On June 25, the Legislative Chamber of Oliy Majlis reviewed a draft law to set fines for involving children in illegal religious education. There were no objections in the first reading of the draft.

If the amendments are passed, Article 47 of the Administrative Code (“Failure to fulfill obligations to raise and educate children”) will be updated to include fines for parents or legal guardians who illegally involve their children in religious education. The fines would range from 3.4 million to 5.1 million Uzbek soms ($270 – $404). For repeated offenses, the fine would increase to $670 or 15 days of jail time.

Last year, The Diplomat reported about the increasing numbers of hujras, clandestine religious classrooms, across the country. Parents, desperate for their children to receive an Islamic education – something they could not obtain under Soviet atheism or during the reign of first President Islam Karimov with tight government control over religious practices – now send their children to underground classrooms. Most teachers running hujras have limited formal religious education themselves and lack official licenses to teach Islam.

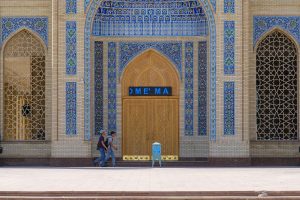

Uzbekistan is a Muslim-majority country, with 88-94 percent of its 37 million population following Islam. Despite this, there are only 15 educational institutions dedicated to teaching Islam. Thirteen of these are under the Muslim Board of Uzbekistan, comprising three higher education institutions and ten secondary education institutions (two of which are exclusively for girls). This number is strikingly small given the presence of 2,125 mosques across Uzbekistan, where Muslims pray five times daily.

Students can only be admitted to these institutions after graduating from secondary school, typically around 15-16 years old – an age considered too old for easy memorization of the Quran. In the Muslim tradition, the best time to memorize the Quran is childhood. But even at 16, getting into one of the religious education institutions is not for everyone. Because of the limited seats available, admission into these schools is highly competitive.

Studying Islam abroad as an alternative presents additional challenges. For many families, sending their children abroad is prohibitively expensive. Apart from that, many can study abroad only after turning 18. Since 2021, Egypt’s Al-Azhar University has required Uzbek citizens seeking religious education to have a recommendation from the Committee on Religious Affairs. This measure was implemented because many applicants, including Uzbeks, were using Al-Azhar as a pretext to obtain visas to Egypt and then study at other Islamic centers. An inquiry by the Uzbek Embassy in 2021 revealed that only 40 Uzbek citizens were studying at Al-Azhar, while over a thousand others were attending other study centers. There is a similar arrangement established between Uzbekistan and Saudi Arabia, and other countries too. Recommendations, however, are given only to citizens 18 or older, since secondary education is mandatory in Uzbekistan.

The call by the public and by the ulema (religious scholars) to lift the ban on private religious education has been constantly rebuffed. In 2021, the Committee on Religious Affairs issued three detailed letters stating that there is no urgent need for private religious education. Explaining that many parents want their children to be familiar with the everyday affairs of Islam, rather than seeking professional religious education in theology or academic education about religion in secular educational institutions, the committee argued that sufficient opportunities already exist – including 17 “Quran and Tajweed” courses to teach reading the Quran in three months, call centers, and different e-platforms to address any inquiries people might have about the Islamic lifestyle.

The committee also argued that adding Islamic classes within the mandatory state secondary education system obliges them to create the same opportunities for representatives of all faiths registered in Uzbekistan and this in turn might “cause various misunderstandings, disagreements, sedition and disagreements” in the Muslim majority country.

Addressing the same demands from the public, earlier Alisher Sa’dullayev, chairperson of the Youth Union of Uzbekistan, highlighted the lack of qualified professionals who could teach Islam properly. “There is a question of whether we have personnel who can teach this subject in a professional manner to the extent that it can be used for the purposes we want. We fail in the issue of whether the staff knows the subject in depth, whether they understand all the evidence and rules,” he said.

There is already an administrative punishment for those who provide a religious education without a permit from the Committee on Religious Affairs – a fine worth a couple of hundred dollars or up to 15 days of jail time. The draft law, if enacted, will extend punishment to parents who seek Islamic education for their children outside the limited opportunities legally available.