While predicting China’s trajectory has always been fraught with danger, there are a few trend lines that provide some guidance.

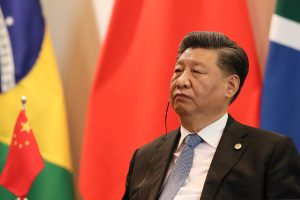

These trend lines stem from what the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Neil Thomas has astutely framed as Xi Jinping’s three “balancing acts”: balancing economic growth with security, balancing diplomatic “struggle” against the United States with avoiding economic “decoupling” from the West, and balancing “competition between different sub-factions in elite politics.”

Xi’s approach to each of these balancing acts suggest that while he may have achieved short-term gains in each, this success may simply prove to have kicked outstanding policy problems further down the road.

Xi’s ability to manage elite politics, for instance, appears on first blush to be relatively assured due to his success at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in October 2022 in stacking the party’s peak decision-making bodies (i.e. the 24-member Politburo and seven-member Politburo Standing Committee) with loyalists and establishing himself as both the “core” of the Party and its ideological fountainhead.

But this success could ironically set the stage for sub-factional rivalry among his loyalists, who are looking to build influence with an eye to what happens after Xi leaves the political stage.

A CCP elite primarily focused on intra-party positioning would likely be disincentivized to radically alter the policy directions that many external observers see as producing the stagnation of “reform” under Xi’s leadership so long as he remains politically active. This is symptomatic of perhaps the central paradox of CCP elite politics, as noted by Lowell Dittmer decades ago: that while cleavages within the elite are “the Achilles’ heel of the Chinese political system,” such cleavages offer “one of the few opportunities for political innovations taking a fundamental departure from an elite consensus which otherwise tends to rigidify.”

The final stages of Mao Zedong’s grip on the CCP appear apposite here. Back then, an uneasy equilibrium between the “Gang of Four” and the remaining “old guard” leaders such as Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping produced policy stasis.

Xi’s effort to balance between security and economic growth too is beset by contradictory trends.

On the one hand, the quest for security was a defining feature of Xi”s report to the 20th Party Congress – with explicit connections drawn between the “political security” of the CCP, domestic “stability,” and the achievement of “national rejuvenation.” On the other hand, “development” remains a formal priority. It is, however, a priority that is framed through the prisms of China-U.S. competition and the imperative of reorienting the Chinese economy to overcome major structural challenges stemming from an aging population, high youth unemployment, and rising income inequality.

Indeed, Xi’s major economic priorities such as revitalizing state-owned enterprises, reinvigorating state-led industrial policy, and promoting domestic innovation and technology development are geared toward “reducing dependence on imports and increasing self-sufficiency” and “can be equated with a ‘hedged integration’ to protect the Chinese economy from volatility from abroad, while still benefiting from selling in overseas markets.” Xi himself asserted in May 2023 that only by accelerating the construction of such a “new development pattern” could China not only ensure “our future development” but also attain “the strategic initiative in international competition.”

Xi therefore remains committed to a “techno-nationalist” fix for the geopolitical and economic challenges of strategic competition with the United States and the major structural constraints on the domestic economy.

This, however, comes with considerable risk, as reliance on a techno-nationalist solution will not only be an immense strain on government finances but also to be directed into the emerging technologies sector but also necessitate a decoupling from global sources of technology that could blunt prospects for domestic innovation. Xi’s commitment to this course of action, however, is consistent with what Guoguang Wu describes as his “worship” of the “magic power” of advanced technologies and faith in the CCP’s “capacity to mobilize resources” to “replace human creativity in furthering Chinese technological progress.”

Finally, China’s efforts to compete with the United States while avoiding and/or mitigating the risk of deterioration in relations with other major powers present contradictory dynamics. Beijing’s objective here, as Ryan Haas has suggested, is straightforward: to “center” China and “decentre” the United States in “international architecture” while opportunistically “probing for soft spots” in what it perceives as Washington’s “containment” strategy.

China’s recent efforts to that end are now embodied in three inter-linked initiatives, the Global Development Initiative (GDI) (announced September 2021), the Global Security Initiative (GSI) (announced April 2022), and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) (announced March 2023).

Each of these has been pitched as alternatives to what Beijing argues are the inequitable economic, security, and normative institutions and principles of the U.S.-led order. The GDI, for example, juxtaposes China’s “balanced, coordinated, and inclusive” growth model to that promoted by the West and makes the case for a focus on the “software” of development, including “knowledge transfer and capacity building.” The GSI, in turn, makes the case for what Xi terms “indivisible security” in contrast to the U.S. pursuit of its own (or its allies’) security through the use of security alliances and economic sanctions. Finally, the GCI contrasts China’s model for developing a “global network for inter-civilization dialogue” based on respect for civilizational difference and commitment to “refrain from imposing their own values and models on others” to U.S.-led efforts to impose “universal” values on others.

Taken together, the three initiatives seek to leverage misgivings among the broader international community about the current U.S.-led order. More importantly, as Michael Schuman, Jonathan Fulton, and Tuvia Gering note, they provide an illustration of the type of world order that Beijing would like to see: a world where state sovereignty and territorial integrity, noninterference in the internal affairs of states, and “state-focused and state-defined values system” are paramount.

This may appeal to some members of the Global South that remain at best ambivalent about Washington’s often tenuous and hypocritical application of the “rules” of the “rules-based order.” The emphasis on “civilizations” in the GCI is indicative too of China’s desire to elevate “states with linkages to ancient empires” such as itself and some of its current partners such as Russia and Iran as well as “Global South countries China is courting” while “deprivileging the voice of the United States as a relatively new and heterogeneous actor in ‘civilizational’ terms.”

Further development of these initiatives may assist Beijing in targeting “soft spots” in U.S.-led efforts to constrain it by leveraging Global South perceptions of the U.S.-led order as exclusionary and hypocritical. But they are unlikely to assist in rebuilding relations with those actors such as the EU, Japan, and Australia that remain closely aligned with Washington.

The risk here is that Beijing’s “initiative diplomacy“ will simply extend China-U.S. strategic competition “beyond bilateral relations to implicate the entire international community.” Whether this will be to Beijing’s advantage remains to be seen.

In pursuit of three balancing acts, then, Xi has arguably embarked on a series of actions that have privileged short-term gains while embedding long-term risks.