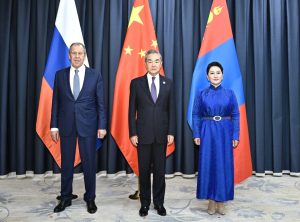

On July 3, Wang Yi, China’s top diplomat as director of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Foreign Affairs Commission Office and concurrently the foreign minister, presided over trilateral foreign ministers’ consultations with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Mongolian Foreign Minister Battsetseg Batmunkh. Meeting in Astana, Kazakhstan, on the sidelines of this year’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, the three ministers discussed trilateral cooperation issues. This is the first time that a trilateral foreign ministers’ meeting of China, Mongolia, and Russia has been held within the framework of the SCO.

This development can be interpreted in two very different ways. From one perspective, it’s a sign of strengthened relations, as the meeting between the foreign vice ministers of China, Mongolia, and Russia has been upgraded to the foreign minister level. From another perspective, however, the foreign ministers’ meeting is a downgrade from the summit mechanism between the heads of state of China, Mongolia, and Russia. The once-customary trilateral summit between China, Mongolia, and Russia on the sidelines of the SCO has not been held for two consecutive years.

The History of the China-Mongolia-Russia Trilateral

Looking at the modern history of the China-Mongolia-Russia trilateral, consultations or meetings between the diplomatic departments of Mongolia, China, and Russia at all levels first appeared in the mid-2000s, in response to the roll-out of Mongolia’s “third neighbor” foreign policy.

Specifically, in November 2005, U.S. President George W. Bush visited Mongolia. In response to the development of Mongolia-U.S. relations, Mongolia’s neighboring countries, Russia and China, jointly proposed the China-Mongolia-Russia trilateral mechanism. By 2007, consultations at the departmental level of the foreign ministries of China, Mongolia, and Russia had been held.

Trilateral contacts between the foreign ministries of Mongolia, China, and Russia continued to develop. After China’s President Xi Jinping and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin separately visited Ulaanbaatar in 2014, the trilateral mechanism was elevated to the level of deputy minister. The first trilateral vice foreign minister consultation between China, Russia, and Mongolia was held on October 30, 2014, in the capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar.

This consultation aims to implement the consensus reached at meetings of the heads of state of China, Mongolia and Russia, and promote the process of trilateral cooperation. In the past decade, meetings between the vice foreign ministers of China, Mongolia, and Russia have been held annually. Topics discussed included the medium- and long-term planning for the construction of the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor, the three countries’ highway and railway transport agreement, disaster prevention and control, and mutual assistance for the epidemic.

Last year, a new trilateral mechanism was established to deal specifically with security issues. The High Representative Meeting for Security Affairs of China, Russia, and Mongolia was held in Moscow, Russia on September 19, 2023. Wang Yi attended the meeting, as did Russia’s then-Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and the Secretary of the Mongolian National Security Council Jadamba Enkhbayar. There is even discussion of establishing a mechanism for trilateral meetings between the three defense ministries, or even future strategic dialogues (such as a vice ministerial level “2+2” or equivalent). These developments indicate that decision-makers in Russia and China are most concerned about cooperation and consultations with Mongolia in the fields of diplomacy and security, especially since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This year, Mongolia will host joint military exercises with its two neighboring countries in the north and south. In the first half of the year, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Ground Force and the Armed Forces of Mongolia jointly organized the first joint military exercise, Steppe Partner 2024, in Zuunbayan, Dornogovi Province, Mongolia.

In the second half of the year, the Selenga River 2024 joint Russian-Mongolian military exercise will be held on the occasion of celebrating the 85th anniversary of the victory in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol (also known as the Nomonhan Incident). The Russian side plans to deploy a detachment from the Eastern Military District to participate in the exercise. Since 2008, the Selenga River joint Russian-Mongolian military exercise has been held annually alternately in Russia and Mongolia. Last year, this exercise was held in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia.

Mongolia is located between China and Russia, with almost no terrorist activities within its borders. In addition, China-Russia relations are currently at the “highest level ever,” with close military exchanges and cooperation between the two countries, and there have been no military frictions along the border. So who are the “illegal armed groups” that China-Mongolia and Russia-Mongolia military exercises are targeting?

It’s not hard to figure out. In recent years, Mongolia has actively pursued a “third neighbor” foreign policy to overcome its geopolitical disadvantage of being landlocked between China and Russia. As part of that overarching policy, Mongolia conducts military exercises with the armies of countries such as the United States within its borders. Today, the current geopolitical environment has deteriorated, the political and economic and social environment in Russia and China is more uncertain, China and the United States are competing in every sphere, and the U.S. and its allies are explicitly backing Ukraine amid Russia’s ongoing invasion. In this case, China and Russia feel uneasy about expanding defense cooperation between Mongolia and the United States, or other partners.

Beyond the question of military exercises, Mongolia has also faced tremendous pressure and challenges from its neighbors in other ways. For example, in recent years, China and Russia have used various means to urge Mongolia to become a formal member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Mongolia was the SCO’s first observer state, but has refrained from becoming a full member even as the group rapidly expands.

Despite Mongolia’s non-membership in the SCO, the grouping’s annual summit has traditionally been fertile ground for China-Mongolia-Russia trilateral cooperation. In fact, the first trilateral leaders’ summit between China, Russia, and Mongolia, was held in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, on the sidelines of the SCO summit. All told, the trilateral summit has held six meetings alongside the Shanghai Cooperation Organization gathering. Former President Elbegdorj Tsakhia held three trilateral summit meetings during his term, former President Battulga Khaltmaa held two, and current Mongolian President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa has held one.

There are several reasons why Khurelsukh has attended fewer trilateral summits during his term. First, due to the impact of the COVID-19, the SCO summit in 2021 was hosted virtually. Last year, rotating SCO chair India again decided to hold the meeting through a video conference, precluding the possibility of sideline meetings.

The last trilateral summit – and the only one to date attended by Khurelsukh – was in 2022 in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, again on the sidelines of the SCO summit. At that meeting, the three parties reached an agreement to extend the “Plan on Establishing the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor” by five years. They also officially launched a feasibility study for the upgrading and development of the central line railway of the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor, and agreed to actively promote the “Power of Siberia 2” project, a China-Russia natural gas pipeline that will run through Mongolia.

In 2024, despite the presence of all three leaders – Khurelsukh, Putin, and Xi – in Astana for the SCO summit, there was no tripartite leaders’ summit.

Is China the Holdout?

On paper, 2024 should be a banner year for China-Mongolia ties, as it marks the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. Yet while Khurelsukh and Xi both attended the relevant SCO summit activities in Astana, there was no bilateral meeting between China and Mongolia this time – a very rare occurrence. The presidents of Mongolia and Russia, however, did hold a meeting. This suggests that the trilateral summit between China, Mongolia, and Russia was not held because of reticence on Beijing’s part.

There may be several reasons for this.

Firstly, China likely wants to avoid participating in large-scale projects between the three countries, such as the Power of Siberia 2, which would be bound to come up for discussion during a trilateral meeting. Last year, during Xi’s visit to Moscow, the two sides issued a joint statement specifically mentioning the three countries’ natural gas pipeline project. However, after Putin visited Beijing this May, the joint statement did not mention the Power of Siberia 2. It seems that Beijing is under pressure from various sides – public opinion on the domestic front, and sanctions internationally – to avoid some risks stemming from a new pipeline with Russia.

Second, in some areas China and Mongolia’s core interests are uncompromising and mutually damaging – especially when it comes to Mongolia’s Buddhist heritage. China does not want Ulaanbaatar to have any contact with the Dalai Lama, whom Beijing considers to be a separatist. In pursuit of that goal, many Mongolians suspect China of unduly interfering in Mongolia’s affairs.

In the first half of this year, local media in Mongolia exposed that the General Intelligence Agency of Mongolia had arrested three famous lamas from a Mongolian temple and a Chinese citizen (referred to by the surname as Hua or Huo by the media), who were suspected of engaging in espionage activities for China in Mongolia. The allegation of Mongolian temple lamas being manipulated by Chinese side once again makes the issue of China interfering in the search for the reincarnation of the 10th Jebtsundamba Khutughtu in Mongolia a focus of public opinion.

Third, China may not want to hold a trilateral summit unless and until Mongolia takes the plunge to officially join the SCO. Up to now, six trilateral summits at the SCO have been held within the past decade, even while Mongolian politicians have reiterated their position of maintaining observer status on multiple occasions, emphasizing the importance of their independent foreign policy and bilateral relations. After 20 years of Mongolia’s refusal to upgrade ties with the SCO, China and Russia may be growing frustrated. In that context, China’s abandonment of the trilateral summit – and refusal of a bilateral meeting as well – may be a strong signal from Beijing to Mongolia.

On this issue, Russia and China have different approaches. In May, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov emphasized that Russia believes Mongolia should become the next country to obtain formal membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. In Astana, Putin met with Khurelsukh to discuss bilateral cooperation. At the summit, Russia had constructive and positive discussions on cooperation with Mongolia, but remained firmly committed to making Mongolia an integral part and member of the SCO.

Whatever the reason, it appears that the trilateral mechanism between China, Mongolia, and Russia has been downgraded to the foreign ministers’ level. It may also take a different form in the future. Last year, Mongolian Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai proposed the establishment of a trilateral meeting mechanism between the Chinese, Mongolian, and Russian prime ministers at an SCO event in Kyrgyzstan. In February of this year, Russian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Rudenko Andrey Yurevich told local media that Russia welcomed the proposal and suggested that the “optimal venue” would be “the next meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Council of Heads of Government slated for Pakistan in the fall.”

Like many developing countries in Europe and Asia, Mongolia is facing pressure and competition in various fields between China and the United States, as well as the current dilemma caused by between Russia-Ukraine conflict. Geographically, Mongolia is adjacent to China and Russia, meaning the country benefits from their economic rise but also worries about their influence. Meanwhile, Ulaanbaatar has close relations with “third neighbors” and regards the United States, the European Union, and other countries as indispensable partners for cooperation and exchange. Against this backdrop, how to guide the development of the trilateral mechanism is a puzzle for Ulaanbaatar.

Another test for the trilateral is rapidly approaching as well: Next year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. On the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in 2015, China, Mongolia, and Russia held military parades together. Will 2025 bring a repeat of that show of unity?