In the past two years, the United States and China have been riding a wave of hyper-diplomacy in a bid to turn down simmering tensions between the two sides. An already tense relationship has been repeatedly pushed to the edge by events such as then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei in August 2022 and the “spy balloon incident” of February 2023.

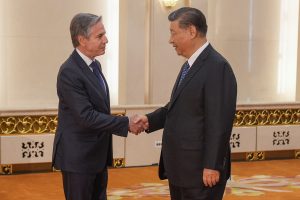

So when it was announced on April 22 that U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken will be visiting China for the second time in less than a year, it continued the trend of relative optimism. The expectation this time around was that Blinken’s meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Foreign Minister Wang Yi would at least reaffirm both sides’ commitment to resolving disputes and maintaining stability in ties. What we have instead observed is that disputes between the United States and China have become only more intrinsic and fundamental, and are keeping the two from reaching any significant breakthroughs in settling tensions.

What Was Said and What It Means

Blinken’s three-day long visit to Beijing and Shanghai comprised meetings with Xi, Wang Yi, and Chinese Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong. The context for his trip was set by various high-level conversations between the two sides since January 2024. These include the meeting between Wang Yi and White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in Thailand in January, the third and fourth meetings of the U.S.-China economic and financial working groups in February and April, the visit of U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Guangzhou and Beijing in early April, and the most recent meetings of Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink and National Security Council Senior Director for China and Taiwan Affairs Sarah Beran with counterparts in Beijing.

Subsequently, every “red line” issue challenging China-U.S. relations – from foreign policy-related differences on Taiwan, the Russia-Ukraine war, and conflict in the Middle East, to bilateral issues such as trade de-risking, sanctions and the fentanyl crisis in the United States fuelled by Chinese drug precursors – was tabled for discussion during Blinken’s visit. Acknowledging that the U.S. and China are in an era of competition, neither side seemed to budge on the abovementioned bones of contention. The deadlock was so pronounced that in remarks to Blinken, Xi Jinping argued, “no progress means regress,” signalling frustration due to the lack of any meaningful consensus between the two sides.

Similarly, in his meeting with Blinken, Wang Yi remarked that even though ties have “generally stabilized,” “negative factors are still growing and accumulating.” He hence doubled down on sentiments expressed by Xi, arguing that the U.S. according China the status of a “rival” rather than a “partner” is the “very first button” that must be put right. From what Xi and Wang have both communicated to Blinken, it can be inferred that China has outsourced the burden of peace onto the United States, and attributes any lack of dispute resolution to it.

Similarly, it was evident from the special teleconference conducted by the U.S. State Department before Blinken’s visit, that the goal for his visit was three-fold – “making progress on key issues,” “clearly and directly communicating concerns on bilateral, regional, and global issues,” and “responsibly managing competition… so that it does not result in miscalculation or conflict.” While little progress was made on the first goal, Blinken was successful in conveying to China that the United States has vital national security-related concerns that it will not budge on, and that it will not tolerate aggressive Chinese behavior potentially resulting in conflict.

What Are These Vital Concerns?

The United States and China have diametrically opposed stances on almost all subjects plaguing the relationship. On foreign policy-related issues, for example, Blinken was clear in communicating to Xi and Wang that China’s support for Russia’s defense industrial base is enabling its invasion of Ukraine, as well as “undermining European and transatlantic security.” This “support” refers to China’s exports not of weapons en masse, but of critical dual-use components such as microelectronics and machine tools, and rocket-propellant-grade nitrocellulose, to Russia.

Chinese officials argue that U.S. instructions to China on the matter amount to “interference” in “normal” trade relations. This is in line with the overall stand China has taken on the Russia-Ukraine war – for example, as per China’s 12-point “Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis,” released in February 2023, the core problem is not so much Russia’s aggression in Ukraine or the inability of the international legal architecture to mitigate the conflict, but the lack of a “balanced, effective and sustainable European security architecture” and the existence of NATO’s “bloc confrontation mentality.” The differences over relations with Russia now constitute a fundamental faultline between the United States and China, and have been a key motivating factor in the former sanctioning more than a dozen Chinese enterprises under the Entity List.

Similarly, Wang was firm in informing Blinken that the “Taiwan question” is the “first red line” that cannot be crossed by the United States. China has historically viewed U.S. arms sales to Taiwan as a key contributor to instability in cross-strait relations, while Washington has chosen not to back down from such endeavors. In fact, Blinken’s visit to China came just after the U.S. Congress passed, with bipartisan consensus, a bill to approve $8 billion in defense aid to Taiwan and the Indo-Pacific, indicating continued commitment to building deterrence in the region. The bill also contains provisions for war aid to Ukraine and Israel, and U.S. President Joe Biden, who vehemently supported the passing of the bill in Congress, also acted swiftly to sign it into law on April 24.

Among other things, trade and technology ties between the United States and China were also discussed during Blinken’s meetings, and as one would expect, the conversation was quite strained. It was ironic, for example, that while Blinken strongly condemned China’s “non-market, trade-distorting” economic policies and practices, he also continued to justify restrictions on the export of U.S. advanced technologies to China in the name of national security. U.S. policies on “open markets” and “fair competition” are being pinched by the fact that China dominates 100 percent of the supply chains in key sectors such as electric vehicles, EV batteries, and solar photovoltaic cells. In an equation such as this, trade and tech ties are being viewed especially by the U.S. as zero-sum.

Conclusion

Blinken’s China visit threw up every sign possible to indicate that relations between the two foremost global powers are fraying. While his meetings witnessed applause for the efforts of the China-U.S. working groups on climate change, artificial intelligence, and counter-narcotics, the reality remains that meaningful bilateral cooperation on any of these fronts is being hindered by mistrust. It is evident from U.S. suspicion of China’s dominance over critical green technology supply chains, from the competition between the two sides over state-of-the-art AI capabilities, and from the lack of resolution of the fentanyl issue, which the U.S. argues is fuelled by Chinese precursors entering through Mexico, and which China dismisses as a demand problem.

Given that competition between the United States and China will continue to remain a key feature of the contemporary geopolitical order, other countries can only hope the two sides can manage it responsibly. Avoiding miscalculations leading to conflict is in the interest of both sides, and so open lines of communication, above all other things, become important. In this light, even though Blinken’s visit highlighted many faultlines in China-U.S. ties, its success lies in its message of diplomatic outreach and in its attempt to enact guardrails in a relationship that is unlikely to bounce back anytime soon.