Next week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will host leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Melbourne for the second ASEAN-Australia Special Summit. The March 4-6 summit marks 50 years since Australia became the bloc’s first official Dialogue Partner, and will also be attended by Xanana Gusmão, the leader of aspiring ASEAN member Timor-Leste, and New Zealand’s Prime Minister Christopher Luxon.

The summit seeks to consolidate and build on the progress in ASEAN-Australia relations that has taken place under Albanese’s Labor government, which came to office in 2022 pledging to bolster the country’s relations with the region and ensure that its importance to Australia’s security and economic future was matched by a commensurate diplomatic commitment.

The government has since appointed a special envoy for the region and created an Office of Southeast Asia within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, modeled on the department’s existing Office of the Pacific. As promised, it unveiled a comprehensive economic strategy for the region – “Invested: Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040” – in a bid to deepen business and trade ties. Albanese also pointedly chose Indonesia as the destination of his first bilateral state visit.

Southeast Asia “is where Australia’s economic destiny lies, and this is where our shared prosperity can be built,” Albanese said in announcing the special summit at the ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum in Jakarta last year. “This is where, working together, the peace, stability and security of this region – and the Indo-Pacific – can be assured.”

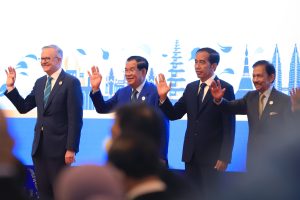

What can we expect from the summit? As Susannah Patton of the Lowy Institute noted in her preview of the summit, the first notable aspect is the number of new faces who will be attending, compared to the last special summit in 2018. In addition to Albanese, the leaders of Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam have all taken office over the past two years and are undertaking their first official visits to Australia. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. of the Philippines, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, and Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim are also taking the opportunity to hold separate bilateral meetings with their Australian counterparts while in the country.

Given that relations between Australia and its Southeast Asian neighbors have often promised more than they have delivered, the fact that such a summit is being convened is in some sense as important as the specifics of what will be discussed. That said, Australia has ensured that the official agenda is focused on a handful of key issues – climate and clean energy, maritime cooperation, and economic ties – that focus on areas of mutual interest.

Of these, economics is the perennial agenda item for the Albanese team, as suggested by the launch last year of the 2040 strategy document. The plan committed nearly A$100 million over four years to fund investment deal teams, internships for young professionals and support for Australian companies looking to enter the region.

Climate and clean energy are obviously key areas of cooperation. As Nicholas Basan argued in these pages last year, Australia’s technical know-how in areas like green energy and critical minerals make it an ideal partner for the massive private investments that are required to realize Southeast Asia’s enormous renewable energy potential. What impact the Albanese government’s efforts have over the short to medium term – as with relations in general, hope and rhetoric about the ASEAN-Australia economic relationship have tended to outpace the reality – remains to be seen.

Other issues will no doubt force themselves onto next week’s agenda. The most obvious is the conflict in Myanmar. As ASEAN’s most pressing regional challenge, this is likely to surface during the three-day summit, at least during the closed-door bilateral sessions. As with previous high-level ASEAN meetings, the military junta has not been invited to Melbourne. Like the United States and other Western countries, Australia has generally been content to support ASEAN’s own efforts to resolve the country’s crisis, even though these slowed to a crawl under the leadership of current ASEAN chair Laos. This makes it unlikely that the summit will produce anything beyond calls for adherence to ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus peace plan.

The issue of maritime cooperation will bring the summit into contact with one of the region’s most sensitive issues: the South China Sea. This has seen growing tensions over the past year, as the China Coast Guard has flexed its muscles in waters claimed by the Philippines, leading to a number of incidents in which Chinese and Philippine vessels have collided in contested waters. Marcos referenced these tensions at length during his address to the Australian Parliament yesterday, repeating his promise that he would “not allow any attempt by any foreign power to take even one square inch of our sovereign territory.” This suggests that the recent Chinese actions will be addressed during the summit, if only obliquely, given ASEAN member states’ varying degrees of relations with China and divergent stakes in the disputes.

This in turn points to perhaps the greatest area of potential divergence between Australia and ASEAN: how the two regions position themselves with regard to the tensions and intensifying strategic competition between the United States and China. Under Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Canberra committed itself to its U.S. alliance, mirroring the “China threat” rhetoric that has become commonplace in U.S. political discourse and enthusiastically joined the AUKUS pact in 2021.

While the initial Southeast Asian concerns about AUKUS appear to have waned with time, ideologically-tinged anti-China rhetoric has generally not gone down well in the region, where governments balk at any suggestion that they face a binary moral choice between a closed, China-led future and a “free and open” one under U.S. leadership. To take a recent example, in an interview with Financial Times last month, Anwar Ibrahim condemned the rising tide of “China-phobia” in the West.

“Why must I be tied to one interest? I don’t buy into this strong prejudice against China, this China-phobia,” the Malaysian leader said. He added that Malaysia seeks to maintain “good stable relations with the U.S. [while] looking at China as an important ally” – a similar desire to most, if not all, Southeast Asian states.

On this front, things are likely to be less rocky than they have been in the recent past. Foreign Minister Penny Wong, the descendant of Chinese-Malaysian immigrants, has criticized the Morrison government and its senior ministers for “relying on unhelpful binaries that reinforce existing prejudices of Australia in the region or reduce our complex environment to Cold War analogies.” Albanese has also succeeded somewhat in stabilizing Australia’s relationship with China, and arresting the downward spiral that took place under Morrison’s leadership – a deescalatory dynamic will no doubt have been welcomed in Southeast Asian capitals.

All told, the special summit represents a significant commitment of time, energy, and diplomatic resources to a region that is rightly described as central to Australia’s future security and prosperity. Looking beyond the close of the pageantry on March 6, the question that looms is the perennial one: how to bridge the gap between vision and reality.

On Australia’s part, this is something that probably requires a deeper reset of cultural and political expectations that are unlikely to happen over the span of a single administration. Even as past Australian leaders have extolled the importance of Southeast Asia, Alexander Lee wrote recently, they have tended to view Australia as standing apart from the region in which it is ensconced, “as an outpost of Western liberal democracy above all else.”

This is a worldview “that sees Australia continually looking beyond the region for security” – a perception that has endured, “even as economic links between Australia and ASEAN have grown to far exceed trade between Australia and its traditional security partners in Europe or North America.”

As a symbol of commitment, you couldn’t ask much more from next week’s special summit – but just as important is what comes after, and in the years to come.