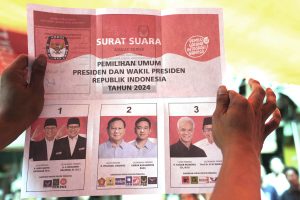

Indonesians went to the polls on February 14 to elect a new president and vice president, with some 204 million of the country’s 270 million population registered to vote.

Ahead of the election, which was the single largest one-day election of its kind in the world, there had been some fears that polling stations could be the targets of terrorist attacks, although these fortunately proved to be unfounded.

Not only did terrorists fail to disrupt the “festival of democracy,” as the election was dubbed across the country, but some former members of hardline groups even went to the polls themselves to cast their votes –some of them for the first time.

In East Java, convicted Bali bomber, 57-year-old Umar Patek, cast his vote alongside his wife. Patek was convicted of mixing some of the chemicals to make the bombs that killed 202 people in Bali in 2002 and injured another 200, and was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2011 before being released on parole in December 2022.

Patek proudly told The Diplomat that both he and his wife were first-time voters in the election, which is not particularly surprising, as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), the hardline Islamist group behind the Bali bombing, has traditionally shunned and refused to recognize the Indonesian state.

JI, which is classified as a terrorist organization in Indonesia, has long followed an ideology that preaches the destruction of the Indonesian state and the establishment of a caliphate in the world’s most populous Muslim nation, and regularly attacked police stations and army posts during its heyday in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Any form of government organization or political apparatus, including democratic elections, has long been outlawed for members of JI, which makes Patek’s decision to vote (which is not mandatory in Indonesia) even more interesting and perhaps persuasive in terms of Indonesia’s strides in tackling radicalization in recent years.

And Patek was not the only one to make his way to the ballot box.

In the city of Surakarta in Central Java, which is also known as Solo, Abdul Rohim Bashir, the son of Abu Bakar Bashir, the so-called “spiritual godfather” of JI, told The Diplomat that both men also cast their votes, getting up early to get to the polls first thing in the morning on February 14.

Abu Bakar Bashir, who co-founded JI with Abdullah Sungkar in 1993, was released from prison in 2021 after serving two-thirds of a 15-year prison sentence for terrorism-related charges that were not linked to the Bali bombing, and also publicly threw his support behind presidential candidate Anies Baswedan before the election – something that would have been unthinkable 20 years ago.

When the Bali bombing took place, Indonesia did not have robust anti-terrorism legislation, which was only drafted in 2003 and applied retroactively, and did not have deradicalization programs across the country.

However, in the years that followed the Bali bombing, and in the wake of other attacks such as the 2003 attack on the JW Marriott in Jakarta that killed 11 people, the Indonesian authorities worked with other countries, including Australia and the United States, to create deradicalization programs for those convicted of terrorism-related offenses which have widely been praised for being largely successful and for significantly reducing attacks across Indonesia.

While the “success” of deradicalization can be difficult to measure, the last JI attack was in 2011 when a police station in Cirebon was bombed, with the suicide bomber being the only casualty, and the Indonesian authorities do appear to have snuffed out the large scale attacks of the 2000s.

In Jakarta, Ali Imron, who was sentenced to life in prison for his role in orchestrating the 2002 Bali bombing, told The Diplomat that he had planned to vote for presidential candidate Ganjar Pranowo, and that he had participated in voting in previous presidential elections from prison where he is incarcerated at the Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Police Headquarters.

This year, however, Imron said that he had been unable to cast his vote due to a shortage of ballot papers.

Far from the days when he would have refused to participate in such a nationalistic spectacle, Imron expressed some frustration regarding the situation, saying that he had been looking forward to casting his vote.

Rather than refusing to participate in civil society, it seems that some of the most senior members of JI are embracing their rights and reintegrating into society, one of the cornerstones of Indonesia’s deradicalization programs. The programs also stipulate other activities in order to receive remission time such as attending flag-raising ceremonies for Indonesia’s national day on August 17 and swearing an oath to the Indonesian state.

Whether the Indonesian authorities have managed to completely rid the country of terrorist cells is a separate matter for debate, but the lack of attacks on the election and the flurry of former JI members eager to turn up at the polling stations suggests that they have at least managed to change some of the pre-conceived notions held by once radical extremists.

To many people, turning up at a polling station to exercise one’s right to vote mostly evokes feelings of democratic freedom, but to others, it comes laden with deep and radical connotations of state control.

If framed as part of the work of deradicalization, of which Indonesia has always been at the forefront, former terrorists happily handing in their ballot papers is not to be underestimated.