Proposed legislation in the U.S. seeking to combat transnational repression is a step forward in combatting the activities of regimes such as Cambodia’s, which routinely try to intimidate members of their diasporas.

The Transnational Repression Policy Act, introduced by Senator Jeff Merkley, would establish a transnational repression task force in the Department of Homeland Security to monitor intimidation by foreign governments of people in the U.S. and report annually to Congress. The bill needs to be combined with a comprehensive program of personal sanctions on those responsible for transnational repression, including asset freezes, to have the maximum effect.

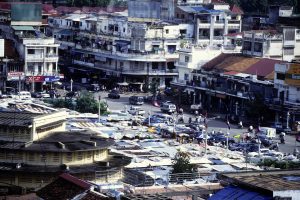

Cambodia has a long and well-documented record of transnational repression. Critics of the Hun family regime who have escaped to Thailand have been tracked down and beaten. As prime minister in 2018, Hun Sen made open threats of violence against Cambodians living in Australia. The widow of government critic Kem Ley, who was assassinated in broad daylight in Phnom Penh in July 2016, fled to Australia with their five children, and is among the Cambodians to have received death threats there.

When he visited Brussels in 2022, Hun Sen ordered his henchmen to take photos of protestors and put them on display at Phnom Penh International Airport. The families of the protestors could expect visits from the authorities, Hun Sen said. In the U.S., Cambodian journalist Taing Sarada is among those who have regularly received death threats.

Hun Sen stood down as prime minister in August 2023 and was replaced by his son Hun Manet. The change is purely cosmetic. Hun Sen still holds effective power as leader of the Senate and head of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). The pattern of intimidation inside and outside Cambodia has continued relentlessly under Hun Manet.

My own case highlights the way in which transnational repression is used by the regime. I was a supporter of the Sam Rainsy Party in Cambodia since 2002. The party merged with the Human Rights Party, led by Kem Sokha, in 2012 to establish Cambodia’s first united democratic opposition, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).

The CNRP won around 45 percent of the vote in both the national election of 2013 and the local election of 2017. The result in 2017 was in fact an improvement as the opposition had usually performed better in national than in local elections. The threat to the government that it would be defeated in the 2018 national election was clear. That led to the dissolution of the CNRP by the country’s politically controlled Supreme Court in November 2017.

By then, Kem Sokha had become leader of the CNRP and had been arrested two months prior. He is now serving a 27-year sentence having been convicted on a trumped-up charge of treason. Kem Sokha is detained at his home, unable to meet with even his medical doctors or lawyers without official approval.

I fled Cambodia in the wake of Kem Sokha’s arrest in 2017. I have no doubt that had I remained in Cambodia, I would have been either jailed or killed. Today, I live in Lyon, France, where I have been granted political asylum. I continue to criticize the regime through videos on my Facebook page, one of the few ways for Cambodians to openly discuss politics. My page has over 200,000 followers. The Khmer language media in Cambodia is overwhelmingly controlled by the government.

Even this kind of dissent in a far-off foreign country is possible only at a high price. My father is a military general, and supports the CPP. I have been disowned by my family. Hun Sen has publicly said that my family members may lose their jobs if I don’t keep quiet.

Such tactics show the basic cowardice of the regime, its refusal to engage in open, frank debate or even to allow dissenting voices to exist. Yet, due to the existence of the global Cambodian diaspora which in large part resulted from the horror of the Khmer Rouge years in the 1970s, those voices will always exist. The regime’s aim of zero dissent is strictly impossible to achieve. The Cambodian diaspora will always be grateful to countries worldwide that have hosted our nationals.

Yet those countries must not lose sight of the reality of the regime they are dealing with. The Cambodian government puts great emphasis on its national sovereignty and stresses that there should be no foreign political interference. Yet its transnational repression, which mimics the tactics of other repressive regimes such as China and Iran, undermines democratic sovereignty in free countries.

It’s urgent to do more to protect the freedoms of diasporas from authoritarian regimes that other citizens take for granted. A regime such as that in Cambodia which routinely seeks to intimidate members of its diaspora should be denied international legitimacy. Respect for dissenting voices outside and inside the country should be the minimum ticket for admission to the international fold.