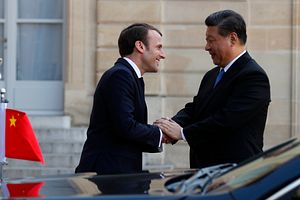

With the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations looming, Chinese President Xi Jinping will be welcomed in Paris – and in the Pyrenees, a childhood retreat dear to President Emmanuel Macron’s heart, to add an intimate touch aimed at strengthening ties. Beyond the symbols, however, what can this protocol visit bring?

Xi’s trip comes just weeks after Olaf Scholz, the chancellor of Germany, paid a visit to China. Germany remains, despite its difficulties, the heavyweight of the European economy, and China’s top trading partner within the EU. Scholz focused more on the economy than on the complex strategic issues stemming from a China that is increasingly aggressive in its region. Fresh off his conversation with Germany’s top leader, Xi Jinping will be able to leverage the competition between the EU’s two leading powers.

It’s large German companies like BASF that continue to invest heavily in China; according to figures from the European Chamber of Commerce in Beijing, the trend is toward disinvestment in European companies as a whole. It’s not hard to see why. The Chinese economy is not doing well; China is no longer the goose that laid the golden eggs, which once dazzled exporters and companies looking for fresh money. Xi’s touted new development model aims to replace persistently low household consumption with a shift toward a high-tech economy, essentially exporting massive surpluses from the Chinese automobile industry, solar panels, and more broadly, green technologies.

It is also within this framework that the visit to Paris takes place. Beijing hopes to mitigate the consequences of France’s posture on the trade deficit issue with China and on Beijing’s harmful commercial practices in sectors as essential to the French economy as the automotive industry. On these points, Xi expects concessions, but it is not certain that he will receive them; the social stakes of deindustrialization are too high for Paris to yield without effective reciprocity. “Economic security,” another term for denouncing excessive dependence on Chinese imports of sensitive materials, also weighs on France’s position and does not favor Chinese interests.

But history will also loom large. For Chinese leaders, the golden age of Franco-Chinese relations was the era of General de Gaulle, which is understood by Beijing through a simplistic lens of “anti-Americanism.” Dividing to rule is at the heart of Chinese strategic thinking. However, the strategic balances are no longer those of 1964.

China, despite its difficulties, is a behemoth that other countries all too often seek to accommodate in the name of often illusory common interests. It accounts for over 18 percent of the global economy, still driving growth in Asia and the African continent. Strategically, China is multiplying tensions using gray zone tactics, to which it is difficult to respond. In the South China Sea, serious incidents are increasing with the Philippines, which has drawn closer to the United States. Chinese pressure is also constant regarding its maritime dispute with Japan. China is a disruptor, sometimes playing for appeasement when its tactical calculations and interests demand it; seemingly positive developments in relations must always be approached with caution.

For its part, Paris may not have given up its hopes of seeing Xi Jinping use this visit to commit to playing a more significant role in favor of disengagement by Russia in Ukraine. Nothing is less certain. The current situation suits Beijing, which prudently remains on a razor’s edge. It enjoys all the benefits of a weakened Russia, captive to its Chinese client and forced to sell gas 30 percent below market price. China also is helping forge united front of autocracies, ostensibly offering an alternative to the so called Global South against the universalism of Western democratic values. And despite all this, China is also being courted to solve a problem once more – even though on other global issues, whether the denuclearization of North Korea or even on climate change, China has never demonstrated that it is ready to act beyond a engaging dialogue that merely recognizes its influence.

On the European side, the division of Europe, including on the Ukrainian issue, also allows China to demonstrate that it still has allies there despite the deterioration of its image across the continent. This is how the visits to Hungary and Serbia, after the French celebrations, should be understood. Xi’s trips to Belgrade and Budapest better demonstrate where Beijing’s priorities and true allies lie.

The challenge for Paris will therefore be to try to give meaning to a visit that doesn’t really have a very deep one. It is with one voice, and notably with Germany, that the European Union should speak to Beijing. It is far from certain that giving China’s top leader, especially after the tragic ideological crackdown in Hong Kong, an opportunity to regain a semblance of international legitimacy, while also benefiting from a too-flattering contrast with the pariah status of Vladimir Putin, is the best strategy for either France or Europe as a whole.