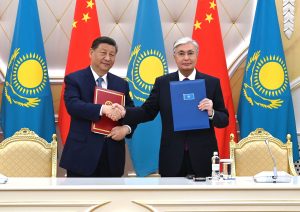

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Kazakhstan and participation in the 24th Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) on July 2-4, 2024, marked a significant shift in Central Asian geopolitics. The summit, which adopted the Astana Declaration and approved 25 strategic documents covering energy, security, trade, finance, and information security, underscored China’s growing influence in the region at Russia’s expense.

With every solar panel installed and wind turbine erected, China is not only reducing the region’s reliance on Russian gas but also drawing these countries into its orbit, securing its energy imports and cultivating a more favorable neighborhood.

Just a day before Xi’s visit to Kazakhstan, the State Council Information Office (SCIO) published an article highlighting the promising prospects for China-Central Asia green energy cooperation. It mentioned that Chinese companies like Goldwind Sci & Tech Co., Ltd. have made significant investments in the region, with Goldwind alone accumulating more than 319,000 kilowatts of wind power installed capacity in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other Central Asian countries by the end of the first quarter of 2024. The company also plans to invest in local manufacturing facilities for wind turbines in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, further deepening its presence in the region. The article further explained how Chinese enterprises have been instrumental in helping Central Asian countries transition to low-carbon production, with wind farms, hydropower stations, and photovoltaic power stations being built across Kazakhstan. The China-Central Asia Summit held in May 2023 had already paved the way for agreements on green development and climate change cooperation, and Xi’s visit built on this momentum by signing strategies for energy cooperation until 2030.

China’s investments in renewable energy in Central Asia can be divided into two distinct phases. From 1990 to 2018, China primarily focused on large hydropower projects in the region, leveraging its expertise and financial resources to develop this sector. However, from 2018 onward, there has been a notable shift toward solar and wind projects. This transition is marked by a change in the pattern of financing, moving from debt to equity financing, to address debt sustainability concerns and improve project viability in the region. The major drivers behind China’s growing renewable energy investments include Beijing’s desire to reduce supply chain vulnerabilities, particularly its reliance on seaborne LNG imports, and its aim to promote a “Green BRI” to bolster its international image. Notably, China’s approach to green energy investments is not uniform across Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In Kazakhstan, Chinese companies’ engagement in renewable energy projects has been primarily done through government-to-government agreements. In contrast, Uzbekistan’s renewable energy market has been more competitive, with Chinese companies entering the market mainly through tenders. As a result, Chinese firms in Kazakhstan primarily act as project developers, whereas in Uzbekistan, they often participate as EPC (engineering, procurement, and construction) contractors or input suppliers due to the presence of other international competitors such as ACWA or Masdar.

With Central Asia supplying over two-thirds of China’s pipeline gas imports in 2022, it’s no surprise that Beijing is increasingly viewing the region primarily through an energy lens. For example, the Central Asia-China pipeline network – consisting of Lines A, B, and C – has a total capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year, transporting natural gas from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan to China’s Xinjiang region. China’s growing reliance on Central Asian energy is further evidenced by its efforts to accelerate the construction of Line D, which would increase the network’s total annual capacity to 85 billion cubic meters (bcm). As China continues to prioritize energy security in the region, Central Asia’s role in powering its energy needs is poised to become even more crucial in the years to come.

In doing so, Beijing is steadily drawing the region into its orbit and away from Russia’s traditional sphere of influence. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal by Sha Hua also makes this case. The author argues that there is an evident shift in the economic landscape of countries like Uzbekistan, where Chinese vehicles from brands like BYD and Geely are increasingly replacing Russian Ladas on the roads. Also, Chinese investments are diverting the region’s young workers away from Russia. The numbers speak for themselves. Chinese exports to Kyrgyzstan surged from $7.5 billion in 2021 to nearly $20 billion in 2023, with much of those goods bound for Russia. In Kazakhstan, China accounted for 21.3 percent of the country’s total foreign trade in 2023, surpassing Russia’s share of 18.6 percent. Moreover, during Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s visit to Beijing in October 2023, Chinese and Kazakh companies signed 30 commercial documents worth $16.54 billion in oil, transport infrastructure, lines of credit, trade, and electric vehicles. China’s growing economic clout in Central Asia is not just about trade volumes. The BRI has made Kazakhstan an infrastructure hub for Eurasia, connecting China to Europe. Trade volumes between China and Europe via Central Asia have more than quadrupled.

However, China’s consolidation of influence in the region is not without challenges. Local resistance to Chinese dominance, competition from other powers like the EU and Gulf states, and the need to navigate complex regional dynamics all pose potential obstacles. Additionally, the revival of energy interdependence among Central Asian states, as evidenced by Tajikistan’s planned reconnection to the Central Asian Integrated Power System, may introduce new dynamics in regional cooperation.