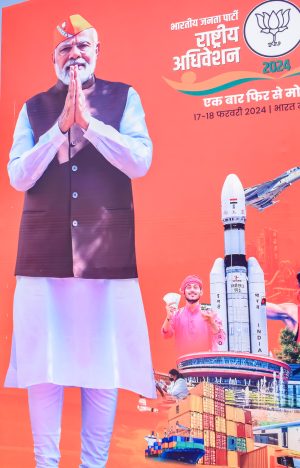

India has begun voting in its seven-phase general elections. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is widely expected to return to power in an electoral process that most international observers deem to be free and fair, despite some allegations to the contrary.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the BJP is extremely popular in India. He is, in fact, the world’s most popular elected leader, with 75 percent of Indians approving of his performance in March 2024. Opinion polls show the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) headed for a major victory and a third term in power: a recent survey conducted by ABP News-CVoter projected that the NDA would win 373 out of 543 contested seats in the Lok Sabha, with 46.6 percent of the vote. The opposition Congress-led Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) is projected to win 155 seats with 39.8 percent of the vote.

It is strange, then, that much of coverage of India’s election in the West is focused on concerns about the alleged ill-health of India’s democracy, despite the fact that a healthy contest is about to occur, in which the opposition is projected to get only a few percentage points less of the popular vote than the incumbent.

In truth, most Indians do not care about the occasional raid against a journalist or a magazine – a very narrow elite concern – but do care about a party’s overall performance, ability to deliver development, and vision. It seems that both at the popular level and the elite level, Indians have largely concluded that the BJP, and Modi in particular, is the best bet for leading India. Modi is seen as a strong leader who can make decisions, and who – as a nationalist – engages in rhetoric that gives the ordinary Indian pride in the trajectory of the nation.

To understand why, it is necessary to consider a number of factors relevant to the BJP’s popularity in India. The story of India’s politics isn’t simply a struggle between authoritarianism and democracy or communalism and secularism. Rather, voters also have goals and agency, and the BJP is popular because Modi embodies the hopes and dreams of the average Indian voter more closely than the opposition.

Development and Infrastructure

India is a very different place than it was ten years ago, especially for poorer, rural, and less-educated Indians. In sum, most Indians have now entered – and can interact with – the modern world because of improvements in physical infrastructure, internet access, and consistent electricity. This is a step in the direction of national integration: More Indians than ever are aware of and can be mobilized on issues of national, rather than merely local, import.

Infrastructure has improved dramatically under Modi. Under the present BJP government, more than half the population is connected to the internet, while the size of the national highway network has doubled. India has also built a network of semi-high-speed trains, the Vande Bharat Express.

Most importantly, the BJP focused on improving local infrastructure in ways that directly impacted individuals and families. Rather than letting private companies fill in the gap, the BJP government launched various programs to improve access to basic goods such as toilets and tap water. Under the Har Ghar Jal scheme, the number of rural households with tap water jumped from around 16 percent to 72 percent between 2019 and 2022. Similarly, during the tenure of the Modi government, over 110 million toilets were built, and the percentage of Indians practicing open defecation went from 50 percent to around 15 percent.

When weighing these improvements, it is not hard to see why Indians favor the BJP over the Congress Party, a party that has failed to provide the average Indian with the benefits of development for decades. There is no guarantee that a Congress-led government at the national level will perform any better than a BJP one.

The unemployment rate indeed continues to remain high. For youth in their early 20s, it is almost 45 percent. Much of this, however, is offset by the BJP’s direct transfer of cash to citizens, who are the beneficiaries of various schemes. While all Indian parties have engaged in such transfers for decades, the BJP has pioneered the digital transfer of cash, cutting out middlemen and corruption, and reaching more people than ever. The party has also excelled at taking welfare directly to marginalized groups such as women and adivasis (tribals).

Domestic Security

The Indian state suffered from major security crises throughout the 1980s and 1990s: the Khalistan movement in Punjab, the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, ethnic strife in India’s Northeast, and the Maoist insurgency throughout central India’s “Red Corridor.” Under other circumstances, India could well have Balkanized. The BJP is ideologically committed to welding India together into a strong nation-state; this is a core principle of Hindutva.

In practice, this has led to an emphasis on strengthening domestic security and enhancing national integration, a task that the Indian public perceives the Modi government to have done well. In central India, there has been a major drop in Maoist violence as states have combined greater policing with economic improvements, described by Home Minister Amit Shah as part of the BJP’s holistic approach to the issue. The Northeast, once a hotbed of separatism and ethnic violence, has become much more well-integrated into the Indian mainstream, partially because the BJP or its allies have sought and gained power in most states there.

Finally, the BJP is perceived to have greatly weakened militancy in Jammu and Kashmir by abolishing the erstwhile state’s autonomy by revoking Article 370 of the Indian constitution. Critics of the Modi government often cite the revoking of Article 370 as one of its more questionable decisions, but the move was extremely popular in India. Over half of voters surveyed in 2021 approved of the decision, primarily because it seems to have brought a sense of normalcy to Kashmir after many years of insurgency and economic stagnancy. Even the opposition Congress Party has dropped its support for restoring Article 370.

Vision

Perhaps the biggest difference between the BJP and the Congress Party lies in vision: What should India look like in the future? All major parties in India practice a mix of welfare distribution and caste calculations, even if the BJP has been better at it over the past decade.

However, Congress does not provide as compelling a vision of its idea of India as the BJP does. For this, the party may have Rahul Gandhi, its de facto – though not official – leader to blame. Gandhi’s notion of India seems to be different not only from that of the BJP but also from the majority of Indian citizens and even his own party. He once asserted that India was really just a union of states, and never really existed as a nation until the constitution bound it together in 1950.

Contrast this with the BJP’s view of India as a civilizational entity going back thousands of years, even if it was not always politically united. Which vision is going to resonate more with the average voter?

According to a Pew survey from 2021, 96 percent of Indians are proud to be Indian. On top of that, 72 percent of Indians believe their culture is superior to others, and 57 percent said that being Hindu was important to being “truly Indian.” Hindu voters also note that the BJP fulfilled its promise to build the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, a widely popular move. There is a huge divide between Gandhi’s sense of what India is and the beliefs of the average Indian voter.

On top of this, Congress and Gandhi do not enunciate a vision that is in sync with the expectations of a country about to emerge as one of the world’s preeminent nations. For example, in its 2024 election manifesto, Congress wrote that it “recognizes that national security is not enhanced by chest-thumping or exaggerated claims,” a mood that many other Indians, including other members of Congress, may not share.

Indians celebrate “chest-thumping”: According to a report from the U.S.-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in regard to the alleged assassination of Sikh separatist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Canada, “a commonly heard refrain in India is that while there is disputed evidence of the Indian government’s role, if it was involved, it would be a sign of the country’s emerging great power status. Such a reaction implies that India would have achieved the impunity to undertake the kinds of covert operations abroad that have previously been the hallmarks of richer, more established powers like Israel, Russia, and the United States.”

Moving to domestic issues, in its manifesto, the Congress Party proposed amending the Indian Constitution to breach the 50 percent cap for reservations. Gandhi recently gave a speech in Hyderabad where he promised a redistributionist state:

First, we will conduct a caste census to know the exact population and status of backward castes, SCs, STs, minorities and other castes. After that, the financial and institutional survey will begin. Subsequently, we will take up the historic assignment to distribute the wealth of India, jobs and other welfare schemes to these sections based on their population.

As seen in Venezuela and Argentina, a government committed to redistribution of wealth could engender mass poverty and inflation, the flight of capital, and a loss of global influence. This is hardly a formula for banishing caste to the past.

Do Indians want to be more like Venezuela or, say, Japan? The heart of the difference between the visions of Congress and the BJP comes down to a variation of this question. While the Congress Party focuses on redistribution, the BJP, meanwhile, envisions a state that is more like one of the East Asian “tigers,” with an emphasis on manufacturing, infrastructure, and nationalism.

The BJP Manifesto does not mention caste even once, does not promise any new future reservations, and mentions manufacturing 50 times – in quite some detail – as compared to six in Congress’ manifesto. The BJP government has sought to expand India’s footprint in industries critical to the world economy, including iPhones and semiconductors.

This is a difference in visions – even if manifestos don’t always match with reality. To many, it seems that the Congress Party is oddly averse to tangible developmental outcomes for India and is not as invested as the BJP in making India a world-class leader in the economic, scientific, and military realms because it chooses to focus more on redistribution and identity issues.

Most people, in any country, want their nation, within reason, to become a major military and economic power, and to feel pride in both their history and their future. The BJP, and Modi in particular, have managed to capture these emotions and aspirations much better than the Congress and Rahul Gandhi. This is why Indians want Modi again.