In the first week of June 2024, locals in the remote Tangi Shadan village of Allahyar district of Afghanistan’s Ghor province discovered the bodies of a 45-year-old widow and her 7-year-old granddaughter. Both had disappeared about two months earlier and are believed to have been killed for their property by men close to Mawlawi Jaber, the Taliban district governor. As her relatives approached the local Taliban office, the governor reportedly asked for the reason for a widow living without remarrying.

In the second week of June, Taliban Supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada issued a decree capping salaries of all female employees in all government as well as non-government sectors, irrespective of the nature of their work, experience, and seniority, at 5,000 Afghanis (around $70) per month, starting from June 2024. That’s the lowest level of salary in the Taliban’s government structure. The Taliban’s administrative office confirmed this absurd and blatantly discriminatory policy. In a country where finding employment is a huge challenge, this reinforces “working poverty,” when even individuals who are employed are nevertheless incapable of taking care of their dependents.

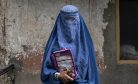

These are two examples of the widespread systematic repression that girls and women have come to endure since the Taliban took over power in August 2021.

The Taliban regime is headed by an obscurantist individual who appears to have no respect for women’s rights. Worse still, he faces little challenge within an organization that functions on the principle of loyalty, conformity, and deference. Since none of his policies appear to have been effectively challenged internally, it is almost certain that these are part of the organization’s governing principles and are unlikely to change significantly even if the top leadership changes. Akhundzada’s decrees have empowered Taliban middle-ranked officials as well as lower-rung foot soldiers to violate women’s rights with impunity. That has frequently resulted in incidents like the one that took place in Ghor.

While the broad trends regarding the plight of girls and women in Afghanistan under the Taliban have occasionally caught the attention of the international media, with most Afghan media forced to either comply with the regime or shut down, many incidents of abuse are never reported. Nevertheless, the latest report, released on June 10, by U.N. Women stated that the oppression experienced by women and girls in Afghanistan since the Taliban’s takeover is unprecedented in scale and generational impact. On June 13, a statement by Catherine Russell, UNICEF’s executive director, marked 1,000 days of girls being banned from attending secondary schools in Afghanistan. She said the impact of the ban can have “serious ramifications for Afghanistan’s economy and development trajectory.”

Alison Davidian, the U.N. Women Special Representative in Afghanistan, pointed to the extraordinary resilience demonstrated by Afghan women in the face of incredible challenges. She listed women who continue to run organizations, and businesses, and provide services. But resilience doesn’t come with a sure-shot element of permanence. It needs to be supported and nurtured.

“We must invest in their resilience. Afghanistan must remain high on the international agenda,” Davidian said.

A recent interview in The Diplomat highlighted Afghan journalist Zahra Joya, who founded Rukhshana Media in 2020, which provides crucial feminist perspectives on the developments in Afghanistan. In one of their recently filed stories, Rukhshana Media detailed how unceasing Taliban repression is impacting the profitability of female-led businesses in Badakhshan.

It is therefore important to ask two pertinent questions: Without significant external assistance, how long can such resilience, especially by those who are located within the country, last? And what more can be done beyond periodic reports by U.N. agencies that highlight the diminished women’s rights in the country?

Despite the impressive work by UNICEF as it continues to support 2.7 million children in primary education, running community-based education classes for 600,000 children, two-thirds of whom are girls, and training teachers, the U.N. and its members have been at fault for failing on at least two accounts. First, there is no unified push to expedite efforts to criminalize gender apartheid. It needs to be explicitly codified in international law. Second, the U.N. has not implemented the Security Council’s resolution 2721 (2023) on appointing a special envoy, despite six months having passed since its issuance on December 29, 2023.

A part of the existing problem could also be rooted in the approach of the regional countries, which have queued up to do business with the Islamic Emirate. It is useful to ask: when was the last time an important official of a regional country directly raised the question of women’s rights in Afghanistan? Is it possible to establish a link between the hardening of the Taliban’s posture on women’s rights with the increasing desperation of the regional countries to engage the regime?

In today’s circumstances, the regional powers, compared to the far-off West, potentially wield tremendous influence on the Taliban. But their impetuosity to secure their own interests in Afghanistan has led to a meek surrender of such leverage. The Taliban certainly need to be engaged. But an important principle of this engagement process needs to have the intent and vision to bring about change the Taliban’s discriminatory policies, not endorse them.