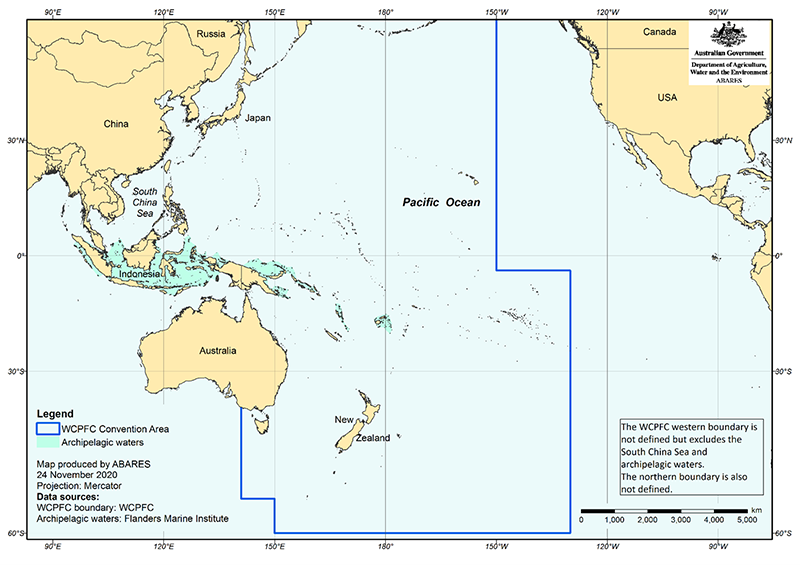

This year, for the first time ever, the People’s Republic of China registered 26 China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels to operate in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area. The Convention manages 20 percent of the globe, from the Aleutians in the North Pacific, all the way down to the Southern Ocean.

It is also the area of the First, Second, and Third Island Chains.

The CCG, widely used for gray-zone operations in disputed waters, will soon legally be allowed to board any foreign fishing vessels on the high seas in the First, Second, and Third Island Chains.

The area of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission. Map via the Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

Since 2020, China has also had four Coast Guard vessels registered to monitor foreign fishing vessels in the North Pacific Fishing Commission Area. Starting from June this year, China will have the third largest maritime security presence patrolling throughout the whole of the Pacific, after the United States and Australia.

The CCG is the maritime branch of the People’s Armed Police of China, which is led by the Central Military Commission of China. Its vessels are built to People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) specifications. The Coast Guard operates directly under the PLAN in a time of war.

In a steady process of attrition, Xi Jinping’s China is challenging the existing strategic order, and doing so through acts below the threshold of warfare.

China is using multiple channels, and notably dual-use military-civil activities, to normalize and legitimize its growing military and intelligence presence in the Pacific. China’s hybrid warfare activities are now the most significant traditional security threat in the Pacific. Xi has made it clear that Beijing does not share the values of the rules-based international order and has been telling the Chinese people to prepare for war.

For more than 70 years the sea lines of communication and chokepoints of the Pacific have been protected under the strategic denial policy of the United States and its regional security partners, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand.

The United States and its partners’ strategic denial set up was one of the lessons-learned recommendations after World War II. It is aimed to exclude adversaries that do not share the same security interests and values from establishing a military presence in the Pacific.

The inherent weakness of the policy has always been that the many small island developing states within the Pacific benefit from the security guarantee but have no alliance commitment to it. There is no military agreement that binds the Pacific island nations together, though the 2000 Biketawa and 2018 Boe Declarations state that any security challenges in the region should be dealt with collectively.

In the Xi Jinping era, China has aggressively targeted states along the First, Second and Third Island Chain with gray-zone activity, foreign interference, and repeated attempts to set up a China-centered security alliance for the region.

But China’s actions did not just begin when Xi came to power. For more than 24 years, the PLA has been providing in-depth training, doctrine, weapons, military vehicles and vessels, uniforms, and military buildings to the military forces of Tonga, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea. China’s domestic intelligence agency, the Ministry of Public Security, has signed secret cooperation agreements with police departments in Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, and Solomon Islands. PLAN vessels have been visiting the Pacific for 20 years for both military diplomacy and spying trips. The PLA is also accessing the Pacific by using PLA vessels and planes for humanitarian and disaster relief.

A global military power requires friendly ports, airfields, and satellite ground stations in foreign countries. From Kiribati to Vanuatu to French Polynesia, Beijing-connected companies have repeatedly tried to gain access to militarily significant airfields and ports. China has been thwarted in all those efforts.

Instead, over the last 10 years, funded by the Asian Development Bank and World Bank, China’s state-owned enterprises have built the bulk of all strategic airports, ports, and ring roads in the island developing nations of the Pacific.

China’s government sponsors foreign interference activities in every state and territory of the Pacific, which has a corrosive effect on local politics. That makes it hard for states to defend themselves against China’s malign activities that affect their sovereignty such as illegal, unreported, unregulated (IUU) fishing.

China’s distant-water fishing vessels without doubt the worst offenders for illegal fishing in the waters of the Pacific. For years China has been ranked by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime as the number one IUU fishing state in the world. China’s distant-water fishing fleet is also ranked the worst in the world for human trafficking. The Chinese industrial fishing vessel illegal drift nets kill everything in their path, leaving nothing for local fisher folk. Chinese government documents describe the foreign territorial waters and high seas these vessels operate in as China’s “distant water fisheries,” part of an entire industrial chain.

Within China’s distant-water fishing fleet hides a state-subsidized maritime militia, which works in tandem with the CCG and PLAN to haze and intimidate maritime states such as Vietnam and the Philippines over territorial disputes. The Biden administration have labelled China’s IUU fishing fleet, and their role as a maritime militia acting with with China’s maritime security forces, as a “national security concern.”

China’s aggressive gray-zone activities operate below the threshold of traditional warfare, making it difficult to get the political will for a coordinated response. However, the 2018 Boe Declaration redefined the concept of security in the Pacific region and highlighted the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of Pacific Island Forum Members.

Now is the time for its signatories, the developing island states of the Pacific, and Australia and New Zealand, to work collectively to face up to the challenge of China’s hybrid warfare in the Pacific, in the same way they are now working collectively to address the main nontraditional security challenge in the region, climate change.

The continued peace and security of the Pacific depends on it.