The South Korean ferry MV Sewol capsized off the southwestern coast of the peninsula on the morning of April 16, 2014. Sewol’s departure from the port of Incheon the night before had been delayed by nearly two-and-a-half hours, due to a thick, persistent fog. Sewol commenced its journey shortly after the low visibility warning was lifted; it was the only commercial vessel to set sail from the port that evening.

Of the 443 passengers and 33 crew members on board, 304 lost their lives in the sinking. 250 of the victims were students from Danwon High School in Ansan, on their second-year field trip to Jeju Island.

As the nation bore witness to the minute-by-minute sinking of Sewol, it became obvious that this was an utterly preventable tragedy. As I summarized in a previous article:

It quickly became clear that this was an utterly preventable tragedy. The MV Sewol ferry had been illegally modified to carry more cargo and passengers than originally designed; when the ferry took an abruptly sharp turn on the morning of the 16th, the captain and the crew members were among the first to escape, and passengers were told to “stay put.” Those who followed the instructions through the loudspeakers never made it out of the ill-fated ferry, while the dispatched coast guard forces merely circled around during the critical minutes of the rescue operation.

As evidence of gross negligence, dereliction of duty, and breach of regulations piled up, citizens took to the streets out of grief and rage. The South Korean government and subsidiary bodies’ failure to respond as a “control tower” in a moment of acute crisis had already made the authorities a target of public censure; their ensuing attempts to suppress criticism, including arrests of peaceful protesters, tipped the scales.

The Sewol disaster ended up laying a crucial foundation for the first-ever impeachment of a democratically elected president in South Korea. When then-President Park Geun-hye’s flagrant scandal involving her confidante came to light in late 2016, leading to the largest mobilizations South Korea had seen since the Democratic Uprising in 1987, the Sewol families and allied citizens had already been holding weekly protests for months, demanding truth and accountability for the disaster from the administration.

In the mass protests calling for Park’s impeachment, allusions to, and commemoration of Sewol were rife: Protestors hoisted up large yellow ribbons – an emblem of remembrance and call for justice for Sewol – and Sewol families marched with a banner that featured the victims’ photographs.

In a short-answer poll taken by Hankyoreh newspaper in December 2014, the Sewol disaster was voted the second most important historical event in South Korea since the country’s independence, just 1.6 points short of the highest voted event, the Korean War. While the results could be attributed in part to the recency effect, it is difficult to dismiss the significance of a single disaster being voted as one of the most crucial events in the past seven decades, no less in a country that has seen a particularly tumultuous end to the 20th century.

What the Sewol Disaster Brought to Light

The Sewol disaster came to be seen as an illustrative “case in point” of the various ills that had gone unchecked throughout South Korea’s rapid ascension to a global powerhouse. It was Cheonghaejin’s breach of regulations that had made Sewol the most perilous ship in operation in the country, but the shipping company was not the only party to blame. Neoliberal policies that dated back to Lee Myung-bak’s conservative administration – during which several regulations concerning the maintenance and inspection of ships had been relaxed – had set the scene for continued malpractice.

Ten years on, two changes in administration, and three separate investigative bodies later, the bereaved families and citizens continue to search for answers and accountability. The scale and reach of the movement have inevitably waned over the years, and the mobilizations are a far cry from the early aftermath of the disaster. But the movement, led primarily by Sewol Families for Truth and a Safer Society – a collective of bereaved parents of Danwon High School students – and activists have been unwavering in their unified call for an exhaustive investigation into Sewol’s sinking and the botched rescue operation, accountability from culpable parties, and a thorough systemic change that would ensure that no such tragedy recurs.

The 4.16 Memory Cultural Festival in front of Seoul City Hall on Apr. 13, 2024, to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Sewol disaster. Photo via the 4.16 Network.

The Significance of the 10th Anniversary

Anniversaries hold particular significance for the families affected by the disaster, and the 10th anniversary is no exception. For many, it is a particularly painful reminder not only of the absence of their loved ones, but also of how little concrete change has been attained.

Lee Chang-hyun was one of the 250 victims from Danwon High School. Chang-hyun’s mother, Choi Soon-hwa, has been “demanding answers from the government, objecting, sparing no effort in her fight over the past ten years,” but the results that she sees today are “dejecting and despairing.”

Chang-hyun’s mother is right to point out that the search for justice and accountability has been time and again thwarted. As Park Sung-hyun from the 4.16 Foundation remarked: “There were lives lost, but no one held accountable.”

Park added, “if responsible parties are let off the hook, we won’t see anyone committed to saving lives in other instances of disasters.”

Indeed, only one low-ranking member from the Coast Guard has been held accountable for the mishandling of the rescue operations. Just two months ago, President Yoon Suk-yeol pardoned two army officers who had illegally collected intelligence about the bereaved families of Sewol victims to suppress “anti-government organizing.”

Yet, anniversaries also provide an opportunity. Efforts to mark this anniversary with meaning, and provide the movement momentum again, have been well underway for months. The 10th Anniversary Committee – steered by members of Sewol Families for Truth and a Safer Society, 4.16 Network, and the 4.16 Foundation – was made possible through the donation of more than 3,510 individuals and 445 organizations.

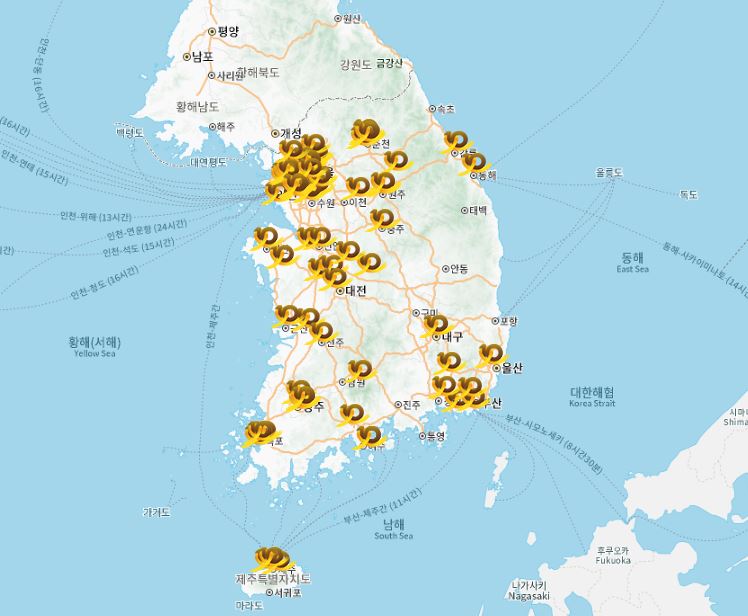

Ahead of the anniversary, the Committee organized a march across the country that spanned 21 days. Commencing in Jeju on February 25, the march came full circle in Seoul, in front of the Sewol memorial space. The Sewol families, walking through 21 major cities in South Korea, were joined in by citizens who have been amplifying their cause in their respective hometowns.

April has likewise been teeming with events in remembrance of Sewol, from screening and staging films and theater productions on Sewol, to street protests and rallies organized by grassroots collectives across the country. Someone, somewhere, is bound to be thinking about Sewol throughout this “month of remembrance”.

A map of Sewol-related events being held across South Korea throughout April. Map via the 10th Anniversary Committee.

Exceptionality of Disasters and the Banality of Risk

It has been mobilizations like these that have kept the Sewol movement alive throughout the past ten years. There is a far-reaching network of citizens across the country, each doing their small part. Together, that amounts to an impressive bottom-up solidarity.

As Choi, Chang-hyun’s mother met with citizens over the course of the march back in February and March, she saw clearly that “the shock and pain from the Sewol disaster ten years ago still live on in them.” Supporters saw the work toward uncovering the truth of the disaster not as a responsibility of the affected families alone, but as “homework to be brought to completion by our society.”

And this is one of the many ways in which the Sewol disaster’s legacy lives on in South Korea. While the Sewol movement continues to trudge along the path toward justice and change, it would be remiss to appraise the legacy of the event, and the affected communities’ campaign, based on prosecutions and court rulings alone.

On the night of October 29, 2022, South Korea witnessed yet another appalling social disaster. The Itaewon Crowd Crush claimed the lives of 159, most of them young people. For many, Itaewon’s parallels with Sewol were striking: foreseeable dangers gone neglected, a failure to deliver a timely response, attempts at a cover-up by authorities, and the ongoing search for justice and accountability largely left in the hands of affected families.

Itaewon drove home what Sewol had unveiled: the proximity of risk, an unaccountable political system that fails to assign responsibility, and a dire need for systemic change.

Over the past 10 years, Sewol families, in addition to their campaign for the truth of the disaster, have been extending their solidarity with other victims across the country, in manifold senses of the term: from families affected by comparable social disasters, including the Itaewon Crowd Crush to families fighting for accountability from business owners after losing their loved ones to industrial accidents. The empathetic reach of the Sewol families across these boundaries is yet another way Sewol lives on in South Korea.

The Center for Disaster Victims’ Rights opened in January 2024 as a subsidiary of the 4.16 Foundation, bringing together communities affected by eight major disasters over the past 30 years in South Korea. The first network of its kind in the country, the center provides an important foundation for sustained solidarity among communities affected by mass fatalities like the Sewol disaster, and for support in instances of tragedies alike in the future.

The precise tenors and textures of their grief, and their respective demands, vary. But what unites these communities is that they grieve for lives that are not yet fully grievable. These are deaths that cannot be fully mourned without an adequate explanation and accountability. As experts on mass fatalities and traumatic events highlight, their fight is part and parcel of the effort to bring order and closure – albeit partial and fragmentary – to lives overturned by an event that remains inexplicable.

Among the many things that Sewol brought to light is the sheer banality of risk behind exceptional catastrophes. It was the reckoning of a shared, omnipresent risk that brought hundreds of thousands to the streets in 2014. If we are to take the grief of the campaigning families, too, as in some part ours – or to use Chang-hyun’s mother’s words, “homework to be brought to completion” collectively – perhaps the subsequent anniversaries of Sewol may look a bit different than today.