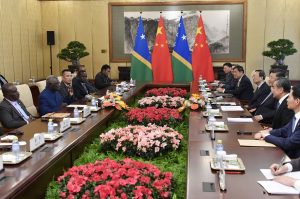

In the first general elections held since Solomon Islands switched recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019 – a decision that catapulted the country of less than a million people into the center of Asian geopolitics – no party gained a majority.

More than a week after the April 17 vote, a governing coalition has yet to emerge. Manasseh Sogavare, who has served as prime minister on four separate occasions since 2000 and shepherded through the Switch along with a security pact with China in 2022, was narrowly re-elected to his seat, but struggled to form a government.

On April 29, as two opposition parties struck a coalition deal, Sogavare withdrew from the prime minister race – saying his party would back Foreign Minister Jeremiah Manele. The parliament is expected to vote on May 8.

Amid the present political uncertainty, the only sure thing is that Solomon Islands is divided.

In a new book, “Divided Isles: Solomon Islands and the China Switch” journalist Edward Acton Cavanough takes readers to Solomon Islands to explain how the “Switch” played out on the ground. Cavanough draws on various voices, from the politicians behind the Switch to the dissidents who rose to prominence in opposing it. He also elevates the voices and experiences of ordinary people who have to live with the consequences of Honiara’s decisions.

In the following interview, Cavanough speaks to The Diplomat’s Catherine Putz about the Taiwan-China conundrum in Solomon Islands, the central figures in the domestic-cum-international drama surrounding the Switch, and the importance of paying attention to the political dynamics in small countries that nevertheless have global impact.

What precipitated Solomon Islands’ 2019 switch, after 36 years, from recognizing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China? Perhaps more simply asked: Why did the Switch happen when it did and not before?

The question of Solomon Islands’ allegiance to Taiwan has been a live one for decades in the country. The genesis of Taipei-Honiara ties dated back to a 1983 decision by former Prime Minister Solomon Mamaloni, and was done against the will of his then Cabinet. But over decades, the Taiwan relationship became entrenched in Solomon Islands culture and politics. Solomon Islanders saw in Taiwan a loyal friend; its political class saw an aid partner that, while providing much less than other countries, did so with fewer conditions. Taiwan had successfully integrated itself into Solomon Island communities — funding scholarships for bright young islanders, and engaging in grassroots aid and development. This made challenging the status quo difficult for most Solomons governments, even if they wanted to.

But over time, the value of the Taiwan relationship came under increasing scrutiny. The overall aid flow was modest, even if highly visible. And Taiwan didn’t have the heft financially to invest in the types of mega-infrastructure some in Solomons wanted.

The Switch really occurred in 2019 after being put on the agenda by a combination of local business elites and MPs who saw financial opportunities in normalizing ties with China. Many of these individuals had much to gain from a normalization of ties. After the 2019 election, some MPs even threatened [Prime Minister] Manasseh Sogavare with a no confidence motion if he didn’t pursue the Switch.

At the time, Manasseh Sogavare was in his fourth prime ministership. He was widely viewed as the driving force behind the Switch. How much of the decision to change recognition was driven by Sogavare’s individual political ambitions as opposed to some sort of consensus on the national interest?

Sogavare, in my view, has always been skeptical of the Taiwanese relationship. But he was not the original proponent of a Switch to China, and indeed didn’t campaign on it before the 2019 election. He saw the growing support for a China switch among his own MPs as a threat to his own power if he didn’t act. And he also saw in a China relationship an opportunity to both directly fund key projects he wanted to define his legacy, like the Pacific Games, as well as an opportunity for greater leverage over Western aid partners.

Sogavare is a skeptic of aid and development partners and their approach. He has clearly seen in a China relationship an opportunity to have more influence over existing aid and development approaches, by using the China relationship as leverage.

So Sogavare didn’t conceive the Switch. But he capitalized on it in a way that fundamentally strengthened his own political interests. The overall benefits to the country are harder to identify.

Daniel Suidani, who at the time of the Switch was the premier of Malaita, emerged as an extremely vocal point of opposition. How did the Switch play into his emergence on the global scene?

Suidani really came out of nowhere in 2019 to soon emerge as a major political player — the de factor opposition leader to Sogavare. He did this by leaning into the anti-China movement that had emerged on his island of Malaita Province. Soon after Suidani’s becoming premier, the Switch occurred, and a local protest group convinced Suidani to sign a communique which promised never to allow Chinese investment into the island. Suidani’s stance become well known globally. It irritated the Chinese, it was lionized by international commentators, and it saw this once unknown political figure emerge as a sort of David versus Goliath figure for all of those concerned about China’s rise.

In the aftermath, opposition to the Switch was concentrated most heavily on Malaita, where it dovetailed with existing tensions between the country’s most populous but poorest province and the center, rooted on Guadalcanal. But how much public support for the Switch was there on Guadalcanal or elsewhere in the country? What sense did you get about the divisions undergirding the split over Taiwan and China?

China hasn’t ever been popular in Solomons. This is certainly the case in Malaita, but it is true elsewhere, too. There hasn’t been a broad emergence of “pro-China” sentiment in Solomons since the Switch, even if the population are becoming used to the relationship.

And while Solomon Islander people were generally favorable towards Taiwan, we must remember that Solomons is a very young country. A new generation are now getting used to a Solomon Islands with no Taiwanese presence. And that nostalgic good-will, I think, between Solomon Islanders and the Taiwanese is beginning to fade.

Did you find any common threads that tie the tension over the China question with “the Tensions” that ultimately triggered the RAMSI intervention?

The Switch was a contentious decision made with littler serious public consultation. And the way in which it was done angered those on Malaita who, for a long time, have felt ignored in the national project of the Solomon Islands. This sentiment — the idea that Malaita, despite being the largest province — receives no real benefit from the aid and investment programs in Solomon Islands, and has the poorest living standards, were drivers of the Tensions and subsequent RAMSI intervention. So while the Switch didn’t relate directly to the Tensions, the way it occurred re-animated the sense that Malaitans were once again being ignored.

Almost five years have now passed. What have been the effects of the Switch on Solomon Islands? How has it affected the country’s economy and foreign relations? Is the issue still an irritant in domestic politics?

The China issue is still front and center in the national conversation but certainly not to the degree it was in 2019 and 2020.

The economic impact of the Switch has appeared negligible: While there’ve been some significant projects funded by the Chinese, most notably a major sports stadium, the benefits of this aren’t being seen in economic data in a significant way, nor on the ground in communities. The reality is that China has yet to invest in any projects that are really designed to solve long-term economic development issues. They’ve so far invested in projects that the Sogavare government wanted them to. For most people in Solomons, their lives remain stubbornly the same, despite all the fanfare.

What the Switch has done is put Solomons on the global stage. It has given Manasseh Sogavare extraordinary leverage over traditional partners, and seen Solomon Islands issues taken seriously by leaders as senior as U.S. President Joe Biden.

Pacific Island states get a lot of international attention when they are teetering over the decision to recognize China or Taiwan – the recent switch made by Nauru is another example – but very little attention is paid to them otherwise, let alone to the nuances and consequences of their domestic politics. Are there are lessons here for the international community: policymakers, analysts, and journalists?

I understand why smaller countries are often ignored in a broader conversation around international politics. But our tendency to do this often means we miss key drivers of international politics. The Solomons’ switch became one of the most important geopolitical events in the Pacific for decades. It fundamentally reshaped the region’s geopolitics. But it caught many observers flat-footed, because there hadn’t been nearly enough attention paid to the determinants of such an event within Solomon Islands.

Small countries matter, even if we don’t pay attention to them. Sometimes they’re in the driver’s seat in ways we underestimate.