out. “If a project had the potential to identify the company’s liability, that was likely to be shut down. This became a standard practice so much to just scrap the study. We are finding too many people dying of cancers,” Singari said.

“Many women have cancers and early menopause and the next generation have many irregularities. We expect this to continue. What we don’t know is the impact on the brain, and we have a lot of people with paralysis and don’t know what is happening. There has been no study on the neurological damage people have suffered,” he said.

A physiotherapist works on walking with a young girl with cerebral palsy at the Chingari Trust Bhopal center. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“This is debilitating for a new generation of children in Bhopal, not only from their parents, but from the groundwater. Several of the worst chemicals in the world all exist in Bhopal’s water,” said Nesreen.

“All we are asking is that [the U.S. Department of Justice] serves the summons that are obligated by [the India-US. Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters treaty]. The U.S. is setting bad standards in terms of action against corporate crime,” Singari added.

A doctor works with a child with Down’s Syndrome at the Chingari Trust center in Bhopal, which helps children. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

An Uphill Battle

The question still remains whether Union Carbide and Dow Chemical will ever compensate newer victims of the disaster as demanded by survivors and advocacy groups.

Campaigners and survivors want appropriate compensation for people who have suffered lifelong injuries, for those who have drunk contaminated water, and for the area to be truly cleaned up.

“Everyday, there are new victims being exposed to this poison, there are women who cannot get pregnant, men who cannot become fathers at no fault of their own. The government is only talking about the cleanup at the plant, but the waste outside continues to contaminate more and more people without it being addressed. If the cleanup happens and Bhopal is made safe again, that would be a sense of justice,” Sarangi said.

A view underneath the rusting pipes at the abandoned factory. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“If [Dow] were here, we would tell them to clean up their mess and pay the dues to those who have lost their lives due to your poisons. Here the onus of proof is on us, like we are somehow guilty of some crime and the corporations who did this have gotten away scott free,” said Nesreen.

“This whole compensation process has been the most humiliating because you have to get a lawyer, doctor, etc, to prove you were exposed, but the corporation that did this doesn’t have to prove anything. They should have to prove that my illness is not because of their gas,” she continued. “Would they follow the same standard in their country as they’ve done in Bhopal?”

“The factory hasn’t been dismantled, everyday people are stealing parts off of it. The government wants to build a memorial here. Without cleaning it up, without addressing closure, they want to build a memorial that undermines the environmental disaster which happened here,” said Dhingra.

“We think it’s possible to fix the situation, but the government has to be on our side. There has to be a will to fix this. The stain will always be there, but it can fade away. It’s a blot on democracy, rights, justice. Every anniversary, this theme comes up that nothing has happened. There is a lot that can be done if the corporation and our government is willing to remove the stain,” said Dhingra.

“Future generations will get justice,” vowed Shukla at Chingari Trust. She said she has the energy to continue to fight against the forces and difficulties Bhopalis face.

“Dow should be given a punishment to an extent to show to other companies what will happen to you if you play with the lives of people… This will serve as an example to any other company … they would suffer the consequences. Until justice is served, Dow should not be able to do business here,” she said.

“People who have done it have to be held accountable. Our lives cannot be considered dispensable,” said Nesreen.

“While there are many disappointments, we have not given up on our fight or the hope of justice. That is why after so many years, we have been able to bring a corporation to court,” she ended.

Nesreen, (left), and Sekina (right), hold up a campaign poster. Together they help others in the community who continue to have health effects related to gas exposure and water contamination. Photo by Nicholas Muller.