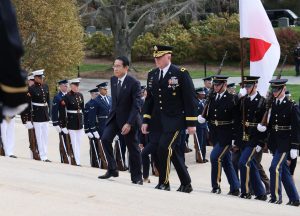

Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s state visit to the United States – highlighted by his meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden on April 10 – crystallizes the fundamental tenets of the Japanese post-war security architecture, while also affirming the new reorientations of the U.S. strategy for the Indo-Pacific.

This comes at a time of significant political realignment in Japan, as the different party ideologies coalescing in the delicate equilibrium over Japanese pacifism have shifted in recent years. The main opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party, has remained vocal in its vigilance toward expansions of Japanese defense ambitions. Last month, after the Kishida government announced a change to arms export regulations to allow the sale of next-generation fighter jets abroad, CDP legislators raised questions in parliament about the inevitability of Japanese combat planes being used for aggressive purposes. They also grilled Defense Minister Kihara Minoru as to whether Japan’s constitutional principle of peace has been properly discussed with current weapons manufacturing partners, including Britain and Italy, co-producers of Japan’s next fighter.

These debates highlight the thin line Japan is treading in regards to the principle of pacifism, and even how increasingly trivialized it seems to be becoming in practice. The change allowing the government to advance in its defense policy goals has been the gradual re-alignment of the traditionally pacifist Komeito party, the Liberal Democratic Party’s coalition partner. Komeito’s agreement made possible the loosening of the rigid Japanese weapons export regulations, the “Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology,” to permit fighter sales.

Shifting domestic politics has allowed for a steady accumulation of important evolutions not only in Japan’s defense capacity but also in its position in the liberal security architecture for the region. The U.S. Indo-Pacific Command seems keen to enable Tokyo to play a more central role, with a coming agreement on strengthening cooperation and more harmonious liaison between the command structures of the U.S. Army and Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF), a big sign of which is the expected establishment of the SDF’s new Joint Operations Headquarters by year’s end. During U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell’s visit to the U.S. embassy in Tokyo last month, he confirmed that the Joint Operations Headquarters heightened Japan’s autonomous capacity as well as its ability to take on greater defense responsibilities.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet decision passed last month again relaxing strict Japanese arms exports regulation paves the way for an unprecedented advance for Japan on the world weapons market. The current Japanese-British-Italian collaboration on a next generation fighter is allowing Japan to show its technological leadership on cutting-edge projects notably in propulsion (IHI) and software and sensors (Mitsubishi), after some failed military aviation projects of the 1980s, notably the General Dynamics and Mitsubishi F-2.

The still-debated enabling of counter-strike capabilities that would allow Japan to target distant enemy territory last fall is another sign of how Japan is steadily but successfully adapting its legal apparatus to play a larger role not only in its own defense but also in regional security. Faced with the reality of China and North Korea’s powerful cruise and ballistic missiles, Japan is putting missile deterrence at the center of its ramping-up of defense.

The creation of Japan’s Official Security Assistance (OSA) last April has allowed Japan to export “lethal equipment,” essentially military aid. The Defense Ministry’s rationale for the revision is a need to deter China, which follows the National Security Strategy’s overarching description of the current security paradigm as the most “severe and complex as it has ever been since the end of World War II.” Commentators criticize the “marketing” of the security framework, arguing that the existing Official Development Assistance (ODA) program was used as a benign-seeming template to tacitly establish a military program.

The steady accretion of policies this past year has made important advances bypassing Japan’s pacifist constitutional clause, equipping Japan with unprecedented capacities of ballistic retaliation and lethal weapons exports and collaboration. This is a legal and discursive evolution brushed over by those advancing new or alternate definitions of what Japanese pacifism can be.

When the OSA framework was being discussed last year, Gakushuin University’s constitutionalist Miho Aoi told Asahi Shimbun that “one can expect the world to find it strange that people die under weapons built by pacifist Japan.” But clearly, the Japanese administration is firmly and intently driven by its NSS of December 2022 and its commitment to “fundamentally reinforce Japan’s own capabilities.” This implies drastic changes for Japan as a military power both in its eyes and those of the world.

Domestic Obstacles for Japan’s Defense Ambitions

But despite these evolutions, challenges remain numerous.

When the Kishida administration announced its “revolutionary” military spending uplift in December 2022 upon the announcement of the new NSS, debates on the exact means to finance this went on for months in parliament, with the prime minister ceaselessly pushing back the exact financial contours. These debates seem to have lost importance in the ensuing year, mired in the current corruption scandal and the intense debates earlier this year surrounding the drastic expansion of social spending in the upcoming budget.

But recent reports highlighted Japan’s increasingly unsustainable sovereign debt, particularly in a cheap yen world and with the recent revolutionary overturn of the Bank of Japan’s decade-long negative interest rate policy. That debt is already burdened by Kishida’s vast endowments to child care and family policies, a bid to address Japan’s acute demographic downturn and labor shortage. That context would suggest the fiscal impossibility of Japan playing the role it dreams of playing in regional security.

The defense budget evolution outlined in the 2022 NSS planned an increase from 5.4 trillion yen (currently $36 billion) in 2022 to 8.9 trillion yen in 2027 ($59 billion) with an overall 5-year budgetary allotment of 43 trillion yen ($280 billion) – an ambitious feat, keeping in mind the cheapening of the yen that has occurred since. This followed the Kishida administration’s announcement at the time of the goal to progressively raise annual defense spending to 2 percent of GDP, which at the time effectively meant making Japan’s SDF the military force with the third largest budget in the world after the United States and China.

But the security documents are not legally binding. Observers should pay attention to Tokyo’s follow-through on its pledge, as the country’s new financial and borrowing situation could be set to drastically worsen the burden of debt repayment.

Putting budgetary restraints aside, one must then ask the fundamental question too willfully brushed aside by the government: to what extent can Japan’s industrial base support its security ambitions? Commentators marveled at the Nikkei Index historically surpassing its Bubble Era peak in February, with the weak yen and post-pandemic recovery partly rendering favorable conditions for a boom in market-value for Japanese exports. However, the BoJ’s Short-Term Economic Survey of Enterprises on April 1 voiced concern regarding the overall robustness of Japanese industry and notably the manufacturing sector, prompting a rapid decrease in the main stocks championing this year’s Nikkei surge.

The question of how Japan’s industrial champions will persevere – notably the semiconductor sector (Fujikura, Screen, Ebara, Electron, Fuji Electric, Advantest) and EV-related industry (Mitsubishi, Toyota, GS Yuasa) – is a main focal point of Japan’s capacity to reinvent itself as a leading technological force in the gold rush of the green transformation.

The Biden administration’s freeze of the Nippon Steel acquisition of U.S. Steel, which would make Nippon Steel the world’s third largest steel manufacturer, replacing China’s Ansteel Group, is also a major stress point for Japan’s industrial strategy. In the midst of this month’s buoyant geopolitical posturing, one can expect the deal to be the elephant in the room during Biden-Kishida talks.

Japan’s Defense Partnerships

On a diplomatic level, the never-ending questions as to actual U.S. commitment to Japan can be assuaged to a certain extent by what Washington is trying to signify this month. The United States is making Japan, in the words of CSIS’s Christopher Johnstone, a “true security partner in the region” as opposed to the bystander it has arguably been for decades.

The trilateral Japan-Philippines-U.S. summit in Washington on April 11 and the announced Japan-Philippines-U.S. naval exercises later this year are another example of the crystallizing regional coalition in recent years, with Tokyo taking diplomatic risks to welcome the Marcos administration’s new brazen communication style faced with the increase in South China Sea confrontations with China. As front-line countries to the expansion of China’s aggressive maritime and commercial tactics, Japan and the Philippines increasingly recognize each other as necessary collaborators on security issues.

Diplomatic convergence is underpinned by security cooperation. On April 7, the United States, Japan, the Philippines, and Australia conducted their first joint naval exercise, with Japan dispatching its destroyer, the JS Akebono, to the South China Sea. Dialogue on security cooperation at the trilateral summit will certainly highlight mounting Chinese aggression against Philippine vessels in the South China Sea.

Economic security will also be at the center of discussions, notably with the intention of strengthening cooperation on the supply and provision of nickel and rare resources. After Indonesia, the Philippines is the world’s second producer of nickel. With refinement and treatment capacities concentrated in China, the three countries intend to use the trilateral summit to advance resilience of supply chains but also to support the Philippines with small-scale nuclear reactors, 5G networks, and transport infrastructure.

Similarly, Indonesia under incoming President Prabowo Subianto might just prove to be the security partner Japan needs, with some analysts already including Indonesia in the top five most powerful global naval powers. Indonesia has been expanding its defense diplomacy; for instance Indonesia’s Super Garuda Shield military exercise last year included Japan as well as Australia, Singapore, France, and the United Kingdom.

Then-Defense Minister Prabowo’s visit to Japan early last month allowed the two countries to affirm their sharing of fundamental values and principles, their relation as “strategic” partners and desire to strengthen cooperation on defense and trade. The question of Indonesia’s traditional neutrality or non-alliance is ever-present as Prabowo’s first trip after his electoral victory on March 20 saw him travel to China, then Japan. But commentators have pointed at sources from Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry suggesting that while the Chinese visit was made upon Beijing’s invitation, the Japanese visit was instigated by the Indonesian side.

As a positive sign for Japan’s role and influence in Southeast Asia, the Singapore-based ISEAS’s most recent survey found Japan to be the most “trusted” country for government officials and academics in the region. For the sixth year in a row, Japan ranked in front of China, the U.S., the EU, and India. Most highly “trusted” in the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia, respondents cite Japan’s “respect and enforcement of international law” but also its “economic resources, political determination and global leadership.”

Japan has also bolstered ties with India, part of what Tamari Kazutoshi described as India’s major “direction shift” regarding China since 2020. India is becoming more assertive in its foreign policy and less circumspect with its gargantuan neighbor. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Japan last May and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s visit to Japan last month highlighted the strengthening of bilateral relations. This now shows in the deepening of India’s technological cooperation with Japan and the strengthening of economic security, notably using the Quad framework. Divestment from manufacturing dependence on China has increasingly become an undeniable concern, and New Delhi and Tokyo are obvious alternative partners.

The Camp David Japan-South Korea-U.S. summit last August and historical diplomatic reconciliation of Japan and South Korea over the past year are another testament to the encouraging trend that can be seen in the regional security architecture.

A constant risk for the liberal coalition in the Indo-Pacific will always be the electoral whims of domestic publics. Upcoming elections could return to power the Japan-resenting opposition in South Korea, the pro-China Filipino factions, the growth-minded Joko Widodo-like developmentalists in Indonesia, or of course a return to the foreign policy iconoclasm of Donald Trump in the United States. But the solidifying minilateral frameworks and joint military exercises form a solid bond, linking the region’s major powers against what are increasingly seen as common commercial and security threats.

With encouraging advances, the current industrial and policy evolutions in Japan are at a crucial but wavering intersection for Tokyo’s role as a guarantor of stability in the region at large. With export bans on China, the slowing Chinese economy, and the outsourcing of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry, Japan seems poised to contribute substantial technological and scientific expertise to global issues, even as analysts carefully follow the domestic tightrope walk of its rearmament and of course the strain on budgetary expansion that is Japan’s decades-long uniquely teetering sovereign debt.

In light of all this, the Japan-U.S. state visit this week will be crucial to read the geopolitical posturing and direction of the two largest liberal powers in the Indo-Pacific as security questions top the list of priorities during talks.