These are interesting times, but also troubling times in India.

India is rapidly approaching its 18th general election, and as the campaign for votes gains momentum, a serious apprehension is growing in a section of society and the academia that this might be the last election the country will see under the present constitutional framework; and that if the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, wins a third consecutive term, then the government will change the constitution.

Therefore, it is no wonder that the opposition-led by the Congress Party has launched a “Save Democracy and Save Constitution” campaign. The BJP has termed these apprehensions baseless and merely scaremongering.

Modi is a polarizing figure. Since he became the chief minister of Gujarat in 2001, he has never lost an election. In Gujarat, he trounced the Congress thrice, and after becoming India’s prime minister in 2014, he vanquished the opposition twice with the BJP winning majority numbers in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of parliament, on both occasions.

If he wins again in 2024, then, after Jawaharlal Nehru, he will be the only prime minister to have won three consecutive terms. Nehru is to be credited for laying the foundation of and building a modern-democratic-secular India. And if India today is a parliamentary democracy, then, the credit should go to none other than Nehru. He was truly a world statesman who had innate faith in India’s civilizational values and believed in India’s great tradition of unity in diversity, and also actively created a connection with the western world and encouraged the exchange of ideas with other civilizations.

But Modi is different. He is a product of the ideology of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which has never accepted the Nehruvian idea of India, has challenged its basic premise and termed the constitution a replica of the western thought process in which nothing is Indian.

In the RSS conception, India is a Hindu majority nation that other civilizations have historically suppressed for hundreds of years, and for Hindus to not face similar humiliation in the future, Hindus should be united. The RSS has been working on this civilizational project since it came into being and Modi forming the government at the center is the historical opportunity, in their opinion, to correct the mistakes of history. In the last ten years, the BJP, and the Modi regime has consciously changed the national discourse. Minorities, especially Muslims, have been demonized, and it has been inculcated in the minds of a large section of Hindus that India is a Hindu rashtra (Hindu nation) and minorities have no other option but to accept this fact and live as second-class citizens.

The opposition has been contesting this formulation but without much success. On the eve of national elections, its apprehensions have deepened as Modi has given enough hints that if he comes back as prime minister then “his government will take big decisions.” Though he has not spelt out what those decisions will be, his statements that the BJP will get 370 seats, and along with alliance partners, the number will cross 400, is indicative of his intentions. To initiate major changes in the constitution, the government needs a two-thirds majority, which means that the BJP has to win 363 seats out of 543 of the total seats in the Lok Sabha.

The Modi government has already taken a few steps to engineer fundamental changes in the constitution. A committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the former president of India, Ram Nath Kovind, to prepare a draft for “One Nation, One Election.” The committee has submitted its report to the government. Since Modi became the prime minister, the BJP has been arguing that elections to parliament and state assemblies should be held simultaneously, as that will not only save time, energy and money but also smooth governance. It is true that in India, every few months there is an assembly election in some part of the country or the other, which is a major distraction for governance, but it is also true that it keeps governments in check and makes them more accountable to the people. This system has been working fine for more than five decades. In this context, the opposition sees the “One Nation, One Election” exercise as an excuse to tinker with the constitution for the BJP’s long-term goal.

It is no accident of history that during the prime ministerial term of another BJP leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee (1998-2004), a committee was formed under the chairmanship of the former Chief Justice of India M. N. Venkatachaliah to review the functioning of the constitution. The committee submitted its report but nothing could be done because in 2004, the BJP lost the elections.

Since 2014, several leaders belonging to the Hindutva fold have suggested that the country needs to change its constitution.

“Our constitution was written based on the understanding of the Bhartiya ethos of our founding fathers, but many of the laws that we are still using are based on foreign sources and were made as per their thinking. Seven decades have passed since our independence…this is something we must address,” RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said in 2017, calling for a change in the constitution.

Recently, in the context of Modi asking voters to give the BJP 370 seats, a BJP member of parliament from Karnataka, Anant Hegde, said: “We need a two-thirds majority in Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and even in the state. All hurdles to rewrite the constitution will then go away and help us put Hinduism in the forefront.”

Arguing in favor of a new constitution, Bibek Debroy, a member of the prime minister’s economic advisory council, wrote that “a few amendments won’t do. We should go back to the drawing board and start from the first principles, asking what these words in the preamble mean now: socialist, secular, democratic, justice, liberty and equality. We the people have to give ourselves a new constitution.”

In December 2020, the CEO of Niti Aayog, Amitabh Kant, said that India has too much democracy, which hinders the pace of development. “So tough reforms are very difficult in the Indian context, we are too much of a democracy,” he said.

Although the Modi government and the BJP distanced themselves from such statements, the suspicion that it intends to change the constitution persists and is growing.

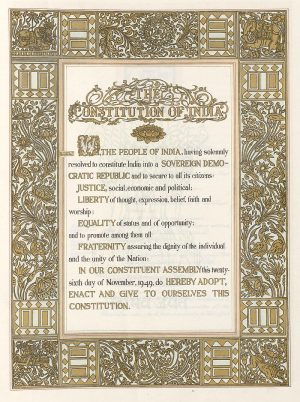

The Indian constitution is one of the finest legal documents in the world and has kept India a democracy for 74 years. Although the constitution has been amended more than 100 times, except during the Emergency in the mid-1970s, no serious exercise has been undertaken to undermine the basic ethos of the constitution.

Even the amendments made to the constitution are proof that it is not a rigid document but a living one that has the inner resilience to change with modern times and face any crisis. The question is if it has worked so fabulously till now, why the advocacy to change the constitution for a new one?

The opposition’s apprehensions are not without reason. The Modi government has not offered the nation a definite assurance that it will not change the constitution. Instead, it talks about how people need to decolonize their minds. India freed itself from British colonial rule in 1947, and has been a beacon of hope for all decolonized nations. In this context, the entire debate around the ‘new’ constitution and advocacy for ‘decolonization’ burdens us with the thought that the threat to India’s democracy is not from the outside but from within. That is why the 2024 elections are different from any election held earlier.