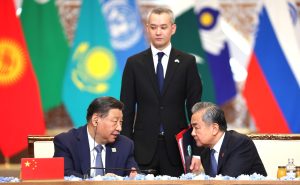

As the annual Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in July came to an end, questions about the futility of the organization remained. Initiated by China as the Shanghai Five in 1996, the organization for a long time included most Central Asian states plus Russia and China, before expanding to include India, Pakistan, and Iran.

This year the Council of the Heads of States issued a lengthy declaration, including pompous statements and listing the widest possible range of initiatives, agreements, and proposals addressing nearly all the areas of interaction among the member states and other international organization.

The big news was the accession of Russia’s staunch ally, Belarus. The grouping, once again, highlighted that its members constitute 40 percent of the global population, 80 percent of the Eurasian landmass, and a quarter of the global GDP – barely an achievement in itself.

The summit was snubbed by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, suggesting that not all is smooth sailing between India and its traditional adversaries, China and Pakistan. This undermines one of the SCO’s defining features as a body: demonstrating a united position for the non-Western, so called multipolar world order. The decade-old speculations that the SCO’s expansion outside of Central Asia would diminish its capacity have become more evident, but the SCO’s weakness lies not only in its lack of the geopolitical weight.

Within Central Asia, the SCO, despite multiple attempts, has failed to institutionalize cooperation in key areas like development, energy and free trade, largely because of Russia’s apprehension regarding China’s growing dominance in the region. The organization’s existing formal structures designed to develop some sort of uniform standards in banking, finance, and business transactions serve as networking forums at best. The core security institution, the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS), demonstrates functionality by organizing multilateral military exercises, but does very little to target terrorist organizations, considering that the expanded membership includes some of the main breeding grounds for terrorism – Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

In the words of one Eurasian expert, the SCO has turned into “empty shell unable to achieve tangible results aside from meetings and newspaper headlines.”

Arguably the, “golden age” of the SCO, which promoted security cooperation and gave Central Asian states a supposedly “equal” voice with their large and powerful neighbors, has passed. Comparing the SCO as a unique Eurasian organization to another unique and relatively successful institution, the Association of the South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), is no longer accurate. The SCO is better compared to the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), which held its last summit in 2015, but maintains a costly bureaucratic structure in one of the least integrated regions in the world.

Granted, compared to SAARC, which had one-third of its annual summits postponed for political reasons in its 30-year history, the SCO leaders have been meeting dutifully with proper pomp every year since the organization’s inception. Yet, failures to reach consensus on trade, energy, and water-sharing have marked both the SAARC and the SCO. Similarly, numerous agreements, such as the South Asian Free Trade Agreement, or the SCO Transport Agreement have been signed, but have not been properly implemented, as member states are prone to use non-tariff barriers or even shut their borders without any repercussions within the organization. Although the Southeast Asian states are not completely innocent of such actions, ASEAN has been much more successful in keeping the flow of goods and people moving.

These are measurable effects. Intraregional trade between ASEAN members has reached 25 percent, while intraregional trade in South Asia, despite a signed FTA, stood at mere 5 percent in 2023, a sad record considering the degree of complementarity of some of the South Asian economies. Central Asia, with single digit percentages of trade between regional states, is comparable, even though it does not have the dilemma of South Asia where India borders all the “smaller”’ states and none of them border each other. For Central Asia, the massive markets of neighboring major economies, and the direction of existing transportation and energy networks, historically directed toward Russia and the north, and more recently partly reformatted toward China, explain how Central Asian trade numbers with Russia, the European Union and China stand roughly at 30 percent each.

In recent years the trade between Central Asian states doubled, reaching $10 billion in 2022, but the SCO cannot be credited with this growth. Regional dynamics of economic cooperation have changed. During the COVID-19 pandemic trade with China slowed, even though growth has gotten back on track. Dealing with Russian has been complicated by the Western sanctions brought on by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Even though both Russia and China are top trade partners with all the Central Asian states, recent cooperative initiatives emerged from within the region, occasionally supported by actors other than Russia and China, particularly the aid agencies of the Western countries.

The cooperative dynamics among the Central Asian states, observable in recent years, have often been driven without the involvement of Russia or China. Uzbekistan’s opening up after a period of isolationism, the current Kazakh leadership’s traditional diplomatic style, and remerging dialogue between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are some of the factors accounting for enhanced cooperation in Central Asia. If anything, Russia and China often play a spoiler role for cooperation in Central Asia, not unlike that of India in South Asia.

There is a stark geographic difference, of course, with South Asia, where states do not border each other while they border India, which subsequently has control to facilitate or limit trans-border movements of people, goods, and energy. Even though Russia and China could be considered peripheral for Central Asia, the existing transportation and energy networks they control facilitate the flow of goods, services, and energy in their directions. The kind of seemingly irreconcilable rivalry witnessed between India and Pakistan is absent in Central Asia, but the shadow of Sino-Russian competition looms heavily.

Despite the “limitless partnership” rhetoric, Russia’s distrust of China and Russia’s ability to manipulate local regimes has stalled regional cooperation. Russia’s perception of the region as its sphere of influence prevented implementation of a regional free trade agreement, impeded fair competition in the energy field, and limited the extent to which China is able to use its economic prowess to complete projects of regional significance, such as the railway connecting China with Uzbekistan, through Kyrgyzstan, and an additional line of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline, which would require the cooperation of most of the Central Asian states.

As historic concerns about Chinese expansionism and the perception of Russia as a protector are increasingly questioned in light of Russia’s current aggressive foreign policy, it is of little surprise that Central Asian states are quietly revisiting home-grown regional cooperation, further marginalizing the institutional capacity of the SCO. After all, the Central Asian leaders have never really felt equal in the room with Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. In this sense, the dynamics of the SCO are more similar to that of SAARC, given India’s dominance, as opposed to the smooth-talking, consensus-seeking ASEAN way.

Both Central Asia and South Asia were wired for cooperation, but worked hard to sever the ties inherited from their respective Soviet and British empires, compared to ASEAN whose much more diverse membership often required building relationships from scratch. The founding members of ASEAN – Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand – had been parts of three different empires (except for Thailand, which was never colonized). They shared a common intention to resist the spread of communism, but when communist Vietnam joined, it became clear that ASEAN was able to put ideological differences to rest.

Ideology seems to be a peripheral issue within ASEAN. The ASEAN Way, with its focus on non-interference, ensured that democratic and autocratic regimes found ways to work with each other unless particular regimes were severely unstable, as in the cases of Cambodia and Myanmar, and ASEAN felt compelled to express concerns and create conditions for participation in the grouping. Multiple issues in Southeast Asia have been resolved, even though territorial disputes still exist among the members of ASEAN. The degrees of resolution vary widely, but, with rare exception, such as the Thailand-Cambodia conflict over Preah Vihear Temple, most do not flare up, and are generally addressed by the disputing and mediating parties without disrupting the institutional processes of ASEAN. The fact that no great power had strong and direct impact on the region did help.

In contrast, SAARC’s functioning has been completely disrupted whenever tensions between India and Pakistan resurfaced. The legacy of partition, rather than ideological differences, rendered SAARC dysfunctional.

Similarly, the legacy of the dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed traditional animosities in Central Asia to resurface. The dominant partners of the SCO, China and Russia, put up the facade of harmony, while the issues that mattered to Central Asian states, such as water-sharing or access to enclaves, were often swept under the carpet. Although the SCO intended to delineate the borders between China and the Central Asian states, territorial disputes between some of the Central Asian states continue to linger unresolved, occasionally flaring up, such as the border conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which resulted in deadly violence in 2021 and 2022.

With India and Pakistan’s accession to the SCO in 2017, the irreconcilable disagreements between the two, paired with the historic China-India rivalry added additional challenges. Instead of adopting lessons from continuous dialogue of the ASEAN Way, the Shanghai Spirit of “mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for diverse civilizations and pursuit of common development” is bound to be further diluted by the sulkiness of the subcontinent’s regional rivalries. But this lack of consensus, seemingly brought in by the South Asian rivals, is not new to the SCO. Disagreements between its two founding members, China and Russia, about the direction and the activities of the organization have existed from the early days. They have just been neatly swept under the carpet – one little gesture that does set the SCO apart from SAARC.