Some conspiracy theories are more realistic than others. One sticky, believable conspiracy theory says that Amelia Earhart didn’t actually die in some remote part of the Pacific, but that she was actually captured and killed by Japanese soldiers who suspected that she was an American spy. Purported new evidence that supports the theory has been aired at different times by The History Channel and The New York Times.

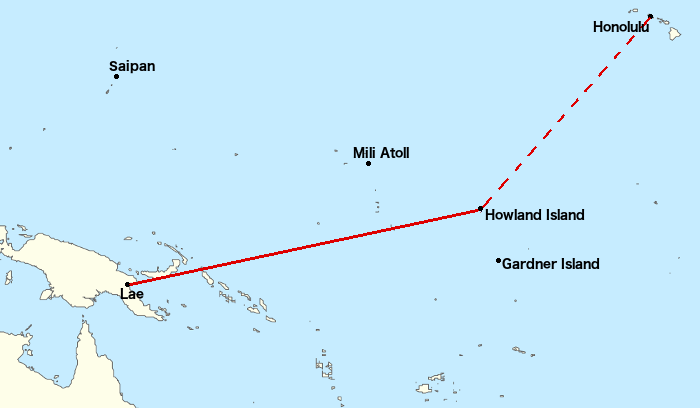

Earhart had become famous as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1937, she took on the challenge of flying all the way across the world. On July 2, 1937, Earhart was flying the longest and most challenging leg of her around the world voyage, from Lae, New Guinea to Howland Island, a tiny speck of land with an airstrip in the middle of the Pacific. She never arrived at her destination.

The U.S. Navy was called in to look for her, pulling in a force of 3,000 men, 10 ships, and 102 fighting planes who searched all over the Pacific. Earhart was assumed lost somewhere at sea, and eventually proclaimed to be dead on January 5, 1939.

The trip from Lae to Howland Island was risky, since this relatively small speck in a very large ocean was going to be hard to find. Adding to the danger, the 2,500 mile trip was so long that Earhart’s Lockheed Electra plane would have very little fuel left when she got to her destination. If she ended up getting off course, there would be little time to try to find land before she would run out of fuel.

Amelia Earhart’s final trip (solid red line), showing both her intended destination (Howland) and other candidate islands. Image by Snowfire, via Wikimedia Commons.

In theory, Earhart could have chosen a closer, safer destination. There were other islands that were closer. The reason Earhart didn’t choose one of the other islands was because she would not have been welcome. These islands were owned by the Japanese government, and relations between the United States and Japan were tense. Actually, these islands were a major cause of the Japan-U.S. tension.

The Imperial Japanese Navy didn’t take kindly to American visitors to these islands, and had banned Americans from visiting even back in the 1920s, long before the mounting tensions between the countries.

In fact, when the U.S. Navy searched for Earhart, they looked pretty much everywhere except for these islands, staying away to avoid a potential clash. And the fact that no one looked there gave credence to the conspiracy theories to come.

These Japanese islands, widely known at the time as “the Mandates,” included the Gilbert and Marshall chains. They had once been owned by Germany. Japan, fighting on the side of Britain in World War I, conquered these Pacific Islands and kept them after the war ended. Almost immediately, Japan had banned Americans and other foreigners from visiting.

Visionaries in the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps had known from the start that the Mandates would be key if there was ever to be a war between Japan and the United States. They were right about this, with islands such as Saipan and Tarawa ending up as the sites of some of the biggest island battles of World War II.

The commandant of the Marine Corps in the 1920s, John Lejeune, realizing that the United States knew very little about these islands, worked with a talented, well known, but mentally unstable officer named Pete Ellis to see if they could find out more. Ellis therefore went on a trip to these islands, posing as a merchant of coconut oil to give him a proper alibi to look around.

However, Ellis never was able to send his report on how suitable the beaches of these islands were for an invasion, because he ended up dead before he could go back and file his report. Ellis was a severe alcoholic, and it now seems likely he died of natural causes, but at the time it was suspected the Japanese had killed him as an assumed spy.

There were other reasons that U.S. Navy officers thought it plausible that Earhart had been killed by Japanese soldiers. A lot of it was the intense secrecy the Japanese held around the islands. The year before, the U.S. Navy had proposed an exchange of information to help build trust between the United States and Japan, where the U.S. would be allowed to visit the islands, and in exchange, the Japanese Navy would be allowed to inspect American islands off of Alaska. The Japanese turned down the offer, again making the Americans think something fishy was going on.

Yet another reason the U.S. Navy thought the Japanese could have killed Earhart was that they realized the Japanese Navy would have loved to get their hands on her plane. The Lockheed Electra was heavily modified to be a “flying laboratory of the latest innovations,” and the improvements were being adapted to long-range warplanes, such as Lockheed’s upcoming P38 Lighting. The FBI and Navy knew at the time that Japanese spies were attempting to get information from the Lockheed plant.

Amelia Earhart sitting in the cockpit of an Electra airplane. Photo by New York World-Telegram via Wikimedia Commons.

In theory, it is possible that Earhart (and her navigator) flew off course and arrived at a Japanese island, from which the Japanese Navy, realizing they had found the most famous woman in the world, decided the best thing to do was to kill her, while keeping the killing secret and not noting anything in any of their records. But given what we know about her voyage, it is extremely unlikely.

In addition to all of the above elements of the conspiracy theory, Earhart in her heavily loaded plane, flying at extreme range, would have needed to have enough fuel to even make it to one of the Japanese-held islands. From the course she was on from when her radio communications were last received, it would have been impossible. There just wasn’t enough gas in the plane.

In all likelihood, Earhart simply crashed somewhere in the vast ocean, never to be seen again.

This article is adapted from a chapter in the author’s newly published book, “Beverly Hills Spy: The Double-Agent Flying Ace Who Infiltrated Hollywood and Helped Japan Attack Pearl Harbor.”