There is a back-to-the-future atmosphere in the Pacific at present. Across the region, nations and territories are reckoning with history and its legacies as they try to forge a path forward in very uncertain times. Almost two months ago, the eruption of tensions in the French territory of New Caledonia shone a harsh light on French mismanagement of a delicate postcolonial political process. The deadly riots in Noumea that claimed their tenth casualty on July 10 erupted nearly two months earlier on May 13. The protests that began in May illuminated the longstanding struggles of Kanak people, who have been fighting the effects of more than 170 years of settler colonialism: minority status and the immense economic and social disparities that follow when Indigenous populations are forced to the margins in their ancestral lands.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s calling of snap legislative elections in June and July may have halted, for now, the French government’s contentious attempts to crush Kanak independence ambitions through legislation. These moves would have all but guaranteed an electoral minority status for the Kanak people.

Meanwhile, the far-reaching fallout from the deadly unrest is unfolding in France’s “dom tom” (department d’outre-mer) in ways sure to keep tensions, and the stakes in a future political resolution, high. The French use of textbook colonial tactics as a response to the riots, like the deployment of a massive force of 3,500 to secure the situation and the removal of five imprisoned independence leaders to France, are guaranteed to fuel discontent and elicit ongoing strong reactions throughout New Caledonia and the region because of how saturated such moves are with a bloody and brutal colonial past.

The outcome of France’s parliamentary elections, with the ultimate victory of the left-wing parties, does offer some hope for a retreat from Macron’s hardline, anachronistic approach to this crisis – one largely of his own making. For one of their two seats in the Paris-based parliament, New Caledonians, who turned out in high numbers, elected the son of the iconic figure of independence leader, Jean-Marie Tjibaou, who was assassinated at the height of the last eruption of turmoil in the 1980s. Emmanuel Tjibaou’s election halves the loyalist presence in Paris and it amplifies the echoes of the past that have resurfaced and continue to reverberate.

New Caledonia’s current struggles are a dramatic reminder of the quotidian legacies of colonialism in the Pacific that are dramatically shaping the present. These legacies impact the Pacific in multiple ways as the region grapples with the new challenges of climate change and the recent upsurge of geopolitical competition that is redrawing the geopolitical map.

This two-part series will cross the Pacific to locations where the convergence of historical legacies and present-day pressures are colliding and where changes to the status quo are in motion. It looks at some of the complicated connections and consequences of colonialism in the Pacific that provide both future burdens and opportunities for Pasifika people and the growing number of nations, like the United States, and institutions seeking to partner with this region during these times of escalating security concerns exacerbated by environmental challenges.

The Past Is Prologue

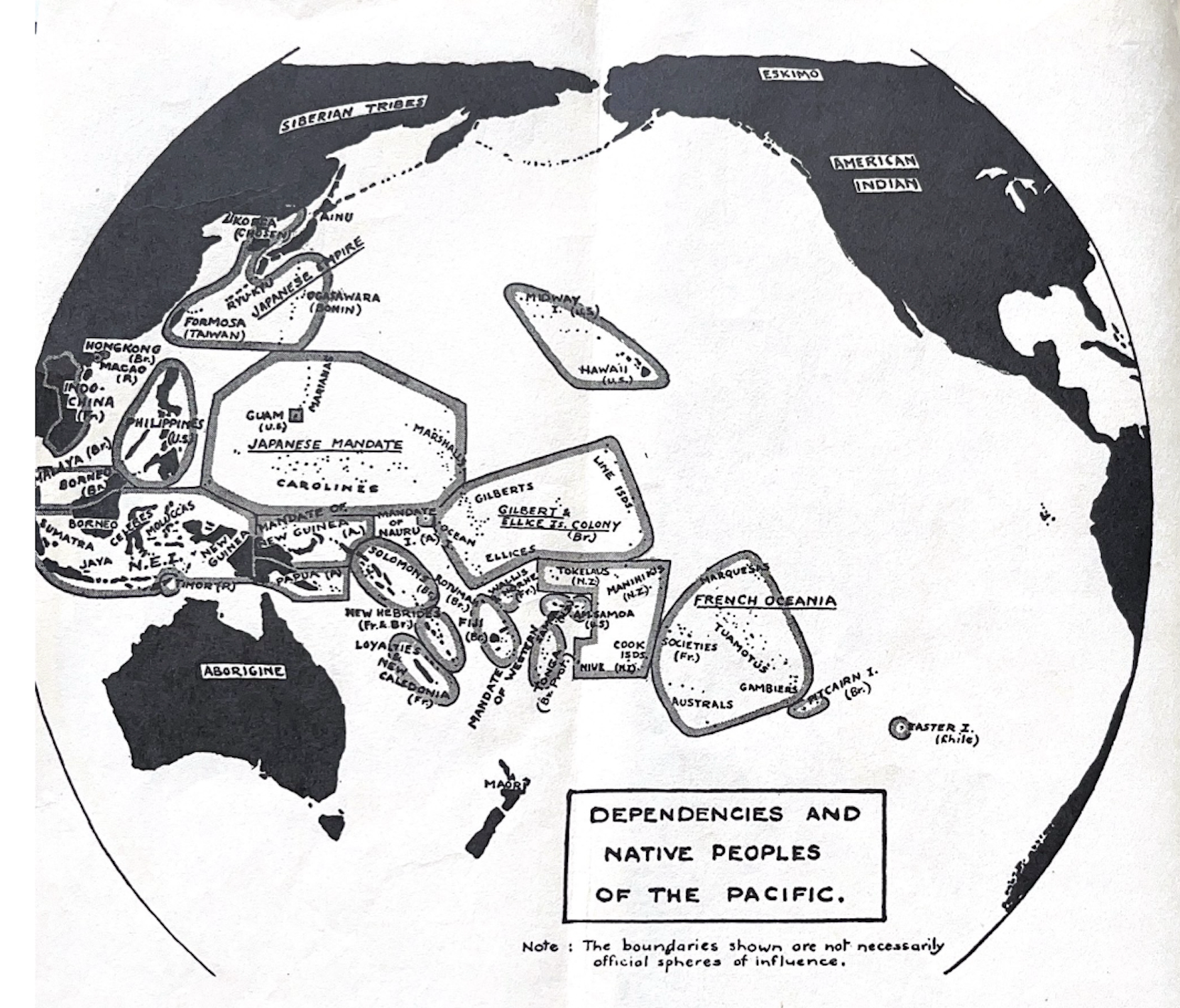

In 1931, two American anthropologists, Felix and Marie Keesing, attempted to condense the infinitely complex demographic landscape of the Pacific’s Indigenous people onto one map. This map was also a map of the empires operating in the region one decade before the Pacific theater of World War II erupted in 1941. The powers included the Netherlands, which had controlled the Dutch East Indies for centuries. Britain began building its Pacific empire out into the islands from 1788 when settlers first began colonizing what became known as Australia, and then New Zealand 50 years later in 1840. France began amassing its Pacific colonies, which remain virtually intact to the present, from its annexation of islands in Tahiti and the Marquesas in 1842, adding New Caledonia to its expansive imperial trove in 1853.

The 1931 Felix and Marie Keesing map, as it appeared in a draft conference report titled “Dependencies and Native Peoples of the Pacific.”

The Keesings’ map also included the “imperial burdens” Australia assumed in New Guinea and New Zealand in the Cook Islands, Niue, and Tokelau from Mother England once they became British Dominions in the early 20th century.

The map shows the expansion of United States territory into the Pacific as it stood in the 1930s. In addition to an array of uninhabited islands acquired under the 1856 Guano Islands Act (like Baker, Johnston and Midway), the U.S. annexed the Kingdom of Hawai’i in 1899, captured Guam and the Philippines in 1898 from Spain, and American Samoa in 1899 when the Samoan islands were partitioned in an imperial deal that gave Germany the western islands.

Germany already had substantial colonies in New Guinea and the Micronesian islands, all of which were stripped in the first weeks of World War I in 1914. New Zealand gained Western Samoa, Australia gained German New Guinea to add to its Papua Territory, and Japan gained all the German islands north of the equator. At the war’s end, these territories became League of Nations Mandates and then U.N. Trust Territories from 1947.

The Keesings’ 1931 map shows how imperial powers carved up the entire region, though Indigenous governing systems prevailed to varying degrees in spite of the imperial governing overlay that dominated this map. In Tonga, Indigenous rulers were not overthrown, though its ruling monarchy entered into a protectorate agreement with Britain in 1900, as the Keesings also duly noted on their map.

After World War II, the Keesings’ map kept changing.

In 1947, Japan’s Micronesian islands became U.S.-controlled U.N. Trust Territories. Then from 1962 to 1985, changes came at a rapid pace. Over these 23 years, former British, Australian, and New Zealand colonies, territories, and U.N. Trust Territories, became the independent nations of Western Samoa (known since 1997 as Samoa), Fiji, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, and Nauru, while the former single colonial entity of the Caroline and Ellice Islands became Kiribati and Tuvalu. All retained ties to Britain by becoming members of the British Commonwealth, even if they opted to have their own head of state, like Samoa, rather than the British monarch, like Papua New Guinea did in 1975 when it became independent from Australia.

For the rest of the Pacific, the post-war decolonial era was perhaps even more complicated. After Samoa became the first independent nation in the region in 1962, New Zealand devised an alternative model to keep the Cook Islands colony in its fold. These islands became a “realm state” freely associated with New Zealand in 1965. Cook Islanders could govern themselves while New Zealand would manage defense and foreign relations matters and bestow New Zealand citizenship, allowing for the circulation of people within “greater New Zealand.” A modified version of this arrangement was crafted for Niue in 1974, while Tokelau remains a territory in the Realm of New Zealand.

When the U.S. and its Trust Territories in the Pacific were devising a decolonization path in the 1960s and 1970s, the Cook Islands-New Zealand model was at the center of discussions. Yet three of the four regions – the Marshall Islands, the four island groups (Chuuk, Yap, Pohnpei, and Kosrae) that formed the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau – all opted for a different version of “free association” with the United States. This entailed national sovereignty, while the U.S. retained exclusive military access to their exclusive economic zones and their citizens gained rights to live and work in the U.S., sparking the beginning of “compact” migrations into the U.S. once these agreements first became law in the 1980s.

The Northern Marianas, the fourth component of the U.S. U.N. Trust Territories, instead opted to become a U.S. territory in 1978 with U.S. citizenship rights extended in 1986, similar to rights granted to the Chamorro of Guam in 1950.

American Samoans are instead U.S. nationals, a subject that spurred legal challenges which reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2022, though the court declined to hear the case brought by three Utah-based American Samoans. For American Samoa to become an “incorporated” territory, and so gain U.S. citizenship, the traditional political system that greatly privileges the chiefly (matai) social echelons would have to be abandoned. That continues to be a bridge too far for the territory’s leadership.

The map of the Pacific remained more or less static from 1985 when Palau became the last nation to enter into its era of independence while remaining freely associated with the United States. The mid-1980s was also when New Caledonia was last aflame with pressure to break with France, though this outcome was averted for 40 years until the détente forged then began unraveling from December 2021 thanks to French tactics.

In 2024, it is not only New Caledonia where there are pressures to once again redraw the Pacific map. Whether through rising waters, the results of conflict, political maneuvering, the movement of people, or the rapidly changing security architecture spurred by the rise of China, the map of the Pacific is once again potentially in flux.

Where are these pressures, why have they emerged, and why now? What are the paths ahead? These questions will be answered in the second part of this series.