Every exiled Uyghur carries a load: the “enormous pain, the hole in your heart, the burden on your shoulder and the nightmare in your sleep,” in the words of Yalkun Uluyol. Uluyol’s father is serving a 16-year prison sentence; an uncle has been condemned to life; and 30 or so other family members are serving long jail terms. Those not imprisoned have become coerced laborers or have simply disappeared.

The pain of separation never recedes; in fact it increases with the passage of time, he told The Diplomat. “Every exiled Uyghur feels like this to some extent or another.”

Seven years have passed since mass roundups, internments, and extrajudicial jail terms were foisted on the 15 million or so Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in his homeland, an area three times the size of France bordering the ex-Soviet Central Asian states, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Chen Quanguo, fresh from quelling dissent in Tibet was appointed as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s new governor in August 2016; his remit was to do the same in “restive” Xinjiang.

Under Chen, and on the orders of top leader Xi Jinping, more than 1 million Turkic peoples were swept into several hundred purpose-built, so-called vocational training camps scattered around the region, where “wayward” residents – mostly Uyghurs – were sent for “re-education” and to be “cured” of “ideological viruses” and the “mental illness” of Islam.

While the camps have mostly emptied since then, in their place a forced labor policy has been rolled out across Xinjiang, channeling camp “graduates” and scooping up 2-3 million “surplus rural laborers” deemed to be “idly” kicking their heels and thus “easily exploited by evildoers.”

Uluyol, 30, is an Istanbul-based foreign policy researcher and founder of the Uyghur Rights Monitor, a group set up in November 2023 to investigate Uyghur rights issues. The pain of losing his father has not eased despite the passage of time. “The world forgets,” said Uluyol, “but our relatives and friends are unforgettable.” In fact, he calls them the “unforgettable forgottens,” because while the rest of the world has largely moved on, those with missing or detained relatives cannot.

“People tend to believe that by time passing we can forget them and things become less painful. No! They do not,” he said emphatically.

Most diaspora Uyghurs have lost contact with loved ones in their homeland since 2017, when communication with overseas relatives could land you in jail. The majority were deleted from personal WeChat accounts, China’s main social media platform, leaving them with few options for contacting loved ones still within China. With no legal process or paper trail for the disappeared, Uyghurs abroad follow rabbit trails and an unreliable rumor mill as they search for the fate of family and friends left behind in Xinjiang.

Yalkun Uluyol’s father, Memet Yaqup, in an image taken in early 2018, in Guangzhou, shortly before his arrest. Photo courtesy of Yalkun Uluyol.

Uluyol spent two years trying to locate his father, Memet Yakup. The Guangzhou-based businessman had a successful trade exporting renowned honey melons from their hometown, Kumul, but Yakup disappeared sometime after their last conversation in 2018. His family, including his wife, who was caring for Uluyol and his sister Tomris while the siblings were studying in Istanbul, was suddenly cast adrift emotionally and financially both from him and the homeland. Only by searching for scraps of information through friends of friends did Uluyol eventually discover his father had been sentenced to 16 years in prison.

Survivors’ guilt is his constant companion. “My father, my uncles, everyone back home; none of them made it out, but I am here living a ‘normal’ life. I try very hard to overcome the guilt that I feel,” he said. Uluyol has turned that pain into motivation. “I try to remind myself constantly that it’s not my fault. It’s not my father’s fault. There’s an authoritarian regime that is making all the mistakes and we are the ones who are suffering.”

Nightmares still haunt him. “I keep dreaming about my father,” he added, “that I am going back and trying to rescue him from prison.”

“The other day I dreamed I was trying to visit my father through a Chinese lawyer and was also trying to escape from the security guards at Urumqi airport. I was also attempting to catch a last train to Istanbul. But then I woke up to find it had been a nightmare. Even in my dreams I cannot get to see my father,” he said.

Uluyol misses not only his father but the years they could be spending together: “I miss the memories we could be having.”

Both his grandparents have also passed away since they were separated. “It’s not just not being able to talk to them,” he said. “It’s also about the impossibility of talking to them anymore.”

Initially, Uluyol buried himself in research to expose the atrocities of forced labor and transnational repression in his homeland, but he has increasingly realized that he himself is a part of the Uyghur tragedy and wants to tell his own story.

Yalkun Uluyol giving evidence on Uyghur forced labor at the U.K.’s Foreign Affairs Committee in February 2024. Photo courtesy of Yalkun Uluyol.

He was due to address the EU Parliament in November 2023 with his findings on Uyghur forced labor in European supply chains, but with four days to go his 2-year-old daughter, who had been battling a congenital condition since birth, passed away. Everything in him wanted to stay at home to mourn but he decided to go.

“This was a turning point for me,” he said. “My little girl had struggled through nine surgeries and hung on for two years. She was a fighter and I knew I must be a fighter too. I realized this was my mission in life and the responsibility of my existence. I went not because I had to but because I wanted to.”

Nurmemet Mettursun, pictured outside his Istanbul medical clinic in 2023, mourns the loss of his father following his death in detention. Photo by Ruth Ingram.

Every exiled Uyghur has a story.

Nurmemet Mettursun, speaking to The Diplomat from Istanbul, where he works as a naturopathic physician, mourns his 67-year-old father, who he discovered had died five months into a five-year prison term. None of the family had been told the reason for his arrest or his sentence and his death had been put down to “old age.”

Mettursun’s 68-year-old mother, Tajinisa Yimin, was detained on “terrorism” charges in 2021 together with his 49-year-old sister, Muharrem Mettursun, but their cases have since gone cold.

Mettursun himself had been on a business trip to Dubai in 2016 when he heard the news that all visitors to Muslim countries were being arrested on return to China. He had no alternative but to flee to Turkey, unable to take his wife and two children with him. His first child, a son, was 5 years old when he left for Dubai. He has never met his second child, another little boy, born on September 11, 2016, soon after he arrived in Turkey. Seven years have passed and he has no idea where they might be. Depression and despair dog him every day.

Nurmemet Mettursun’s sister, Muherrem Mettursun, left, 49, was detained in 2021; their 68-year-old mother, Tajinisa Yimin, center, was detained on terrorism-related charges in 2021; and their father, Nuri Mettursun, right, was 67 when he was arrested in 2017. He died five months into a five-and-a-half-year sentence. Photo courtesy of Nurmemet Mettursun.

Istanbul-based Medine Nazimi, a Uyghur housewife with three children, has been catapulted from her “normal” life into the role of campaigner and activist, following her sister Mevluda’s disappearance. Mevluda had returned to their homeland after her studies in Turkey in order to care for their ailing mother.

Nazim told the Diplomat that she never set out to be a hero or an influencer but after publicizing her sister’s disappearance, more than 100 other frantic parents, husbands, wives, brothers, and sisters came forward, desperate for news of their loved ones.

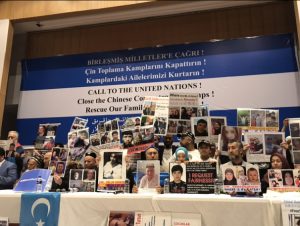

She founded the Chinese Concentration Camp Victims Group off the back of this and now spends her time juggling motherhood with lobbying governments, organizing awareness raising campaigns around Turkey, and calling the international community, China and the United Nations to account. “The Chinese embassy told me if I stopped my campaigning, they would see what they could do about my sister,” she said.

Medine Nazimi, president of the Istanbul-based Chinese Concentration Camp Victims Group. Photo by Ruth Ingram.

But instead of backing down, the group’s momentum has grown. They filed a case in January 2022 against 112 Chinese officials through Turkish courts, on behalf of 19 plaintiffs citing 116 missing relatives. They are pushing U.N. committees to press China on the fate of their missing loved ones. Nothing happens quickly, as U.N. mechanisms grind laboriously forward. And still they wait.

Zöhre Sultan, another Istanbul-based member of this group, told The Diplomat that 29 members of her extended family, mostly farmers, were caught up in the mass arrests and imprisonments. Some sent for “re-education” were released after between two-and-a-half to four years in a re-education camp. Others, ranging in age from 25 to 65, have been given jail terms of between 10 and 25 years. Two of them she said had died in prison.

“These people were ordinary, kind-hearted, hard-working farmers who had committed no crimes,” Sultan said. “We live with this injustice every day. Sometimes it is too painful to bear.”

Dilnaz Kerim (left) beside her mother, Hadiqe, at a Uyghur genocide protest in London. Kerim’s father, Kerim Zair, is between them in the second row. Photo by Ruth Ingram.

Dilnaz Kerim, the eldest daughter of a Uyghur family in exile in London, spends her free time campaigning against the atrocities in her homeland. The 21-year-old math major has lost 30 family members on her father’s side. “They cannot be found anywhere,” she said. Enquiries with the Chinese embassy in London have drawn a blank. “According to their records my uncle, my aunt and their families ‘do not exist,’” she said.

Kifaye Ehsan, 42, has been waiting anxiously since 2017 for news of her husband, Mehmutjan Memet, formerly a successful businessman trading in his hometown Korla’s fragrant pears. He had accompanied his mother-in-law back to Xinjiang in 2016 following a Hajj pilgrimage, but his passport was confiscated on arrival. His messages and calls stopped suddenly in September 2017 and she heard eventually through the grapevine that he had been arrested and sentenced on vague terrorism charges to 20 years in jail. His two younger brothers were condemned to life in prison.

Ehsan struggles to bring up their seven children on her own in Turkey. Since her meager savings ran out, she has been living on handouts from the Uyghur community and spare cash from her eldest child working in Istanbul. The hope that somehow they might all be reunited one day was dashed with the news in October last year that her 48-year-old husband was critically ill in the prison hospital with liver and heart disease. Guards at the Changji City prison confirmed to The Radio Free Asia Uyghur service his deteriorating health condition and that he was in need of “urgent medical attention.”

With the help of a human rights lawyer in Istanbul, Ehsan has been pressing the Chinese consulate in Istanbul for news of her husband and appealing on compassionate grounds for his early release to Turkey, but so far her requests have fallen on deaf ears and her correspondence returned unopened.

“We are beside ourselves with grief and worry,” she told The Diplomat, not having heard any news for the past few months. “My crying sets the children off so I try to put on a brave face, but all we can do is to wait and pray. We never stop thinking and worrying about him.”

Medine Nazimi, fifth from left and on her left Gülden Sonmez, the Uyghur Concentration Camp Survivor group’s Turkish lawyer, at a press conference in Istanbul March 13, 2024, announcinga U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention decision, confirming the arbitrary detention of their relatives in Xinjiang. Photo courtesy of Medine Nazimi.

In an attempt to keep track of the hundreds and thousands of disappeared, most of whom never hit the headlines, Russian-American researcher Gene Bunin and his team at Shahit.biz (shahit means “witness” in Uyghur) gave birth to the Xinjiang Victims Database, where the details of 79,082 arrested, detained, disappeared, and deceased individuals have been collated and updated daily since 2018.

In July 2023, a report released by London-based human rights group The Rights Practice detailed how Beijing has deliberately withheld news of Uyghurs interned between 2016-2017 in Xinjiang. Uyghur exiles seeking answers by asking Chinese authorities to trace family members inside Xinjiang are met with “silence, obfuscation, and threats,” creating an “intolerable situation” for those who wait, the report said.

Beijing’s unwillingness to provide Uyghur families with information about detained relatives has “brought misery to thousands,” said Nicola Macbean, executive director of The Rights Practice and author of the report. China’s actions, she said, contravene international law, amount to “enforced disappearances,” and “should be called out by other governments.”

“It has never been easy being a Uyghur,” said Uluyol, “but it’s harder now and getting harder.”

“Of course horrible things are happening in our homeland, but the diaspora too are in the midst of a crisis. They are experiencing extreme trauma, missing family members and are also experiencing financial and other repercussions.”

Yalkun Uluyol taking a selfie with his father Memet Yaqup, during the latter’s visit to Istanbul in May 2015. Photo courtesy of Yalkun Uluyol.

“Suddenly people who were successful professionals, businesspeople, and academics in Xinjiang have become refugees. This would always have been the last thing on their mind at home,” Uluyol said. “They had always dreamed of returning and contributing to society, but in an instant their dreams were cut short.”

Uyghur students studying in Turkey, severed from emotional and financial support, abandoned college. Some were forced to live on the streets, some turning to drugs and crime to get by. “They were in survival mode,” Uluyol said.

Some of those who have lost wives and husbands to camps and prison find new partners, make new families and move on as best as they can. But for many, their life has been put on hold.

For his part, Uluyol channels his energies into research. “It’s important for us and me to hold those people accountable and pay for their crimes; so that’s my motivation,” he explained. “I’m trying to move step by step to be a better person; to be a better husband, to be a better son, to be a better brother, and a better Uyghur for the community as a whole.”

“But the suffering and the pain never goes away. And it’s very hard to live with that.”

The last photo of Dilnaz Kerim’s father, Kerim Zair, and his family before all contact was lost in 2016. Zair’s mother is seated in the front center. The photo was taken at the family home in Shayar County, Aksu Prefecture, in southern Xinjiang. Photo courtesy of Dilnaz Kerim.