The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. Kenneth Dekleva – professor of Psychiatry and director of Psychiatry-Medicine Integration at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas; senior fellow at the George H.W. Bush Foundation for US-China Relations; and previously regional medical officer/psychiatrist with the U.S. Dept. of State from 2002-2016 – is the 403rd in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.” The views expressed in this interview are entirely his own and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, the U.S. Department of State, or UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Compare and contrast Xi Jinping’s past and present leadership psychology.

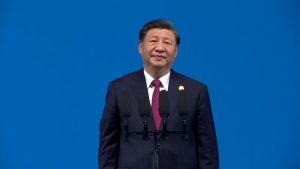

Xi Jinping has been president of China for over a decade, and as one of the most powerful leaders in the world today, his decisions have profound consequences for economic security, stability, and world peace. An understanding of Xi’s leadership psychology is critical in understanding his response to crises, his negotiating style, and how he can be expected to meet China’s economic and political challenges over the next decade.

Xi is rational, ruthless, and resilient. He is a formidable adversary and is often underestimated, including by various components of the U.S. intelligence community, who have in his case often confused status and ideological biases with ability. His successes embody his ability to wed his remarkable personal narrative with that of aspirational objectives for China, such as the Chinese Dream of Great Rejuvenation, drawing upon a combination of Chinese nationalist and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) themes.

Diplomats, business leaders, and dignitaries who have met with Xi have described him as polite, restrained, and a good listener. The comments of giants such as the late Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and the late U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger are instructive. Lee, who had met every previous Chinese leader, including Mao, stated, “I would put him in Nelson Mandela’s class of persons. A person with enormous emotional stability who does not allow his personal misfortunes to affect his judgment. In other words, he is impressive.” In July 2011, Kissinger described Xi as “more assertive, there is a significant presence when he enters a room. His generation has been steeled by suffering.”

Identify Xi’s decision-making blind spots.

Xi is a true believer, believing in the CCP’s primacy, and in China’s potential for greatness and rejuvenation. Xi has repeatedly stated that “the East is rising, and the West is in decline.” Xi’s exceptionalism, while linked to his personal and political self-confidence, represents a potential blind spot.

Having visited America on numerous occasions since 1985, Xi has to appreciate America’s exceptionalism and greatness. But Xi likely misses America’s resilience, a different part of its exceptionalism. It’s an easy mistake, when America remains politically, socially, and economically divided, inward-facing, and weary after two decades of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Had Xi visited America in 1979, he would have seen a country equally beset by – in President Carter’s words – “malaise,” stagflation, and political/military decline. But the election of President Reagan changed all that. Xi ignores such facts at his peril.

And as Xi ages into a third (and possibly a fourth) five-year term, the risk exists that he will, like many aging, autocratic leaders, exhibit a larger degree of cognitive rigidity in his decision-making.

Xi, beholden to Marxist dialectical reasoning, is seen as rigid and ideological – an easy bias to see. But doing so misses Xi’s pragmatism. Xi’s shift in course after COVID lockdowns and his recent appeals to the private sector, as China struggles with rising youth unemployment, high levels of debt, and sluggish growth, highlight his flexibility. Diplomatically, Xi has recently shifted his language, course, and tone in reducing tensions with America, where relations had fallen to new lows. This was dramatically seen in his November 2023 speech – which received a standing ovation – to hundreds of American business executives in San Francisco.

In uncertain areas such as economic slowdowns, response to COVID, foreign relations, trade, crises (e.g., the spy balloon incident of 2023), and China’s role in diplomacy involving Russia, North Korea, Ukraine, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, Xi has navigated more cautiously, even patiently, while shifting tactics to align his and China’s national interests within the ancient Chinese paradigm of shi, outlined by Professor David Shin as “the alignment of forces, the propensity of things, or the potential born of disposition.”

Examine Xi Jinping’s leadership interactions and dynamics with global leaders.

Xi has met with Russia’s President Putin 42 times since coming to power in 2012. Xi has spoken of their closeness, referring to him as a “dear friend,” and highlighting their “deepening trust” and a “deep friendship.” During the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, both leaders cited their “no limits friendship.” Many external observers have read more deeply into this friendship than it warrants. I’d suggest that it’s more uneven and unequal, where Xi (and China) is the stronger of the two partners.

Xi’s relationship with North Korea’s Chairman Kim Jong Un is also intriguing. While China and North Korea have been – in the words of Mao – “as close as lips and teeth” – this has not always been the case since Xi came to power. He and Kim only first met during 2018 and 2019, before and after Kim’s historic Singapore summit with President Trump. Both visuals and readouts of their meetings hinted at a growing closeness, but for both, a pragmatic one, as China needs a politically stable North Korea as a strategic buffer vis-à-vis South Korea, and North Korea is deeply reliant on China economically.

Xi’s self-confidence comes across most notably in his interactions with many other foreign leaders, choosing when to meet, whom to meet, and how to meet with them, in the service of his and China’s national interests. This has emerged in his interactions with leaders at the 2022 SCO Summit, the 2022 BRICS Summit, and his recent meetings with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Council President Charles Michel, Germany’s Olaf Scholz, France’s Emmanuel Macron, and numerous American business and political dignitaries, including the late Henry Kissinger, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen, Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo, Governor of California Gavin Newsom, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Analyze Xi Jinping’s calculus toward China’s approach to Taiwan.

Will Xi invade Taiwan? Xi has repeatedly stated that reunification will occur, peacefully or otherwise, and yet he – not a disruptor per se – is unlikely to make an impulsive or irrational decision to invade Taiwan. If a red line were crossed, and Taiwan declared independence, Xi could be forced to act militarily, as well as diplomatically, economically, and politically.

A possible scenario involves China further isolating Taiwan, using a whole gamut of government approaches, including air defense patrols, naval blockades, espionage, China Coast Guard patrols, cyberattacks, political/economic pressure, diplomatic pressure, and legal measures. Russia’s war setbacks in Ukraine may have chastened Xi, but Ukraine’s failed counteroffensive and loss of fiscal year 2024 U.S. congressional funding due to U.S. domestic political changes may further embolden Xi.

Assess how Xi’s leadership style could define China’s future direction.

Xi remains a confident, powerful leader, who has achieved immense successes, including continuing to lift hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty, a significant achievement and component of Xi’s Dream of Chinese Great Rejuvenation. During his February 2023 visit to Moscow, in parting with President Putin, Xi stated that global power dynamics are shifting, in an evolving multipolar world, and that “together we should push forward changes that have not happened for 100 years.” Xi’s response to such challenges will define both his and China’s legacy during the 21st century.

Understanding Xi’s leadership style, political psychology, and governance outcomes is critical as a rising China asserts itself in Asia, the Global South, and the Middle East, and increasingly counters America’s stature, influence, and global power.