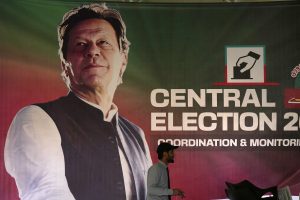

On February 8, Pakistanis voted in elections to the National Assembly and four provincial assemblies. The elections were controversial. In addition to relentless efforts by the Pakistan establishment to weaken Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in the months preceding polling, the vote was manipulated to favor the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Yet it was the PTI – technically, PTI politicians running as independent candidates – that emerged with the most seats.

The PML-N and PPP are in talks to form a coalition government. What does a weak coalition government with the military pulling the strings mean for Pakistan’s political stability? Will the new prime minister engage in talks with India?

Pakistani political and security affairs expert Aqil Shah, who is the author of “The Army and Democracy: Military Politics in Pakistan” (Harvard University Press, 2014), throws light on these and other questions. In an interview with The Diplomat’s South Asia editor Sudha Ramachandran, Shah pointed out that “even if the PTI’s success has thrown a spanner in the works, the generals can still ensure a favorable outcome through the application of time-tested divide and rule tactics buttressed by sticks and carrots.”

“The military,” he said, “will rule without governing.”

A post that has gone viral on social media is “the Pakistani military has never lost an election and never won a war.” Has that changed with the recent election?

I think this observation is not far from the truth in general. However, the army has lost elections in the sense of misreading electoral dynamics and the depth of public sentiment against its illegitimate meddling in politics (e.g., the 1970 elections in which the Bengali nationalist Awami League won a landslide victory in erstwhile East Pakistan). No matter how hard it tries to influence elections, it cannot always determine outcomes ex-ante because of the uncertainty over voter preferences.

On the surface, the unexpected victory of PTI-affiliated candidates seems like a jolt to the military. But another way of looking at it is that the elections were inconclusive, a draw of sorts as they produced no clear winner. The Pakistan Tehreek-e Insaf (PTI) did secure the highest number of National Assembly seats (92) but fell short of getting the simple majority needed to form the federal government on its own. The party widely believed to enjoy the military’s blessing, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) scored 75 and 54 seats respectively. Split mandates produce coalitions, which are relatively easier to make or break than a single-party majority government. Even if the PTI’s success has thrown a spanner in the works, the generals can still ensure a favorable outcome through the application of time-tested divide and rule tactics buttressed by sticks and carrots.

What form is the Pakistan military’s intervention in politics likely to take in the coming weeks and months?

The Pakistan military’s main goal has always been to safeguard and advance its institutional interests when it faces any form of civilian political defiance or resistance. Right now, the generals want to keep Imran Khan’s party, the PTI, out of power. Mission “get Khan” was set in motion after he developed irreconcilable differences with then-Army Chief of Staff General Qamar Bajwa over the appointment of the head of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Ultimately, the military backed the PML-N-led opposition, the Pakistan Democratic Movement’s (PDM) vote of no-confidence that ousted Khan from office in April 2022. The PDM subsequently formed a coalition government, which was replaced by the military-backed caretaker regime in August 2023.

The generals would like to install a PDM 2.0 coalition, which will likely be led again by former Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif (2022-23), who is known for his conciliatory approach towards the military. That contrasts with his older brother, former PM Nawaz Sharif’s particularly troubled relationship with the generals. To achieve this objective, the ISI has been working overtime to strike an agreement between the PML-N and the PPP. Despite an initial agreement to form a coalition, the negotiations have stalled over “who gets what.” And even if the politicians resolve the impasse, widespread allegations of electoral rigging would dent the legitimacy of any coalition.

To what do you attribute the remarkable electoral performance of the PTI-backed independents? Support for Imran Khan? Voter anger with the military establishment’s determined bid to manipulate the elections? Or something else?

I think it appears to be a vote against the army’s repression of the PTI and its not-so-deniable hand in the pre-poll manipulation of the vote. The army has used the May 9, 2023 attacks on its installations that were led by Khan’s supporters, protesting his arrest, to methodically dismantle the party, for example, by jailing and harassing its leaders, who were forced to dump Khan and, in some cases, even made to foreswear electoral politics on live television.

Khan has a cultish hold over his followers, who believe he is a modern-day messiah above all reproach. When he fell out with the army, Khan mobilized boisterous rallies of his supporters in which he blasted General Bajwa for colluding with the opposition (and the U.S.) to replace him. Ultimately, the army had Khan convicted and incarcerated on politically motivated charges, including allegations of corruption, a supposedly fraudulent marriage, and for violating the Official Secrets Act by publicizing the contents of a secret diplomatic cable to prove that his ouster was the result of Washington’s “regime change” agenda.

The army’s unfair treatment of their “great leader” may have been the last straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s stripping the PTI of its election symbol (cricket bat) before the election, which basically eliminated the party from the electoral arena, and forced its leaders to contest the elections as “independents,” added further fuel to the fire. While the overall voter turnout was low, all this resentment, assiduously amplified by the party’s innovative use of social media in its election campaign, cemented the PTI voters’ determination to exercise “voice” through the ballot.

Supporters of imprisoned Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s party chant slogans during a protest against the delaying result of parliamentary election by Pakistan Election Commission, in Karachi, Pakistan, Feb. 11, 2024. AP Photo by Fareed Khan.

What are the implications of the election results for the political crisis in Pakistan, civil-military relations, and democracy?

The contested election results are likely to deepen Pakistan’s persistent political instability, which is primarily a result of the military’s domineering political influence and repeated interventions in the domestic affairs of the country. While Khan is no democrat, you could still see the vote as a peaceful political expression of frustration and anger at the generals, which could be interpreted as a small victory for Pakistan’s democratic future. However, Khan’s opposition to the military is not a result of his commitment to civilian supremacy (Khan is not unique in his opportunism) and is instead driven by his hurt pride and hunger for power.

A coup may not be imminent, but it is fair to say that Pakistan is unlikely to come out of its enduring praetorian trap (marked by a bewildering cycle of coups, military governments, civilian rule, and so on). The country’s assertive military will retain its vast array of prerogatives in the state, national security and the economy and keep its boots on the neck of Pakistan’s already enfeebled civilian institutions, including the political parties and the parliament, to maintain control. The result will likely be another hybrid regime in which the military’s de facto power overrides an elected (or army “selected”) government’s de jure authority. In other words, the military will rule without governing.

Islamist parties have not performed well despite the growing Islamization of Pakistan. What does it say about Pakistani voters?

Islamist parties have never garnered more than 12 percent of the popular vote in Pakistan in any election since 1970. In most elections, the electoral performance of the religious parties has been dismal. To understand this pattern, we need to make a distinction between political Islam and the beliefs and practices of lived Islam in the country, which exhibits surprising diversity. It will not be unreasonable to claim that while Pakistani society is religiously conservative, the majority of Pakistanis are not in favor of an explicitly theocratic state.

While Pakistan officially claims to be an Islamic republic, the Islamization of laws and policies is traceable to the military dictatorship of General Zia-ul Haq (1977-1988), who cynically instrumentalized Islam to gain legitimacy. The state-sanctioned version of Islam, including the notorious blasphemy laws, has produced extremely violent streaks in society, evident, for example, in vigilante lynching of individuals accused of blasphemy, which often turns into mob violence against religious minorities, particularly Christians.

As far as the electoral performance of religious parties is concerned, there is variation in voting patterns across the four provinces. However, no Islamist party has managed to create a country-wide support base. The Jamaat-e-Islami (JI)’s support has traditionally been restricted to the Urdu-speaking middle classes in urban Sindh, particularly Karachi, and even there, it has long faced a potent challenge from the MQM (Muhajir Qaumi Movement) that has all too often wiped out its electoral fortunes. The vote bank of the Deobandi Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Pakistan-Fazl (JUI-F), the country’s leading Islamist party, led by Maulana Fazlur Rehman, is localized in southern parts of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. But other non-Islamist parties have frequently managed to beat back the mullahs in their stronghold, like the PTI did in this election.

In general, Pakistani voters do not see much utility in voting for parties that instrumentalize Islam for political gain and have a low likelihood of success in the first place. In addition, the right of center conservative parties like the PML-N or the PTI are fully capable of cladding themselves in Islamic garb to take the sting out of the Islamist parties’ claim of exclusively representing religion in politics.

The Islamist parties do have nuisance value, but their power usually does not flow from the ballot, but the bayonet. It is the mutually beneficial dalliance of Islamist parties like the JI and the JUI-F (albeit punctuated by moments of opposition) and the Pakistani military/ISI, combined with their ability to freely mobilize their motivated cadres, that endow them with street power that the military can use to pressure elected governments that fall out with the generals.

The Pakistani military’s prestige has been undermined. The new coalition government is weak and lacks legitimacy. What does this mean for India-Pakistan relations?

India-Pakistan relations have always been the exclusive domain of the army. Whenever civilian leaders (e.g., Nawaz Sharif) have tried to find a way to normalize relations with India, the army has retaliated with a vengeance. Take, for example, the 1999 Kargil operation, which the generals clandestinely launched without the full knowledge of Sharif’s elected government. The ensuing border war with India sabotaged the incipient Lahore peace process between the two sides. The military ultimately ousted Sharif in a coup and justified it, to paraphrase then-Chief of Army Staff General Pervez Musharraf, at least in part because he had “sold out” Kashmir to India.

In any case, the new coalition government will be faced with severe domestic challenges, including the economic crisis. Hence, an outreach to India would likely be low on its radar, and even if it was interested in seeking a rapprochement, say by opening up trade, it will require a green signal from the army.