If you or someone you know is having thoughts of self-harm, please seek help immediately. You can find resources in India here or search for helplines in other countries here.

“All India Rank,” a Hindi film that was recently released in India, has been garnering rave reviews. It authentically depicts the trauma of a 17-year-old boy sent off to India’s “coaching capital” Kota in Rajasthan to prepare for admission to the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

The pressure of gaining entry into these reputed engineering institutes by clearing the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) or into medical colleges through the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET) has been driving an increasing number of teenagers to suicide.

In these past two months alone, six students in Kota have died by suicide. Last year saw an all-time high of 26 students in the town kill themselves.

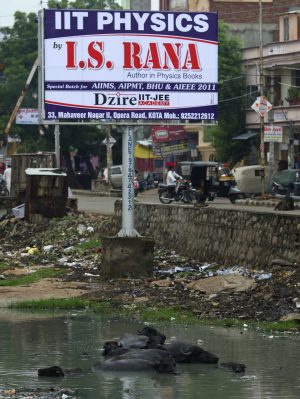

The suicides in Kota point to a larger crisis in India’s higher education sector where careers in engineering and medicine are highly coveted and perceived as the means or a ticket to a better life. No wonder then that 250,000 students from across the country flock to Kota for training in its 300 or more coaching institutes.

The city has become the hub for aspirants who are desperate to crack the highly competitive engineering and medical entrance examinations and the coaching institutes have cashed in on this demand. Hailing from small towns, students are under tremendous family and social pressure to be one among the few who finally make it through.

Of the 1 million students who appear for the JEE exam only 10,000 qualify for the 23 IITs. Of the 2 million who sit for the NEET exam, only 140,000 bag a seat at a medical college.

The coaching centers have punishing and grueling schedules with students studying for 18 hours a day, seven days a week, with no time for any leisure. Fortnightly exams with marks being the sole defining identity of a student, add to the teenagers’ stress and anxiety. Since families often resort to taking loans to pay the steep coaching fees, the child has no option but to perform. Caught in between familial demand and inability to cope with the academic pressure, several students spiral into depression and in some instances kill themselves.

In January this year, 18-year-old JEE aspirant Niharika left a suicide note for her parents stating, “I can’t do JEE. I’m a loser.” The teen added she was killing herself since it was the “last option.”

Avijit Pathak, professor of Sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University writes of the “mythical notion of success,” which robs young adolescent students of their joy and laughter and makes them “recklessly one dimensional” for cracking the engineering/medical entrance tests. He describes the Kota suicides as symptomatic of all that is “ugly” in the educational system.

Rattled by the spike in suicide cases last year, the authorities directed hostels and coaching institutes to install “suicide proofing” fans in rooms since several of the suicides were carried out by hanging from ceiling fans. Routine tests conducted by institutes were also suspended for two months. However, these are at best stop-gap measures.

In January this year, the Union Ministry of Education issued strict guidelines to be enforced by all states to regulate the functioning of private coaching centers. Institutes have been barred from enrolling students below the age of 16. Moreover, institutes cannot issue misleading advertisements about guaranteeing ranks and good marks.

The move was prompted by the realization that these coaching centers have become ‘money-minting centers’ with little regard for student wellbeing. Students are cramped into classrooms with a single teacher sometimes teaching 300 students. They are compartmentalized and divided into sections according to their ranks and not alphabetically.

The commercialization of the coaching institutes can be attributed to the meteoric growth of the “coaching industry” in Kota, which is estimated to be worth around $500 million.

The intense competition to lure students has prompted institutes not only to aggressively spend on marketing and publicity, but also to poach students from secondary schools. As reported in The Telegraph, coaching institutes persuade parents to send their children for coaching while conveniently enrolling them as “dummy students” in select schools with which these institutes are tied up. Students are required to clear secondary schooling while no weightage is given to the school performance at the time of medical and engineering admissions. 16-17-year-olds, who would otherwise have been in the environs of a school, struggle with loneliness and cut-throat competition in the stifling surroundings of these coaching institutes. Far from home, students live in the cramped environs of Kota’s 4,000 hostels and 40,000 paying guest facilities.

The spurt in suicides last year led to a political blame game with the then-opposition Bharatiya Janata Party questioning the Congress government in the state. The latter had then issued a slew of measures, which among several things included prioritizing mental health counselling for students. Institutes are required to have trained counselors to help students and identify those in distress. Teachers are expected to undergo training in mental health issues. The local police and district administration have also been roped in. Police reported that helpline numbers to help students in distress had been able to avert a few cases of suicide.

Dr. Dinesh Sharma, head of the Department of Psychology at the Government Nursing College in Kota, who wrote his Ph.D. thesis on student suicides in Kota, said that in the course of counseling at least 400 students, he found that most suicides occurred on days when the fortnightly exam results were announced.

In his suggestions to the district administration, he proposed that fees should be charged quarterly and not for the entire course. This would reduce the pressure on students, who want to drop out of the course or are not able to cope with the stress.

Several educationists have emphasized the importance of counseling parents as they need to be made aware that their unrealistic expectations of their children are fueling the current spate of suicides. Even when children voice their anxieties to their parents, they are reprimanded and forced to continue studying at these “coaching factories.” Parents need to be counseled on holistic learning and allowing the child to pursue their interests even if it is in creative fields.

An analysis of students who died by suicide found that the majority of them belonged to poor and lower middle-class families from remote parts of north India. Most of them had ended their life within six months of arriving in Kota. The shame and guilt of not being able to fulfill their family’s dreams culminated in them taking their lives.

In comparison, the better-off southern states of India — Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra — offer more engineering and medical college facilities, and students here have more options than the handful of seats in prestigious IITs and government medical colleges.

It is ironic that despite the spike in suicides in Kota from 15 in 2022 to 26 in 2023, it did not figure as an election issue in the Assembly elections held in November last year. Rather politicians traded charges over failed promises to set up an airport at Kota, which would help to attract more students to its “coaching factories.”

The continuing spate of suicides this year, more than anything underscores the abysmal failure of India’s higher education system where political stakeholders perceive students as pawns for commercial benefit.