Disputes over territory are perhaps the largest contributors to interstate conflict, as the recent examples of the Israel-Palestine and Russia-Ukraine conflicts have evidenced. The most insurmountable entry in this category, at least in terms of the length of the disputed boundary, is the 2,100-mile long disputed Sino-Indian border.

But boundary disputes of such magnitude are not set in stone, either. Just as the ebbs and flows of the China-India rivalry over the years have proffered moments of tension and war, they have also created opportunities for political entrepreneurs to craft détentes – and occasionally, even consider the possibility of a settlement.

The use of territorial swaps to settle boundary disputes is assumed to be taboo, owing to the immutable properties of a state’s territorial holdings. Domestic publics generally view any compromise of a state’s territory as a surrender of national prestige, ideology, and even the nation’s raison d’etre. However, in certain moments, such concessions are proposed and seriously deliberated upon. Two such moments took place in Sino-Indian relations in the Nehru-Zhou and Rajiv-Deng periods.

This is unsurprising if one considers the larger historical register. Despite a significant number of outstanding territorial claims, China has also resolved boundary disputes with neighboring countries such as Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. India too has resolved its share of boundary disputes, most notably through the exchange of enclaves with Bangladesh in 2015.

The two Himalayan rivals came close to a “package deal” on the Sino-Indian border too (twice!), but the proposals did not materialize. Do these failed attempts offer hope for an eventual resolution or portend the inevitably ruinous future of diplomatic attempts to solve the issue?

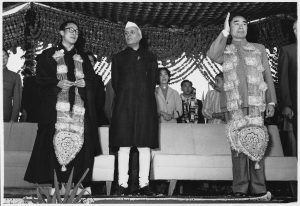

In 1960, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, accompanied by Foreign Minister Chen Yi and a 31-member Chinese delegation, arrived in Delhi to negotiate a final settlement of the disputed Sino-Indian boundary with his Indian counterpart, Jawaharlal Nehru. The boundary was a vestige of British colonial rule, and had been in dispute for longer than the existence of the Republic of India as well as the People’s Republic of China.

The British Empire had purposefully maintained Tibet as a “buffer state.” This allowed them to claim territorial largesse when the need arose, while continuing to deny Britain’s great power competitors a foothold in the region. The British Empire could countenance such an expedient arrangement with the Chiang Kai-shek-led Nationalist China. But this would only hold aspirational value for an independent India faced with Communist China on its northeastern border. The Indians were mere spectators as the Chinese annexed Tibet in 1949, making the two postcolonial states neighbors on a historically contested and undemarcated border.

Both the Indians and the Chinese knew of the disputed nature of the border but neither side wanted to raise alarm until they had militarily secured their status and legitimacy in border areas. When the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” were chronicled through a bilateral trade treaty on India’s commercial rights in Tibet in 1954, Indian and Chinese interlocutors deliberately and carefully avoided mentioning any disputed parts as trade posts.

Isolated stand-offs in feeding pastures along the Himalayan border had also begun to creep up as early as 1954 in areas in the Central Sector such as Bara Hoti. Historically, these boundaries were highly fluid and had been used by agrarians on both sides. However, the imposition of nation-statehood now demanded territorial exclusivity. Despite this, both India and China did not choose to directly address the boundary issue, opting instead to build a stronger negotiating position before showing their hand.

However, their position was forced when the Tibetan Revolution broke out in 1957. People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces from China, chasing Tibetan rebels, entered disputed border areas, often provoking confrontations with Indian border patrols. Since there was no formal demarcation of the boundary, the armed forces of both sides found themselves in a highly unenviable situation.

In 1959, in the Western Sector (Aksai Chin Region), a clash at Kongka Pass led to the death of nine Indian soldiers – the first casualties of the Sino-Indian boundary dispute. This forced Nehru and Zhou’s hand. Leaving the boundary ambiguous was no longer tenable.

Meanwhile, Chinese conduct was being heavily criticized by Soviet Union. In a meeting on October 2, 1959, Nikita Khrushchev unequivocally asked Mao Zedong and Zhou to settle the dispute in order not to alienate India from the Communist bloc. Begrudgingly, the latter committed that they would respect the “McMahon Line” in the Eastern sector and soon bring the issue to an end.

In a nutshell, this was the “package deal” – a status quo solution. The Chinese would accept India’s claims in the Eastern Sector, which was more critical for the security of India’s Northeast, in exchange for Indian acceptance of Chinese sovereignty in the Western Sector of Aksai Chin, which was the region that housed the arterial road that connected Chinese forces to the Tibetan plateau via Xinjiang.

For his part, Nehru too had been preparing the grounds for this “package deal.” In Parliament, he repeatedly mentioned Aksai Chin as inhospitable terrain. This provided some defense for India’s inability to prevent Chinese encroachments. The Indian side had long been willing to trade Chinese presence in the Aksai Chin region for China’s formal recognition of the McMahon Line in the Eastern Sector.

However, public opinion in India would not countenance such a deal in 1960. The Chinese could navigate the pitfalls of public diplomacy over a complex border issue much better than the Indians. Once the death of Indian soldiers on the border, and the scale of Chinese territorial claims, became public knowledge, Nehru’s room for maneuver had diminished significantly. Accepting the status quo meant the vindication of Chinese aggression on India’s borders, and was thus considered intolerable.

Despite the Chinese being the militarily stronger power, they proposed the “package deal.” And despite this arrangement being acceptable to India’s political leadership earlier, it was declined as this simply could not be justified to the Indian people or Parliament. This is why the talks between Nehru and Zhou failed in 1960.

The “package deal” was revived in 1979, when Deng Xiaoping proposed it to then-Indian Minister of External Affairs Atal Bihari Vajpayee during his China tour. Once again, the proposal was rejected by the Indian side, as they continued to insist on a detailed historical study to resolve the border in each sector.

In 1986-87, the intractability of border talks eventually led to a military stand-off in the Sumdorong Chu Valley in the Eastern Sector. A weak coalition government led by Morarji Desai, which only lasted in office for two years, did not have the ability to push through such a settlement. The deal was offered to Desai’s successor and Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, in 1984. But her assassination curtailed any serious consideration.

The deal was offered once again by Deng to Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1988. Deng wanted India to make minor territorial concessions to the Chinese on the Eastern Sector for Beijing’s acceptance of the McMahon Line (which was to be renamed). Similarly, minor Chinese territorial concessions to India in the Western Sector would be offered for India’s acceptance of Chinese sovereignty in the Aksai Chin region.

Chinese Diplomat Yang Wenchang recounts the exchange as follows:

As a diplomat in late 1980s, I witnessed a chance to solve the problem with Prime Minister Rajiv and Deng, who was also a strong man. We do some compromise on west wing, you do some on the east wing, then we can have a new border. We offered, but Prime Minister Gandhi didn’t have a response. After that I felt very sad we lost the chance.

Rajiv Gandhi had the parliamentary mandate required to formalize a “package deal.” But he too chose not to jeopardize his political future, settling instead for confidence building measures on the border to ensure “peace and tranquility.”

Twice, political compulsions and domestic weaknesses have compelled Chinese leaders to offer a “package deal” to their Indian counterparts to settle the border once and for all. But in both cases, the pulls and pushes of parliamentary democracy in India have made “managing the dispute” more palatable than its resolution.

Now, the scales have changed significantly. At least since 2017, in light of China’s sustained economic growth and newfound military strength, especially relative to the Indian side, the Chinese no longer want a “package deal” solution based on the status quo. Instead, they have proposed a new “package deal” that disproportionately demands concessions from India in the Eastern Sector, particularly in the populated region of Tawang. While Deng’s proposal in the 1980s too required a concession in the Eastern Sector, this was relatively minor and was to be reciprocated by Chinese concessions in the Western Sector. If a much more favorable “package deal” couldn’t pass muster in the past, Xi Jinping’s new proposal is highly unlikely to do so.

But ultimately, it is in the interest of both states to achieve a final settlement of the border and some variation of the “package deal” is most likely to prove fruitful in this respect. Unlike Taiwan for China or Kashmir for India, the Sino-Indian boundary dispute does not concern key pillars of national identity. Neither do the concerned border territories offer any particular advantage in terms of natural resources or larger strategic advantages beyond the rivalry. Therefore, the revival of a package deal would be favorable to India’s growth prospects as well China’s global ambitions.

Until the conditions for such a solution are arrived at, China and India should find ways and means of enhancing other important aspects of their relationship and managing conflagrations at the border. More so than the South China Sea, it is the resolution of the Sino-Indian boundary dispute that will determine if “Asia” will be a term that geopolitical experts will use as a reference of power, or to signify an arena of unending conflict and violence in the emerging world order.

This essay was first published in the Asian Peace Programme (APP) webpage. The APP is housed in the National University of Singapore (NUS).