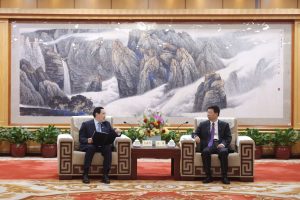

On April 10, former Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou met Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Observers reported that the two men shook hands for 16 seconds, in a particularly enthusiastic greeting.

Ma was likely visiting China in an attempt to ease cross-strait tensions in light of the upcoming May 20 inauguration of new President Lai Ching-te (also known as William Lai), as well as the handling of recent incidents around Kinmen Island. Although his China visit was not entirely without support in Taiwan, naturally there was no praise for Ma from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while the response from Ma’s own Kuomintang (KMT) was also rather muted.

Ma made it clear during his meeting with Xi that he opposes Taiwanese independence and is in favor of maintaining the 1992 Consensus. However, although both sides apparently mentioned that they would firmly uphold the “one China” policy, neither spoke of what each meant by “one China.” It is doubtful that China ever had any intention of doing so.

Ma was not representing the Taiwanese government, nor even the KMT. He was visiting China was in his capacity as a private citizen, and not as an envoy formally entrusted with any task by the government or the KMT. Nonetheless, Ma seems to have argued that if Taiwan Strait tensions were to escalate, Taiwanese society would become unstable, and so Chinese people on both sides of the strait should put their heads together to avoid conflict.

Ma said that the Chinese people have undergone a “century of humiliation” but that they have enjoyed 30 years of revitalization thanks to the efforts of Chinese people on both sides of the strait. The reference to “30 years” here is probably because Ma wanted to imply that it is thanks to the 1992 Consensus that Chinese have enjoyed a “revitalizing.” Ma’s view is also that “Chinese” includes the people of Taiwan. Ma holds that the 1992 Consensus has been the foundation of cross-strait relations, and that it is only through this consensus that Taiwan will prosper – a position he held when he was Taiwan’s president.

Even if Ma was not officially representing the KMT, he remains associated with the KMT, and so his actions will have at least some implications for the party. The discourse over the 1992 Consensus in fact places considerable pressure on the KMT. Put simply, the more talk there is about adhering to the 1992 Consensus, the lower the KMT’s approval rating falls in Taiwan.

Among the people of Taiwan, more than 60 percent want to maintain the status quo, 25 percent want independence, and fewer than 10 percent want unification. In terms of identity, fewer than 3 percent of Taiwanese clearly identify themselves as Chinese. Thirty percent of respondents meanwhile say they are both Chinese and Taiwanese, while about 60 percent say they are Taiwanese. Neither “one China” nor “we Chinese” are likely to resonate with the majority of people in Taiwan today.

For this reason, the KMT cannot fully get behind Ma’s initiative. In particular, from the KMT’s perspective, having won the legislative election and gearing up to serve as the opposition to the new government of Lai Ching-te, it wants to capture as many independents as possible, as they make up more than 40 percent of Taiwanese voters. With that in mind, public expressions of support for Ma are unhelpful.

For his part, Xi has gained some good promotional material for his domestic audience. He can point to the existence of politicians like Ma in Taiwan and use this to assert the “correctness” of the Chinese Communist Party’s Taiwan policy. If China makes skillful use use of Ma’s visit and combines that with an emphasis on “peace” rather than armed aggression, then Ma’s trip may ultimately prove to have been significant.

However, if the visit only reinforces Chinese misperceptions about Taiwan, then even with a short-lived boost to the “peace” narrative, the long-term outcome may be the growing entrenchment of an understanding of Taiwan that is at odds with reality.