Tajikistan is finally taking issue with the treatment of Tajik nationals in Russia, a month after a distinct spike in xenophobic attacks and commentary directed toward Tajiks in the wake of the March 22 Crocus City Hall attack.

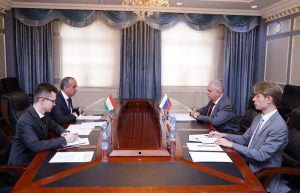

On April 26, Russian Ambassador to Tajikistan Semyon Grigoriev was invited to the Foreign Ministry for a meeting. During the meeting, according to a pithy Foreign Ministry readout, the Tajik side raised concerns about “problems” faced by Tajik nationals crossing the Russian border, specifically what it termed “widespread” and “unfounded” refusals of entry. The readout did not identify whom Grigoriev met with, but a photograph released with the statement shows Deputy Foreign Minister Sodik Imomi, as identified by Asia-Plus.

A day later, the ministry posted a single-sentence advisory recommending that citizens “temporarily refrain from traveling to the territory of Russia by all means of transport.”

Tajikistan’s restrained warning comes a full month after neighboring Kyrgyzstan issued a far more detailed warning to its citizens, despite reporting that Tajiks in particular have been the subject of increased xenophobic abuse, deportation, and denials at points of entry.

On March 24, the four main suspects in the Crocus City Hall attack – all Tajik nationals – were paraded into a Moscow court. Each bore clear signs of torture; videos of their abuse at the hands of the FSB circulated widely on social media.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t until April 12 – three weeks later – that Tajik Foreign Minister Sirojiddin Mukhriddin criticized the torture and abuse directed toward Tajiks. At a meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) Council of Foreign Ministers in Minsk, he called the torture “unacceptable” and condemned the surge in xenophobia as the result of an “ill-considered information campaign.”

As political anthropologist Malika Bahovadinova explained in a recent interview with The Diplomat, “Racialized violence was always part and parcel of mobility to Russia, with Tajikistani citizens often bearing the brunt of such violence for no reason other than being representatives of the least protected group.”

When asked to what extent the Tajik government cares about the safety and conditions of its citizens working abroad, Bahovadinova said “not much.” She went on to characterize the foreign minister’s condemnation as “too little and too late” and explained in detail the dynamics between Russia and Tajikistan that perpetuate the present system.

Bahovadinova’s interview was conduced in April, before the latest developments, but nevertheless was prescient in framing how we can understand Dushanbe’s shift.

“The lack of protection that we have seen over the past decades of racialized abuse speaks volume about the lack of any ‘social contract’ between the Tajikistani state and migrant workers,” Bahovadinova said. “If there is a contract, it is only one that feeds on migrant labor and their remittances, but which provides no responsibility or protection.”

What has motivated Dushanbe to finally warn its citizens against attempting to reach Russia? The apparent threat of a breakdown in that contract.

On April 28, the day after issuing its advisory against traveling to Russia, the Tajik Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed media reports that, as of April 27, 954 Tajik citizens were being held at Vnukovo International Airport in Moscow. The statement complained of the poor sanitary conditions in the holding area and noted that Tajik diplomats, in cooperation with diaspora groups, were delivering food to those detained – citing a lack of sufficient hot food being provided by the Russian authorities. The foreign ministry’s statement noted that 322 people were eventually allowed to enter Russia, 306 people were put on lists to be denied entry and expelled, and 27 people had been deported. The ministry cited “complicated” situations at Moscow’s other airports.

As much as Russia needs migrant labor, Tajikistan needs to export such labor – or rather, Dushanbe has continually failed to address the local economic dynamics that make it unable to support a growing population with jobs or sufficient opportunities. This has been a mutually beneficial (at the elite political level, at least) arrangement for three decades. But with the Crocus City Hall attack putting pressure on the Russian authorities, Moscow’s calculations have shifted and Tajiks make a ready scapegoat for the state’s security failures. As such, Dushanbe has been forced to act to try and preserve the status quo because the alternative is unfathomable.