John MacDougall, a cultural anthropologist from Princeton University in the United States, who dedicated his life to Indonesia and all things Balinese, died on December 30 after a long illness, a sad finale for 2023. He was 53.

Over a career that spanned almost 30 years, MacDougall’s writings and influence would reach the highest ranks of governments struggling to cope with Islamic terrorism across Southeast Asia, which was borne out of 9/11 and the murky ties between al-Qaida and its regional affiliates.

MacDougall arrived in Indonesia in 1988 as a young man with his mother Frances, a Yale-educated nurse who had ties to U.S. diplomacy in Southeast Asia, and his father, John Sr., who was a Princeton academic, also specializing in Indonesia.

A year later he was in Tiananmen Square during the Chinese student protests with journalist Dan Boylan, who he met while studying at Bates College.

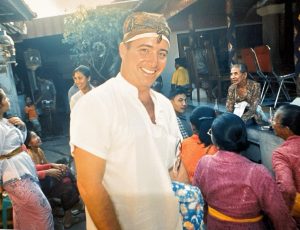

Universally known as Johnny, he learned the many and varied dialects of Balinese and married locally before settling into an idyllic lifestyle raising one child, rollicking in the surf when time allowed. He quickly became a recognized specialist in his own right.

A decade after arriving in Indonesia, he gained international attention through his work as a writer and advisor in East Timor during the convulsions of independence while completing his Masters at Princeton in Social Anthropology at the Institute for Advanced Study with Clifford and Hildred Geertz, America’s most influential anthropologists. His Doctorate was awarded in 2005.

In 2002, he also acted as my translator after Boylan, by then a Fulbright scholar, invited me to contribute to a guest lecture series hosted for Balinese journalists focused on war reporting and Islamic militancy.

We had spent a day in maddening big surf at Legian when the tide was receding but the waves grew taller and steeper. A gnarly rip had sucked us out to sea and I’ll always remember watching as Johnny caught and carved perhaps the biggest wave of the day into the safety of the shoreline.

The same wave pummeled me to the ocean floor but we surfed our way out, held a lecture about potential terrorist attacks that proved telling, and then retired to the Sari Club on the Kuta Strip for my 40th birthday, where Johnny knew all the staff and spoke their languages. They turned on a fantastic evening.

In the same club, a couple of months later, Johnny was looking for survivors, picking through the bones and flesh of the people he knew who had died in the first of the Bali Bombings.

As Johnny once recalled, upon hearing the blasts he raced to the scene and then was “up to his armpits” in body parts. He was in a trance-like state. Time and dangers were forgotten. He just kept digging.

At about 5 a.m. he was exhausted and on the verge of breaking down when he felt a tap on his right shoulder from behind and he heard a voice, with a thick Australian accent, that said: “G’day, can I lend a hand, mate.” A full contingent of rescue personnel had arrived from Darwin.

He never forgot that accent, would always hold a deep affection for Australians, and on rare occasions when he spoke about that dreadful night on October 12 that left 202 people dead, he would shed a tear.

The bombings also left Johnny with an equally dreadful case of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a term that is bandied about all too easily these days. He took the carnage personally, as he should have, and with Boylan and myself was determined to help in finding those responsible.

At times the three of us would work together, from behind closed doors, focusing on Jemaah Islamiyah and its latter-day offshoot Jemaah Anshorut Tauhid as the authorities scored some success. Steadily, one-by-one, the militants were arrested, charged and convicted.

The last, Umar Patek, was paroled a year ago.

Johnny worked for the Carter Center, the International Crisis Group, the World Bank, and Menko Pokhkam, an abbreviation for Indonesia’s coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs. He was also a trusted advisor among the region’s security services.

Many of his written works, which explored topics as wide-ranging as self-identity, emasculation, and conspiracy in post-colonial Indonesia, can be found on the Princeton alumnus site.

In 2010, he returned to the United States with his then wife and child, where he lectured at Princeton University but struggled with PTSD and was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, a disease that took a great toll on his family life.

John MacDougall was an unsung hero from those dark days of Islamic militancy. As Dan Boylan wrote to me: “My God, the surf of Bali almost took us all more than 20 years ago. Now our hearts are filled with sorrow, but minds calm with relief that Johnny’s suffering has finally ended. Johnny was a great and true friend and a fighter for what was right.”

He is survived by his son Angus and his former wife Mona.