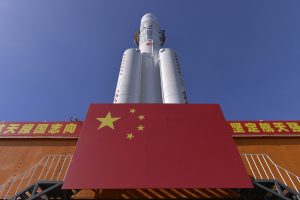

On April 17, NASA chief Bill Nelson cautioned that China’s “so-called civilian space program is a military program,” emphasizing that the United States is engaged in a space “race” with China. While NASA may have its reasons for securitizing this issue, one cannot overlook China’s rapid advancements in the space sector. China’s objective is to develop and acquire advanced dual-use technology for military purposes and deepen the reform of its national defense science and technology industries, which also serves a broader purpose of strengthening the country’s comprehensive national power.

China is actively pursuing space superiority while acquiring and developing counter-space capabilities and technologies. The U.S. Department of Defense’s 2023 report on China’s military highlighted three key takeaways regarding the People’s Liberation Army’s perspective and actions in space. First, the PLA considers “space superiority, the ability to control the space-enabled information sphere and to deny adversaries their own space-based information gathering and communication capabilities” as crucial aspects for conducting modern “informatized warfare.” Second, the PLA is actively investing in enhancing its space capabilities across various areas such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), satellite communication, navigation, meteorology, human spaceflight, and robotic space exploration. Third, the PLA is actively acquiring and developing counterspace capabilities and technologies, including kinetic kill missiles, ground-based lasers, orbiting space robots, and expanding space surveillance capabilities aimed at monitoring and potentially disrupting objects in space, thus enabling counter-space actions.

China’s military-civil fusion (MCF) strategy leverages civilian technologies for military purposes – in the space sector and beyond. This approach allows China to innovate and accelerate technological advancements rapidly, but also raises global suspicions of Chinese space activities.

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has brought to light the importance of space in military operations. A report by the Royal United Services Institute found that satellite technology, an instrument capable of augmenting Russia’s military performance, is already the focus of intense Russo-Chinese collaboration. Since 2014, Russia and China have engaged in discussions regarding collaboration between the Russian satellite navigation system GLONASS and its Chinese counterpart, Beidou. The following year, the two countries released a jointly developed multi-frequency radio frequency chip designed to support both constellations. These tools collect valuable imagery, weather, and terrain data; improve logistics management, track and predict troop movements, and enhance precision in identifying and eliminating ground targets.

China is bolstering its space-based radar and surveillance capabilities on its own as well. A case in point is the Yaogan-41, an optical imaging satellite operating in geostationary orbit. According to reports by state news agency Xinhua, this satellite will be used for “land survey, crop yield estimation, environmental management, meteorological warning and forecasting, and comprehensive disaster prevention and reduction.” However, some experts, like Clayton Swope, a former U.S. intelligence official, believe Yaogan-41 will allow China to continuously monitor the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Taiwan, and mainland China.

China currently operates the only synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) satellite in a geosynchronous orbit (GEO), the Ludi Tance-4. SAR technology can see through darkness and cloud cover, providing full-time, all-weather surveillance potential. China claims that Ludi Tance-4’s mission is purely civilian and aimed at land resource information, disaster prevention and response, and forestry applications. However, the use of GEO remote sensing satellites for civilian purposes is uncommon. Most remote-sensing satellites operate in low Earth orbit (LEO) because it is much easier, cheaper, and better – LEO produces sharper resolution because it is closer to the objects being observed on Earth. LEO satellites, however, lack persistent coverage as their orbit will continuously take target areas in and out of observational range. China’s persistent GEO surveillance capabilities could be used to locate and track the naval forces of India, the United States, and their allies in the Indo-Pacific region.

These are just some examples of many of China’s use of supposedly civilian space technology having massive military potential.

China has also developed and tested anti-satellite (ASAT) missile capabilities, which raised concerns and prompted responses from the United States. In 2007, China destroyed one of its non-functional weather satellites over 800 kilometers above Earth using an ASAT missile. This test generated over 3,000 pieces of trackable space debris, with more than 2,700 pieces still in orbit and expected to remain so for many years. The PLA also has an operational ground-based ASAT missile system designed to target satellites in LEO, and they continue to conduct training exercises involving ASAT missiles.

China intends to develop additional ASAT weapons capable of destroying satellites in geostationary orbit as well. In 2013, China launched an object into space on a ballistic trajectory with a peak orbital radius above 30,000 kilometers, near GEO altitudes. No new satellites were released from the object, and the launch profile was inconsistent with traditional space launch vehicles, ballistic missiles, or sounding rocket launches for scientific research. This suggests a basic capability could exist to use ASAT technology against satellites in geostationary orbit.

On the contrary, the Biden administration stated in 2022 that the United States is committed to refraining from conducting destructive ASAT missile tests in space and aims to establish this as a new global standard for responsible space conduct.

The United States is not alone in eyeing China’s space program with concern. India conducted its own ASAT missile test in 2019, 12 years after China’s. While the two nations were neck-to-neck in space capabilities during the Cold War, China has pulled considerably ahead with its space power. China operates 245 military satellites, while India operates only 26. India’s space budget for 2022 was $1.8 billion, significantly lower than China’s $12 billion.

India must ramp up its space sector to augment its military faculties. To achieve this, India needs to take decisive steps such as increasing its space budget, expediting the timeline for its dedicated military satellites, supporting its private space industry ecosystem, and partnering with other space-faring nations to boost space situational awareness in the Indo-Pacific region. These actions are crucial for India to close the gap with China and secure its position in the rapidly evolving and strategically crucial space domain.