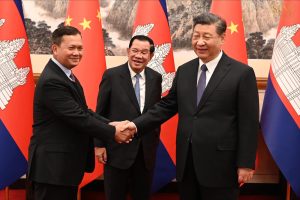

U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin is glad-handing in Phnom Penh this week, in what can only be seen as a desperate bid by Washington to draw Cambodia out of Beijing’s orbit. Such a move is aligned with the much-touted “window of opportunity” U.S. policymakers perceive with the dynastic succession of Prime Minister Hun Manet last year. Yet, a deeper look suggests that this bid (and the broader agenda behind it) was misguided from the outset.

The Hun Manet honeymoon has been an unmitigated disaster for U.S. foreign policy objectives. Symbolically, it is particularly poignant that Austin’s visit coincides with the christening of Xi Jinping Boulevard in Phnom Penh and the embarrassing departure of U.S. Ambassador Patrick Murphy. For weeks, media aligned with the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) have been effusive in their praise of Murphy’s sycophancy, while simultaneously slamming the U.S. government writ large. Throughout his tenure, Murphy proved a willing advocate for the regime, focusing primarily on public diplomacy gimmicks while failing, for years, to highlight the severity of Cambodia’s exploding scam industry or to raise more than perfunctory concerns about the regime’s myriad other abuses. The recognition he is now receiving duly indicates how well he served CPP interests, if not Washington’s.

More broadly, the softer U.S. foreign policy approach to the Kingdom of recent years has yielded a litany of failures. The current pro-engagement strategy has demonstrated a complete inability to shift Cambodia’s decidedly pro-Beijing domestic and foreign policy preferences. Moreover, the CPP appears to have lost all respect for Washington’s rights-based agenda. In the last half decade, just three members of Cambodia’s venal and predatory elite have been recognized with U.S. sanctions (all of them related to developments at Ream Naval Base). During that period, the Kingdom has plummeted into a prolonged era of political, labor, and environmental rights backsliding. Notably, these disturbing trends have intensified, not ameliorated during the Manet era, his West Point credentials notwithstanding.

Yet, the answer here is not merely to put away the Patrick Murphy-shaped public diplomacy carrot and replace it with a Robert Forden-shaped China hawk stick. What is needed is: 1) a full reconceptualization of what precisely Cambodia is, and then; 2) the fortitude to respond accordingly with the desired ends in mind. To the latter, yes, more serious diplomatic leadership will help. To the former, no, Cambodia isn’t just a Chinese neo-colony. Nor is it merely another authoritarian rights abusing regime clinging to Beijing’s guilt-free cash. It is both of these things, but it is also something far more complex and malign. That complexity and malignity demands respect and a credible diagnosis.

To get beyond outmoded and binary views of Cambodia, it is crucial to look beneath the geopolitical surface. Regime analysts have long deployed the term “shadow government” to refer to the web of elite power players, nepotistic entanglements, and corrupt mechanisms of influence that underpin Cambodia’s political economy. As in many highly corrupted countries, this system efficiently enriches and legitimizes the most powerful ruling elites and reliably ensures their continued political-economic dominance. Yet, Cambodia’s key distinction is that its elites have largely failed to diversify their economic interests beyond the extractive and illicit.

The CPP has proven itself a high-agency, dynamic actor playing the world’s powers to its benefit. Yet its dynamism is rooted in its state-institutional criminality and a pragmatic willingness to use state violence to defend elite criminal profits.

Conservative estimates suggest that elite-backed drug cultivation/trafficking, the illegal timber trade, and illicit sand dredging account for a plurality of total economic output. Moreover, Cambodia’s more licit industries – land speculation, construction material development, and agricultural production – are intimately tied to industrial scale money laundering and/or riddled with evidence of state-protected rights and labor abuse.

While miscalculations regarding the innately criminal nature of this regime have long plagued foreign policy efforts aimed at Cambodia during its nearly four decades under Hun Sen, Hun Manet’s father, (and make no mistake, Hun Sen is still running this sovereign criminal endeavor), the stakes are now higher than ever.

According to recent estimates from the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime and the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP), Cambodia plays host to perhaps the world’s largest epidemic of state-protected organized crime. USIP described “top to bottom state involvement” in criminal scam operations, which are valued at over half the annual GDP. It identified fraud compounds owned by cabinet-level officials, personal advisers, and family members of the prime minister. With over 100,000 trafficked victims trapped in these scam sweatshops and billions leaving the pockets of victims in the U.S. and elsewhere, the global human security threat is staggering.

Even from a strictly pragmatic perspective, deprioritizing a response to contemporary CPP criminality is a massive strategic blunder for Washington. Using best-available estimates, China likely invested over $12 billion into the Kingdom during the 10-year period from 2011 to 2021. These financial flows, so the U.S. policy narrative goes, have purchased Beijing undue influence over Cambodia’s voting patterns and domestic investment preferences. Yet, such largesse appears downright modest beside the $12 billion-plus being generated annually by Cambodia’s elite-captured scam industry. Of note to Washington, that industry was catalyzed by a small set of opaque China-originating criminal investors who now wield potentially existential influence over the highest levels of the Cambodian government.

Despite zero mention of the scam industry in Austin’s visit brief, there’s a strong case that this is the top U.S. national security issue in Cambodia, if not the greater subregion. Put aside for a moment concern about the CPP’s documented role as willing co-conspirator to Chinese-originating super-criminals. If the U.S. government merely hopes to claw back some of Cambodia’s effective Chinese proxy vote at regional and global forums, jeopardize China’s monopoly over its favorite new deep-water seaport in Sihanoukville, and/or derail the damaging, Beijing-funded Funan Techo Canal project, it needs to take a very different tact.

Beijing hasn’t won influence over this mafia state by wheeling out top brass as legitimacy-buttressing carrots or deploying ambassadors to take part in sarong singalongs. Rather, they’ve spoken in the only language that resonates with unaccountable, abusive criminals: cash and coercion.

To counter Beijing’s multi-pronged enablement of CPP kleptocracy, Washington will need to bring back the stick. Disincentivizing state-run criminal profiteering is the only option left for the U.S. to regain the respect of the regime or to reverse some of its foreign policy losses of recent years. This will look like a heavy dose of surgically targeted sanctions at known crime bosses and corrupt officials – and corresponding heavy investment in monitoring the broader network of elite Cambodian criminal actors. It will involve U.S. government advocacy for Cambodia’s re-listing on the Financial Action Task Force’s AML blacklist, which will limit the CPP’s use of the global financial system to bolster an economy built on money laundering and criminal activity. It will require a clear spoken message from Washington backed up by actions that demonstrate that the U.S. foreign policy community is no longer deluded about a “Hun Manet window of opportunity.”

Barring such a radical course correction, the U.S. will continue to fall short in its foreign policy aims for Cambodia – and the world will continue to suffer the consequences.