China’s activities in the security and defense sector in Latin America and the Caribbean are a small but strategically significant portion of its engagement with the region. Beijing has openly acknowledged its interest in engaging with the region on security matters in the 2008 and 2016 China-Latin America Policy White Papers, as well as in the 2022-2024 China-CELAC plan. That interest is also reflected in the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs white paper elaborating on China’s Global Security initiative.

The security dimension of China’s engagement in the region has been highlighted by the head of U.S. Southern Command and other senior U.S. defense officials, as well as receiving occasional coverage in the media and academic works, generally with a focus on the threat posed to the United States. I want to complement those writings by providing a brief overview for a general audience of the characteristics and trends in China’s security engagement in the region, and how it is evolving, focusing on seven major trends:

- Arms sales to anti-U.S. populist states

- The use of gifts to develop security relationships

- Procurement and quality difficulties

- Setbacks in China’s arms sales to democratic states

- Increasingly persistent Chinese military presence in Latin America

- Expanding activities by China-based private security companies in Latin America

- Increasing training of Latin American security personnel in China

China’s Arms Sales Focus on Anti-U.S. Populist States.

To date, the principal purchasers of Chinese military equipment in Latin America have been anti-U.S. populist regimes, including Venezuela (under Hugo Chavez and Nicholas Maduro), Bolivia (under Evo Morales), and Ecuador (under Raffael Correa).

Venezuela’s purchases from China include 25 Hongdu K-8W fighter aircraft (18 in 2008 and seven more in 2010), as well as military radars. They also include Chinese armored vehicles such as the VN-4 purchased for the Venezuelan Naval Infantry beginning in 2012, and ZBL-09 armored personnel carriers, as well as Chinese riot control vehicles, purchased for the Bolivarian National Guard beginning in 2013. China has also sold Venezuela C-802 anti-ship missiles (beginning in 2020), DJI Mavic Air unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) (since 2014), and at least 215 SAIC/IVECO military ambulances, among other items.

With respect to Bolivia, China sold the Morales regime six K-8W fighters, six H-425 military helicopters, and 31 armored vehicles, as well as donated a number of dual use vehicles and equipment over the years.

China sold the regime of Rafael Correa in Ecuador 709 military trucks, a CETC radar system, and 10,000 assault rifles, albeit with substantial problems, as discussed later.

China has had some success in military sales to less anti-U.S. regimes, including providing four WMZ551 Armored Personnel Carriers to Argentina, at least 27 Type 90B multiple-launch rocket system vehicles to Peru, and an Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) to Trinidad and Tobago in 2014.

Chinese military-affiliated industries have also had some success selling non-military goods to governments in the region. In 2012, for example, the Brazilian Navy contracted China’s Guangzhou Hantong to build an oceanographic ship. It was delivered in 2015.

China’s Use of Gifts to Develop Security Relationships

China has regularly donated vehicles and equipment to Latin American military and police forces as part of its efforts to curry goodwill and build relationships.

China donated five 8×8 armored vehicles and a self-propelled bridge to Peru. In November 2022, it offered to provide an additional three ZBL-08E 8x8s, as well as 46 support vehicles, including 16 SUVs, 18 King Long buses, 12 ambulances, and three firefighting vehicles.

China has similarly donated equipment to Bolivia, Colombia (including self-propelled bridges), and the Jamaican, Dominican Republic, and Guyanese Defense Forces.

Such donations often concentrate on dual use vehicles and engineering equipment, rather than weapon systems, per se. They have also included military transport aircraft, such as the gifting of Harbin Y-12 military transport aircraft to Guyana, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

China’s donations of security equipment to the region have focused on police forces, with whom Chinese engagement may appear less strategically challenging. However, the sheer needs of the beneficiaries magnify the goodwill purchased by the Chinese investment. Major examples include China’s donation of 140 motorcycles and eight ATVs to the Dominican Republic police and military in December 2020, on top of fire trucks donated in 2018, and 30 ambulances given in July 2022.

In Costa Rica, China donated a $16.5 million police training facility, followed by 350 police vehicles, and at least $10.5 million in equipment ($5 million in 2017 and $5.5 million in 2018). In 2021, China further gave Costa Rica 100 motorcycles, as well as 2,000 helmets and Kevlar vests.

In Panama, in 2023, China donated 6,000 in Kevlar vests and protective helmets worth $4 million to the national police, air and naval service (SENAN) and border control service (SENAFRONT).

Procurement and Quality Difficulties

Latin American countries across the political spectrum have had significant difficulties with their arms purchases and gifts from China. At least four of the K-8W fighters Venezuela purchased from China had crashed by 2022, with some problems attributed to errors arising from poorly translated Chinese technical manuals. In Bolivia, two of the six Chinese K-8Ws have similarly crashed.

In Ecuador, problems with the performance of the radars led the China-sympathetic government of Rafael Correa to return them, ultimately devolving into a protracted legal dispute.

Both Argentina and Peru have had difficulties with poor quality of Chinese munitions, leading to the jamming of guns and the endangering of personnel firing them, particularly in combat situations.

Military trucks given to Peru by China had problems violently shaking at road speeds. The effects were reportedly so severe that the Peruvian military wanted to return the donated vehicles. A Y-12 transport aircraft donated to Colombia had to be taken out of service after flying through inclement weather rendered it unairworthy.

In the case of both Peru’s purchase of the Chinese Type-90B MLRS, and Bolivia’s purchase of the H-425 helicopters, suspicion of corruption in the acquisition contract, including inflation of the purchase price, led to investigations by the governments buying the equipment.

Setbacks in China’s Arms Sales to Democratic States

Although China continues to pursue arms sales in the region, including regular engagement with Latin American defense organizations, participation in military trade shows, and the previously noted use of gifts, among other techniques, it has experienced an increasing number of setbacks in those efforts, particularly among democratic states.

In Argentina, in 2023, the outgoing China-sympathetic Peronist government of Alberto Fernandez decided to purchase U.S.-made Danish F-16 fighter aircraft, instead of Chinese JF-17s. The latter would have been the most sophisticated Chinese aircraft sold to the region to date. The rejection of China’s offer came on top of an Argentine decision not to pursue a Chinese armored vehicle to replace problematic WMC-551s from China, and the prior government’s purchase of a French patrol boat instead of a Chinese one being considered.

Also in June 2023, the center-right Uruguayan government of Luis Lacalle Pou decided to withdraw from the purchase of Chinese offshore patrol vessels for “geopolitical” reasons,” although China had twice lowered the price in an effort to save the deal. A supporting 2017 China-Uruguay defense agreement was blocked in June 2022 by the Uruguayan parliament.

In Brazil, participation by China-based vendors in a bid for Brazil’s future frigate program and its surveillance architecture Sisgaaz have not advanced.

Increasingly Persistent Chinese Military Presence in Latin America

Since at least 2019, China has had personnel at the electronic intelligence-gathering facility in Lourdes, Cuba. It has reportedly also been negotiating an agreement to train Cuban military personnel on the island on an ongoing basis. Such activities suggest increased Chinese willingness to risk provoking the United States by establishing a low-level ongoing presence close to the U.S. mainland.

The growing Chinese military presence in the region also includes periodic deployments by its hospital ship, Peace Ark, to the region (in 2011, 2015 and 2018-2019); the visit of two Chinese missile frigates to Chile, Argentina, and Brazil in 2013; and a port call by a Chinese military ship to Havana, Cuba in 2016. Between 100-200 Chinese military police were present in the Brazil-led MINUSTAH Peacekeeping mission in Haiti from 2004-2012.

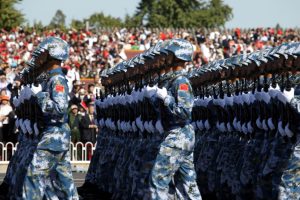

Chinese military delegations periodically come to the region. In June 2023, the Political Commissar of the Chinese navy, Fleet Admiral Yuan Huazhi, visited the leadership of the Brazilian Navy. In August 2022, a delegation from China participated in a military sharpshooting exercise hosted by Venezuela. In 2023, as well as in prior years, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) sent uniformed members to participate in Mexico’s Independence Day Parade.

The PLA, in principle, has a position as an observer at the Inter-American Defense Board and Inter-American Defense College in Washington DC, although it has not regularly sent persons there in recent years.

The PLA has also regularly sent military delegations to visit Latin American military institutions. In recent years, they have visited and even attended key Latin American training schools, including Colombia’s Lanceros special forces school in Tolemaida, Brazil’s Jungle Warfare School in Manaus, and the latter’s well-respected peacekeeping school, CCOPAB.

PLA representatives are further beginning to be included at forums in the region in which the United States is present. In November 2023, for example, the head of the PLA Naval Infantry, Zhu Chuansheng, attended the Fourth Naval Infantry symposium in Rio de Janeiro, alongside his U.S. counterpart, Marine Corps General David Bellom, as well as senior military leaders from Portugal, Argentina, Colombia, South Korea, and France.

Expanding Activities by China-Based Private Security Companies in Latin America

As China-based firms expand their operations in dangerous parts of the region, Chinese private security companies (PSCs) are increasingly following them there (albeit not yet to the same degree as in Asia or Africa).

In Peru, China Security Technology Group provides security services in the mining sector. In Argentina, Beijing Dujie Security Technology Company has an office in Buenos Aires. In Panama, China’s Tie Shen Bao Biao advertises personnel protection services. The PRC-based security company Zhong Bao Hua An represents itself as having business in Panama, El Salvador and Costa Rica. In Mexico, the “Mexico-Chinese Security Council,” created in 2012 by former Chinese government official Feng Chengkang, represents itself as protecting Chinese business personnel from gang violence.

Increasing Training of Latin American Security Personnel in China

Latin American military personnel have long traveled to China to participate in courses at China’s National Defense University in Beijing, as well as other professional military education programs. They have also served in China as defense attaches and in other capacities.

Such activities are gradually broadening. In July 2023, for example, Dominican Republic Defense Minister Carlos Diaz Morfa authorized Dominican personnel would participate in a military sniper competition in Xinjiang.

Beyond traditional military engagement, the Chinese government is expanding opportunities for Latin American law enforcement personnel to visit China. In September 2023, for example, China hosted the “Global Public Security Cooperation Forum” in Lianyungang, which was attended by senior police leaders of Suriname and Nicaragua. There, Nicaraguan Police Chief Francisco Diaz reportedly discussed training of Nicaraguan police personnel in China. Similarly, in July 2023, Dominican leaders reportedly negotiated training for Dominican police officials in China.

Implications and Conclusions

Two decades of China’s security engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean has already borne fruit in terms of knowledge of the region, and in the relationships the PLA has built with its security sector counterparts. Peru’s recent Interior Minister Vicente Romero Fernandez, for example, had attended a professional military education school in China, while its former Minister of Defense George Chavez Cresta served there as military attaché. Similarly, the commander of Uruguay’s Army, General Mario Stefenazzi, was that country’s military attaché in China.

Expanding China’s security engagement in Latin America and the Caribbean supports Beijing’s relationships with, and influence over, partners there, including improved ability to protect China-based companies operating in the region. Even more importantly, in the event of a war between China and the United States, PLA relationships with Latin American defense personnel and familiarity with its strategic geography from operating there improves the speed and effectiveness with which the PLA can launch military operations in the region, from small-scale intelligence and special forces operations to the projection of military force against the United States and its allies from facilities in the region.

While security engagement is the right of sovereign countries, the equally sovereign United States has the right to consider how China’s expanding security engagement could affect its strategic equities in the region, and conduct a respectful, if frank, dialogue with its neighbors on the subject.