After years of negotiations, the third iteration of the Compacts of Free Association (COFA) between the United States and the countries of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), are nearing completion. “Compact III” was signed into law in the United States on March 9, shortly after it was completed in Palau and FSM, and it is currently undergoing public consultation in RMI, with approval expected within weeks.

Understanding how the COFAs came to be, what is in them, and what they mean for a free and open Indo-Pacific requires a fundamental rethinking of “the Pacific Islands.”

How Did the COFAs Happen?

The COFAs are unlike any agreement the U.S. has with any other countries – because this region is unlike any other. A bit of (admittedly reductionist) history helps understand why.

The people of what are now Guam, the Commonwealth of Northern Marianas (CNMI), Palau, FSM, and RMI have a long history of excellence in seafaring. They crisscrossed the region for centuries until their first major colonization – by Spain. After the Spanish-American war (1898), the U.S. took Guam, and Germany (which already had the Marshall Islands) bought the rest from Spain.

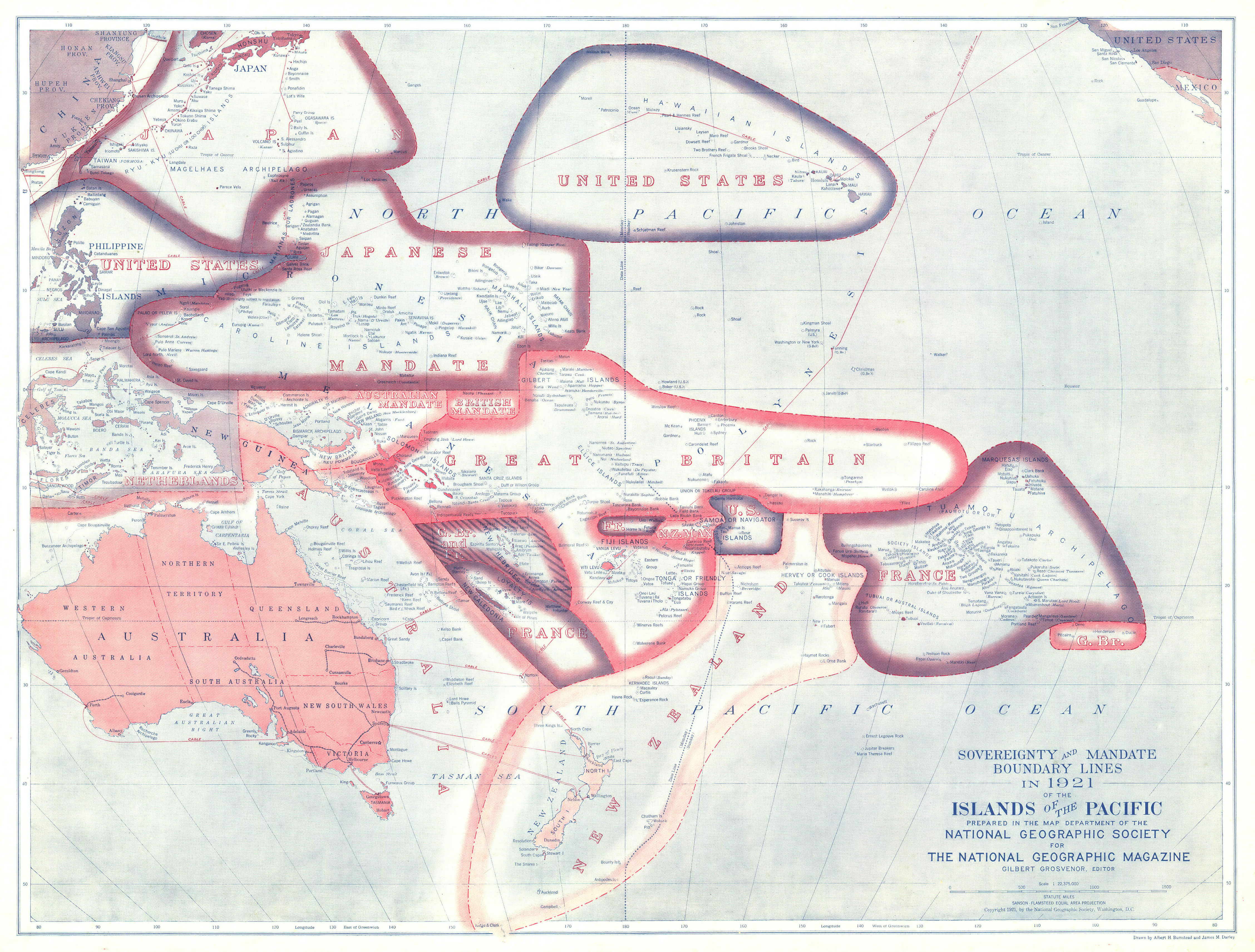

In 1914, Japan took Germany’s possessions during World War I, and was eventually awarded them as the South Seas Mandate by the League of Nations. Imperial Japan colonized the region and increasingly fortified it, allowing Tokyo to project power to areas near Hawaiian waters.

Map of sovereignty and mandate boundary lines in the Pacific. Source: National Geographic Society, 1921

After the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States launched an “island hopping” campaign to push Imperial Japanese forces back toward Japan. Some of the most difficult battles of World War II were in, or launched from, this area, including Kwajalein (RMI), Truk Lagoon (FSM), Peleliu (Palau) and Saipan (CNMI).

When the war ended, the region was given to the United States in trust by the United Nations. This “Strategic” Trust Territory consisted of what are now CNMI, Palau, FSM, and RMI. The post war years in the region were turbulent, including the Chinese Communist takeover of mainland China and the Korean War. During those years the Trust Territory was an active part of U.S. defense architecture, including 67 nuclear tests conducted in what is now RMI and covert military training in Saipan.

Eventually a Congress of Micronesia was set up, headquartered in Saipan, with delegates from across the Trust Territory who worked on the question of “what next?” Options were then put to popular votes across the region.

Map of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Source: U.S. government map, 1961

If you were from, say, Yap in FSM at the time of the vote, it is possible your grandparents would have remembered when the island was the hub for a German telegraph cable network laid to bypass the British network. Your parents might have learned Japanese at school and then hidden from American bombers targeting Japanese defenses. And you would have grown up during the U.S. Trust Territories period.

Throughout that period, fellow Micronesians passed through, some blown by the history, including the Chamorros who moved to Yap during the Japanese era and to Tinian under the Americans. And members of your family may have also gone to other parts of Micronesia, for marriage, education, health care, and so on.

Your family history was tied to empires that came and went. You knew your geography meant there was no hiding from geopolitics. You knew that by choosing to be close to the U.S., you would be part of the defense of America, and a target for America’s enemies.

Voting on Independence – and COFA

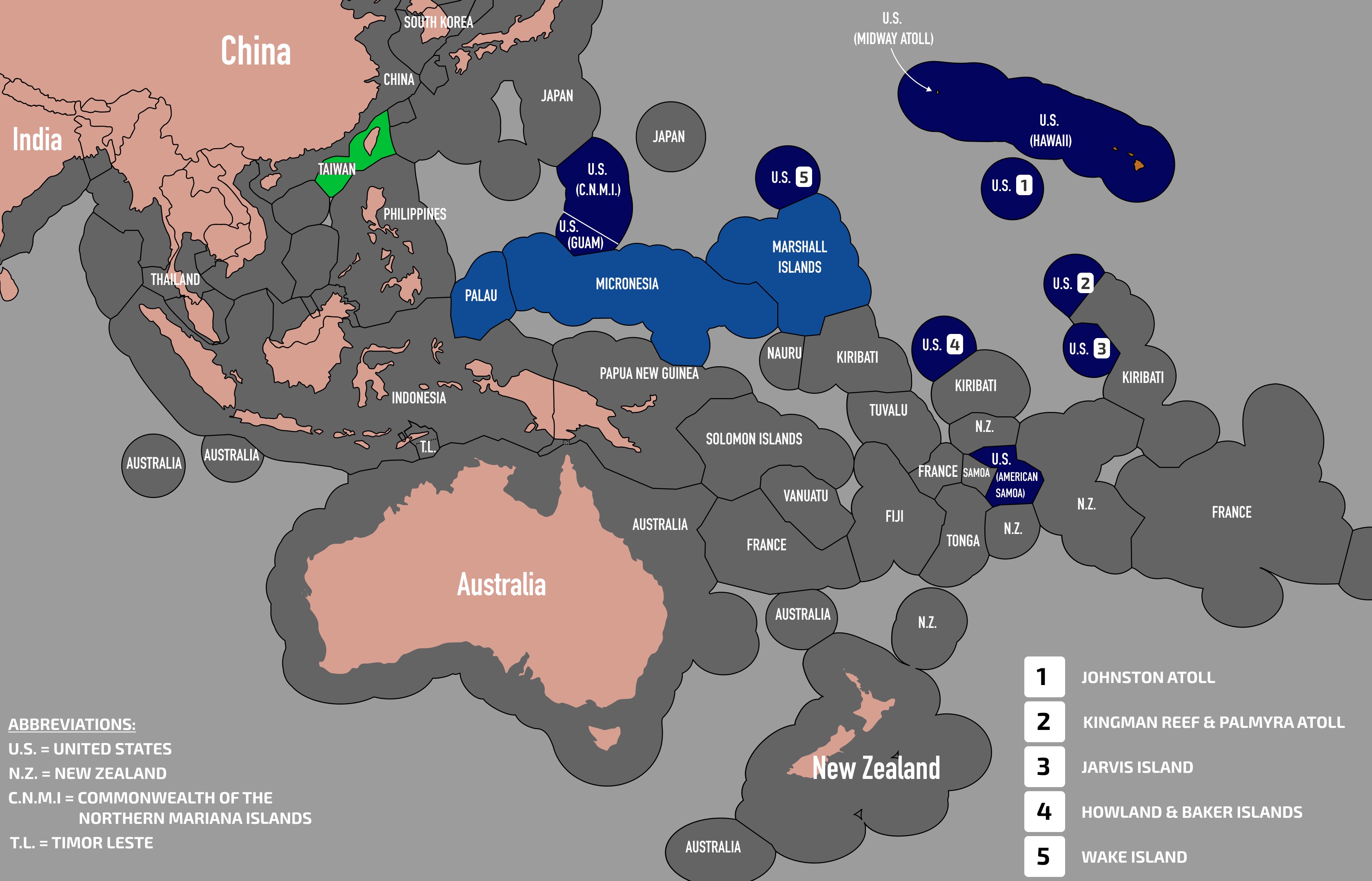

In the end, the people of CNMI voted to join the United States. The rest – covering a stretch of the Central Pacific around the size of the continental U.S. and running from just west of Hawaii to the Philippines and Guam – chose to form the independent countries of Palau, Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia. Those three countries also agreed to sign COFAs with the United States.

Through the COFAs, the three states have voluntarily granted the United States uniquely extensive defense and security access in their sovereign territories. In the words of the Compacts: “The Government of the United States has full authority and responsibility for security and defense matters in or relating to the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia [and Palau].” This includes a veto over other countries’ military access to the region.

This makes the freely associated states Washington’s most intimate allies by far; no other country gives the United States such access or trusts the U.S. so much with their security.

While often presented as transactional – the freely associated states get money; the U.S. gets an extended defense perimeter – the COFAs are much more complicated than that, especially when viewed from the point of view of the people of these states. As the former Trust Territory was going independent, then U.S. President Ronald Reagan said, in words often invoked by freely associated state leaders still today, “You will always be family to us.”

How Do the COFAs Create “Family”?

Every day the citizens of the freely associated states agree to put themselves between the U.S. and its enemies, they are proving their commitment to the “family.” But what’s in the hundreds of pages of the agreements themselves?

The COFAs are divided into sections. Some parts (for example defense and security agreements) continue until one side withdraws. Others (such as the provision of services) are periodically renegotiated, now on a 20-year cycle.

While there are many similarities in the COFAs between the U.S. and each of the three freely associated states, there are also differences. But, taken as a whole, they protect and foster a deep and unique bond between the three countries and the United States.

For example, unlike most citizens of other Pacific Island countries, citizens of the freely associated states:

- Can freely live and work in the U.S.;

- Can – and do, at very high rates – serve in the U.S. military;

- Have U.S. postal codes (mail to the freely associated states is charged at domestic U.S. rates, meaning, for example, they can order from Amazon as easily as Americans, no small thing given they are at the end of a long supply chain);

- Have school systems that are synchronized to U.S. systems, making moving back and forth and attending higher education in the U.S. easier;

- Have appliances that use U.S. voltage and plugs;

- Aren’t members of the Commonwealth;

- Use American spellings;

- Drive on the right;

- Have presidential electoral systems (not prime ministerial);

- Have access to U.S. weather services, the Federal Aviation Administration and other U.S. government services;

- Tend to favor U.S. sports like baseball and basketball rather than British ones like rugby.

To see just how deep this goes, here are some of the elements contained in the new Compact with Palau, divided into categories: those affecting the U.S. and all three freely associated states; those affecting Palau and Palauans in Palau; and those affecting Palauans in the U.S. This is far from a complete summary of what’s in the new agreement. There are similar provisions for the other two freely associated states, as well.

U.S. and the Freely Associated States

Some of the changes in Compact III are designed to solve some of the problems that dogged this round of negotiations. For example, to avoid the freely associated states falling through the bureaucratic cracks, the U.S. Department of State is now required to have a separate unit with four additional personnel focused on these states.

In addition, to ensure that the freely associated states don’t get boxed in by the “departmental equities” of State and Interior, the U.S. Interagency Group on Freely Associated States is now established by law, instead of merely by Executive Order, and its agenda is determined in consultation with the Defense Department instead of solely by the State and Interior Departments.

Furthermore, the interagency group is required to report to the U.S. president yearly on its achievements through the White House Intergovernmental Affairs Office – and the U.S. President, in turn, is now required to report on these annually to the U.S. Congress.

Palau/Palauans in Palau

Palau has a population of 18,000. Compact III includes $889 million over the 20 years to support, for example, health, education, public safety and justice, climate change and the environment, and auditing.

Compact III also grants authority to the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide U.S. military veterans’ health care in Palau, and to cover costs to travel for care if treatment is unavailable in the country. In addition, the U.S. National Health Service Corps will provide service in Palau and there is assistance to Palau for infants and preschoolers with special needs, mirroring the U.S. Individuals with Disabilities Act Part C program.

For infrastructure, Compact III provides for $5 million in FY24, increased annually by 2 percent for the 20 years of the agreement – reaching $7.28 million in FY43. There is also an additional $5 million in FY24 for maintaining infrastructure, increasing annually by 2 percent for 20 years, also reaching $7.28 million in FY43.

When it comes to financial matters, the rules for using U.S. financial assistance are now to be governed by Palau’s laws, which are simpler than the rules applying to U.S. grants. And the U.S.-Palau Advisory Group on Economic Reform has been renamed the Economic Advisory Group for Palau and will make recommendations to both governments regarding Palau’s economic needs (rather than just recommending reforms to Palau).

Palauans in the U.S.

There were a range of programs from which Palauans in the U.S. were excluded from eligibility in 1996. Compact III reinstated a number of them, including food stamps; supplemental security income assistance for low-income elderly and disabled Palauans; temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) for Palauan families in the U.S. with one parent who loses a job; and state social services block grant programs, which vary by U.S. state. Palauans in the U.S. are also eligible for in-state college tuition and Pell Grants.

The basic idea is that Palauans who live, work and pay tax in the U.S. are treated like – yes – family.

Lessons From COFA

For those thinking about “the Pacific Islands” the COFAs highlight several important points.

First, the South Seas Mandate/Trust Territories/freely associated states (and CNMI) region has a common history that is very different from that of the rest of the Pacific Islands. For example, Japanese ancestry is common, as are deep family ties to the U.S.

Second, the leadership of the freely associated states know they are on the strategic frontline and contend daily with major issues, including PRC spy ship incursions, complications with U.S. defense infrastructure plans, regular military exercises and, in the case of Palau and RMI, ties with Taiwan. This also means they are subject to constant PRC political warfare attacks.

Third, geography, history and travel links mean other north Pacific countries, including Japan and Taiwan, are much more important to the freely associated states than they are to other Pacific Islands. There are direct flights from Palau to Manila and Taipei, but getting to Canberra or Wellington can be expensive and lengthy. Also, local employment is very different. In Palau, many small shops are run by Bangladeshis, and Filipinos work across the region in a range of sectors.

This means Australia and New Zealand are of relatively low importance in the freely associated states. Additionally, concerns raised by other Pacific Islanders about access to work visas for agricultural labor in Australia and New Zealand have little relevance for citizens of the freely associated states who can freely work in the U.S. Nor, given their relationship with the U.S., have the freely associated states signed on to Pacific Island-focused trade agreements pushed by Australia and New Zealand, such as PACER Plus.

Additionally, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), calls itself the region’s “top political and economic organisation,” but both the politics and economics of the freely associated states are unlike any others in the region. Given the difference in priorities and realities, and the distances involved, it is not surprising the freely associated states thought the PIF was not an efficient use of their scarce time and resources and they had to be politically strong-armed in to rejoining.

Fourth, the idea that somehow the U.S. is a “lesser” Pacific Islands partner is deeply flawed. Apart from being a Pacific Islands country itself, including Hawaii, Guam, CNMI, and American Samoa, the relationships with the freely associated states are extraordinarily deep. Compare the depth of the U.S-Palau COFA with what Australia is offering Tuvalu in order to see the difference.

In light of this, reconsideration of the zone currently lumped together as “the Pacific Islands” is necessary.

While there are close ties across the Pacific Islands, the familial, cultural, and historic ties between CNMI and the freely associated states (and to a degree Guam) are especially deep. They are also tied together by the strategic imperative of geography. In the case of a “Taiwan contingency,” China would attempt to disable (at the least) U.S. military installations in Guam, CNMI, and the freely associated states. Their risk is exponentially higher than that of Tonga or Vanuatu.

Washington is starting to rediscover the value of the gift given to it by its family in the freely associated states. It would be appreciated in Palau, FSM, and RMI, and understood by the region (and indeed show the value of having a strong relationship with the U.S.), if those ties resulted in greater demonstrations of “family.” For example, no sitting U.S. president has visited any Pacific Islands. If such a visit happens, the first one should be to a freely associated state.

Also, the time is well past due for other nations to create policies that recognize the unique history, present and future of this important region.

For example, most countries base their diplomats to the freely associated states in other countries. India’s ambassador to Philippines is also accredited to Palau and FSM. Meanwhile India’s ambassador to Japan is accredited to RMI. It would make more sense for all three freely associated states to be handled by one office, perhaps Tokyo to facilitate Quad cooperation in the region.

Additionally, given their specific strategic reality, rather than forcing the freely associated states to focus primarily on the Pacific Islands Forum, more credence can be given to the Micronesian Presidents’ Summit consisting of the freely associated states as well as Nauru and Kiribati.

Modern map of the Pacific, showing exclusive economic zones. Source: Provided by author.

Bottom Line

The renegotiation and renewal of elements of the COFAs reintroduced the uniqueness and importance of the region to a new generation in Washington. While the process was tortuous, the fact it was one of the few major foreign policy laws passed during one of the most dysfunctional Congresses in recent memory makes it clear that, on this issue, there was deep bipartisan support.

But it’s not over. Implementation will need close attention, as will monitoring of malign influence in its varied forms. The importance to Beijing of weakening the ties between the U.S. and the freely associated states is in direct proportion to their crucial importance to a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Around 100,000 Americans died in the Pacific Theater in World War II and the people of the freely associated states lost family and saw ancestral islands obliterated. The COFAs were born out of that sacrifice. To ensure it wasn’t in vain, that unique bond must be acknowledged, nourished and honored.

This requires direct engagement and an understanding that while all “the Pacific Islands” are different, the freely associated states are special – and from an American perspective, they are family.