Around a week ago, news emerged of the Chinese research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 03 arriving in the Maldives sometime in late January or early February.

China had sought permission from Sri Lanka last year to have the same vessel dock at a Sri Lankan port for replenishment purposes. However, facing strong opposition from India and the United States, Sri Lanka decided in December to enforce a comprehensive one-year ban on all foreign maritime research vessels.

Sri Lankan policymakers, opinion leaders, and academics frequently overstate the country’s significance to China, despite numerous instances showcasing China’s pragmatic approach of not concentrating all its interests in a single entity. By turning to the Maldives to dock its vessel, China underscored yet again its diversified strategic outlook.

Conversely, the decision to prohibit all foreign research vessels poses a significant setback for Sri Lanka’s marine science research. This unilateral decision by the Sri Lankan government – made without engaging universities, research institutions, or other experts – not only renders marine research unfeasible, but also hinders local researchers and graduates from acquiring valuable experience in an international research setting with access to cutting-edge technologies.

Furthermore, it exacerbates the challenge of brain drain, pushing more researchers to seek opportunities abroad, and adding to the country’s existing struggles.

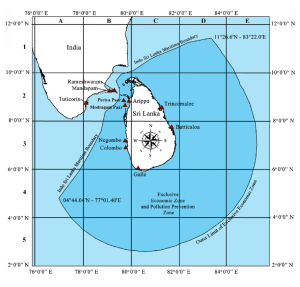

Sri Lanka is strategically located in the Indian Ocean, just a few kilometers south of India. The Sri Lankan coastline is over 1,300 kilometers and its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) spans over 500,000 square kilometers. The EEZ is almost eight times larger than the country’s landmass. Sri Lanka has the rights to the resources in the water column, seabed, and subsurface of the EEZ. The underwater resources in its EEZ remain unexplored and untapped.

Despite being strategically positioned and boasting extensive territorial waters, Sri Lanka has made limited efforts to explore its maritime expanse.

Successive Sri Lankan governments have shown remarkable blindness to the potential of the country’s EEZ. Its universities hardly pay attention to marine research and the few universities that offer degrees in marine sciences are underfunded.

Given Sri Lanka’s lack of adequate naval assets for comprehensive oceanic scanning, fostering collaboration with foreign nations becomes crucial in unlocking the potential of the country’s abundant maritime resources and enhancing the development of the blue economy.

As noted above, collaborating with foreign partners equipped with advanced technologies is essential for researchers and universities in the country. Moreover, Sri Lanka faces a shortage of both raw and processed data, which plays a pivotal role in understanding weather patterns, particularly for optimizing agricultural activities. Despite consistent promises to harness the advantages of a blue economy, the government’s financial backing for ocean research initiatives has remained constrained.

This has compelled universities to depend on foreign assistance. Universities do not have the data sets of previous research conducted with foreign nations. A considerable number of skilled scientists have departed the country, with their invaluable insights.

To make matters worse, the power struggle between China and the United States and its allies in the Indian Ocean has made marine research highly political. The arrival of the Chinese research vessel Yuan Wang 5 in Sri Lanka in August 2022 triggered a media frenzy, and the term Chinese “spy ship” has entered common parlance in South Asia.

The Sri Lankan foreign policy establishment’s response to the media frenzy and increasing pressure from India and the U.S. against allowing Chinese research vessels to dock at the island has been unsatisfactory.

The government has not managed to satisfy India or the United States, even as it has undermined the country’s relationship with China. Now Colombo has kneecapped Sri Lankan research.

In the last two years, sections of the media have hounded and demonized researchers at Ruhuna University and the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA) for being involved with Chinese researchers. This has resulted in Ruhuna University deciding not to get involved with a Chinese research vessel last year. The government has also allocated virtually nothing to boost marine research facilities as well.

Now, with China gaining access to the Maldives for supplying and replenishing its research vessels, it holds strategic leverage that could make Sri Lanka’s situation more difficult. For instance, China could slow down bilateral debt restructuring, crucial for accessing further tranches of IMF financing that Sri Lanka urgently needs. Sri Lanka is not winning friends and influencing people.

Moving forward, Sri Lanka must reconsider its approach to marine research, recognizing the importance of collaboration with foreign partners and the potential benefits that such ventures can bring. A balanced foreign policy that safeguards national interests while fostering international scientific cooperation is crucial. Additionally, increased domestic investment in marine research facilities and academic programs can help retain and attract talent, ensuring the country does not fall further behind in understanding and harnessing its marine potential.

Ultimately, a strategic and collaborative approach is imperative for Sri Lanka to navigate the complexities of the evolving maritime landscape and unlock the full spectrum of opportunities presented by its extensive territorial waters and EEZ.