On May 3, China launched the Chang’e 6 lunar sample return mission. This mission aims to scoop up 2 kilograms of lunar rocks and soil from the lunar far side and bring it back to Earth. This 53-day lunar mission, which has already entered lunar orbit, is one of the most challenging missions undertaken by China, particularly because it targets the South Pole, Aitkin basin of the Moon.

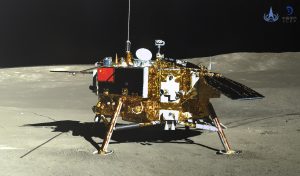

The challenges are manifold: Chang’e 6 carries an orbiter, a lander, an ascender, and a reentry module, specifically targeting the southern portion of the Apollo crater, which is about 490 kilometers in diameter. The site was chosen due to its rich variety of rocks, which will help collect a diverse set of samples. For the mission to succeed, the robotic arm must extend from the lander within 48 hours of landing, drill a borehole into the ground, and seal the collected samples in a container.

Wu Weiren, the chief designer of China’s lunar exploration program, highlighted the risks, stating, “Collecting and returning samples from the far side of the moon is an unprecedented feat… the mission is very difficult and risky.” But he also stressed the importance of the mission: “Now we know very little about the Moon’s far side. If the Chang’e-6 mission can achieve its goal, it will provide scientists with the first direct evidence to understand the environment and material composition of the far side of the Moon, which is of great significance…”

While China has already accomplished a near-side lunar sample return with the Chang’e 5, a far-side sample return has the added challenge of communications to Earth. Specifically for this purpose, China launched the Queqiao 2 (Magpie Bridge 2) relay satellite in March 2024 and placed it in a lunar elliptical orbit, to support communications from the Chang’e 6. The far side of the Moon faces away from Earth and that is why there is the requirement of this added communication infrastructure.

The Chang’e 4 that landed on the far side in 2019 utilized the Queqiao 1 relay satellite that China placed in Earth-Moon Largrange-2 Halo Orbit, about 455,000 km away from Earth. This system of relay satellites has been designed to support China’s ambitious plans of a cislunar communication infrastructure that will not only support future lunar missions – the Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8, aimed at surveying the lunar far side for the establishment of a lunar base by 2036 – but also go on to help develop cislunar space situational awareness. The entire design for China’s cislunar logistics and communication infrastructure, long in planning, has now entered the implementation phase.

There are major strategic and geopolitical implications of China’s Chang’e 6 mission. As I have written here earlier, China’s quest to develop long-term sustainable capacities for a permanent presence on the Moon would accomplish several vital things. It would enable China to develop lunar capacities to access the resources on the Moon like water-ice, helium 3, and rare Earth minerals like platinum and titanium. It would demonstrate China’s growth and maturity as a space power and cement China’s attractiveness as an international partner in difficult space missions. It would showcase the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as an innovative and science-driven party to both internal and external audiences.

In the last few years, since the 2019 Chang’e 4 and 2020 Chang’e 5 missions, China’s lunar missions have generated even deeper strategic and geopolitical implications.

First, demonstrating highly visible and difficult missions to the Moon, will offer enormous credibility and momentum to China’s lunar ambitions and timelines, especially if Chang’e 6 goes on to successfully collect the lunar samples, transfer them to the ascender, and then autonomously transfer it to the return capsule. The fact that China launched the Chang’e 6 on schedule adds reliability to its timelines for future planned missions: the Chang’e 7 (2026), Chang’e 8 (2028), a human mission to the Moon (2030), and the establishment of a permanent lunar base (2036).

China’s successes galvanize an entire space ecosystem within the country – one that includes not only state-funded space institutions but also commercial space ventures , supported by a vibrant investor platform. China has seen growing venture capital investments in key space technologies, like major Low Earth and Medium Earth satellite constellations that support high-speed satellite internet (launched by Huawei, G60, and Guowang), as well as reusable launch capabilities. Clear timelines have been stated for those missions as well.

The fusion between scientific endeavors and the CCP’s national strategy is clear. In April, based on all the data collected on the Moon so far from the Chang’e missions (1-5), the Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) released a Geologic Atlas of the Moon, available in Chinese and English. As per Ouyang Ziyuan, one of the foremost space scientists and the force behind China’s lunar program, “The geologic atlas of the moon is of great significance for studying the evolution of the moon, selecting the site for a future lunar research station and utilizing lunar resources” (emphasis added).

This lunar atlas has been developed since 2012 by Ouyang, Liu Jianzhong, and a team of scientists within CAS in an effort to provide scientific lunar data that is far more advanced than NASA’s lunar data gathered during the Apollo years. As stated by Liu, a senior researcher from the Institute of Geochemistry of the CAS, “The lunar geologic maps published during the Apollo era have not been changed for about half a century, and are still being used for lunar geological research. With the improvements of lunar geologic studies, those old maps can no longer meet the needs of future scientific research and lunar exploration.”

The scientists involved in the project stressed the post-Apollo era nature of the data, in some sense, bringing in the age of Chang’e. This kind of narrative – science-based and with clear evidence of a lunar resource utilization program – draws in international partners for China’s International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

The more China accomplishes in space, the more questions there are within the U.S. space community about legislation like the Wolfe Amendment of 2011, which bars NASA, the National Space Council, and the Office of Science and Technology in the White House from collaborating with Chinese state-funded space institutions.

This is what China has intended to a large extent by developing its indigenous space capabilities, based on a highly authoritarian, civil-military fused space program with a tenacious focus on meeting stated deadlines. Moreover, as per President Xi Jinping, Chinese space capacities, both civil and military, are part and parcel of turning China into a major space power, and becoming a global leader by 2049. We witnessed these aspects in the latest round of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) restructuring, with the establishment of the Aerospace Force as a separate arm of the PLA.

The Chang’e 6 has another major strategic and geopolitical implication. It helps develop China’s legitimate power to establish the rules of the road moving forward for the Moon. It challenges a Western-led international order and offers the CCP-led China as a legitimate alternative. Toward this end, China has established the protocols to develop an International Lunar Research Station Cooperation Organization (ILRSCO), as per Wu Weiren. Member nations of the ILRS will sign onto these “principles of operation” on the Moon.

These aspects were further elaborated upon by China’s position paper submitted to the United Nations Working Group on Legal Aspects of Space Resources Activities in March 2024. In the position paper, China highlighted its plans to:

…launch the Chang’e-6 lunar probe in the first half of 2024 to collect and bring back sample of lunar regolith from the backside of the Moon, and launch the Chang’e-7 lunar probe around 2026 to land at the South Pole of the Moon and hop over one or two shadowed areas to detect lunar resources, including water-ice. The Chang’e-8 lunar probe is planned to launch around 2028 for experimental verification of the utilization of lunar resources, and in cooperation with international partners China will establish the International Lunar Research Station over the next decade and verify in-situ utilization of lunar resources therein.

The position paper highlights the need for the regulation and the non-appropriation principles of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. It is, however, notable that the Chinese position is that space resource utilization is legal within the confines of the OST.

Contrary to its position on non-appropriation, the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by 2036 will throw up issues of how that China-Russia base will be regulated, and how the territory where the base is constructed will be shared with others who are not members of the ILRS. If China succeeds in constructing a base on the Moon, it means it will occupy a lucrative high ground, for both strategic and geopolitical purposes. China can then use its lunar base for showcasing both diplomatic and technological prowess.

Notably, the ambitions for China’s lunar base far exceed the U.S. Artemis base camp on the Moon. For instance, China and Russia have announced that they are building a nuclear reactor on the Moon for nuclear energy power generation. While the China-Russia plans are to generate 1.5 MW of power for a 10-year design life, the Artemis base camp plans on generating only 40 kW of nuclear power. For instance, according to Space Policy Directive 6, issued by the Trump administration in December 2020, the United States should “demonstrate a fission power system on the surface of the Moon that is scalable to a power range of 40 kWe to support sustained Lunar presence and exploration of Mars.”

China is utilizing the success of its lunar missions to draw in partners. Besides countries like Pakistan – whose first lunar cubesat, ICUBE-Q, designed by the Pakistan Institute of Space Technology, was also successfully released by the Chang’e 6 mission – Russia, Belarus, South Africa, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Thailand, Venezuela, and Egypt are members of the ILRS. The United Arab Emirates’ Sharjah University has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to collaborate with the ILRS. Kenya’s Kenya Advanced Institute of Science and Technology and Ethiopia’s Space Science and Geospatial Institute also signed MoUs to partner with ILRS.

On April 24, China celebrated its Spaceflight Day with announcements for new partners for its ILRS. These included Nicaragua, the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization, and the Arab Union for Astronomy and Space Sciences. Turkey, a NATO member, has applied for membership in the ILRS.

China’s Chang’e 6 mission will be a game changer for China’s space program, if it succeeds in collecting the lunar samples from the far side of the Moon and returning them to Earth. It proves the technological and political commitments of the CCP to turn China into a 21st-century space power. This lunar mission forms an integral part of a much grander Chinese ambition: to establish a permanent presence on the Moon and become a geopolitical leader that shares its space prowess with others, especially with nations in the developing world.

China’s space success obscures several of its intrinsic internal realities: the civil-military fusion aspects of its space program, and the absolute loyalty that all institutions within China, including its space institutions, have to give to the CCP. Nothing can be above China’s national interest, focused on its goal of national rejuvenation and emerging as a technological leader by 2049. China’s space success is part of that comprehensive national power building.