Wandering around Taipei last week there was a noticeable distinction between the media commentary on the prospect of an invasion of Taiwan by China and the apparent conditions on the ground. Despite the frequent incursions into Taiwan’s airspace by People’s Liberation Army aircraft, the Taiwanese go about their daily lives in a similar fashion to the citizens of any prosperous liberal democracy. Yet this is not complacency, it is defiance. To allow the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) threats to alter their behavior would give it a mental victory. Embracing and enjoying Taiwan’s freedom is, in itself, resistance to the CCP.

For Australia, maintaining this normalcy is a vital national concern. Not only because the Taiwanese people having the right to live free from invasion and subjugation is a moral imperative, but because the bulk of Australia’s trade is in the northeast Asian region, and any disruption to the sea lines of communication from a conflict in the Taiwan Strait would be devastating to Australia’s economy.

Australia’s approach to this situation is to form part of a coalition of other states that signal – increasingly with less ambiguity – that any attempt by Beijing to invade Taiwan would come with a mammoth cost to itself. However, deterrence is more complex than just military might. Economic interests are also central to creating a web of incentives for other countries to see their interests in Taiwan’s freedom and strong disincentives for Beijing to disturb the commerce that the CCP’s own legitimacy still relies on.

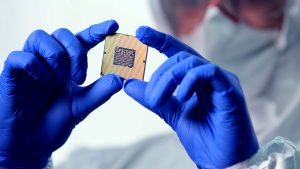

Central to this theory of deterrence is Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. Taiwan currently makes 60 percent of the world’s semiconductors and 90 percent of the most advanced chips, which power everything from consumer electronics to the most vital defense hardware. Taiwan’s indispensable position in the world’s modern economy has been described as its “Silicon Shield” – due to the crippling effects that would flow from the disruption of this industry. China itself would not be immune.

It is here that Australia also plays a role far greater than any contribution it may make to conventional military deterrence. Taiwan’s semiconductor industry requires a lot of power to operate. Its largest manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), consumes around 6 percent of Taiwan’s total energy consumption, meaning a steady and reliable source of energy is essential to its operations, and Taiwan’s economic and physical security. Yet Taiwan itself has only a limited capacity to produce energy itself.

Around 80 percent of Taiwan’s energy comes from fossil fuels, all of which is imported. Australia is currently Taiwan’s largest supplier of this energy. It contributes around half of its consumption of coal and around 40 percent of liquified natural gas (LNG). Australia effectively powers Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, and, in turn, powers its Silicon Shield.

This reliance on Australia’s energy imports may increase, as the administration of President Lai Ching-te looks to phase out the country’s nuclear power production, and green technologies struggle to gain significant traction. This lack of energy independence makes Taiwan more vulnerable to a Chinese blockade or quarantine. However, such a scenario is one that the Silicon Shield should in theory prevent from occurring.

However, the other threat to Taiwan comes from market incentives that may eat into its energy supplies. With China ending its restrictions on Australian coal and gas, producers in Australia now look to redirecting significant amounts of these commodities back toward China, and away from Taiwan, as well as Japan and South Korea. Were Australia to take Taiwan’s security seriously it may consider some quiet market interventions to make sure that these market incentives don’t undermine the more essential overarching commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Of course, the complicating factor in the relationship between Australia and Taiwan is not just China with its threats of invasion and massive market, but also climate change. Although coal and LNG remain central to energy generation worldwide – and massive export industries for Australia – they are both marked for decline as the world eventually transitions to cleaner forms of energy consumption.

Australia and Taiwan have been exploring a potential partnership in green hydrogen as a source of cleaner energy, but at the moment both the scale and cost of the fuel is nowhere near making it a serious replacement for coal and LNG.

For now, it is Australia’s abundance of fossil fuels and Taiwan’s digital capabilities that are working in harmony to advance the freedom and prosperity that the Taiwanese people enjoy. This may be an inconvenient reality, but one that needs to be acknowledged. However, the responsibility to protect both regional peace and the environment – not to mention Australia’s fruitful relationship with Taiwan – relies on new forms of energy security being advanced.

Disclosure: The author’s travel to Taiwan was courtesy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan).