Chinese President Xi Jinping once said that China “can only do well when the world is doing well… When China does well, the world will get even better.” His words highlight China’s view of its global significance and how its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) fits within the current world order. Over the past century, China has achieved rapid growth, especially since 1978, with the implementation of its reform and opening policies.

Colombia officially established diplomatic ties with China in 1980. Since then, China has grown into a crucial trading partner. The BRI, launched by Xi in 2013 in order to expand China’s global influence, has presented mixed success through its various public financing projects in the Global South. One of the best case studies of the BRI’s ups and downs is in Colombia, a traditional ally of the United States and a country with a history of conservative, anti-communist governments.

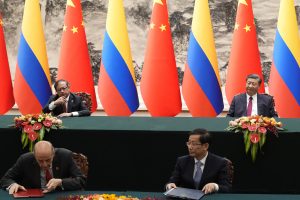

After electing its first left-wing president Gustavo Petro in 2022, that tide has shifted more rapidly, with China pursuing more aggressive projects and initiatives in the Andean country, and without controversy. Though Colombia has yet to join the BRI, the two countries enjoy a Strategic Partnership, signed in 2023, and China is now Colombia’s second-largest trade partner, and growing quite rapidly. “We view our future as a country that works with everyone, that collaborates with both the United States and China, we reject a Cold War framing of our diplomatic efforts,” a diplomat with the Petro administration said in Bogotá.

Colombia’s closer diplomatic ties with China are not necessarily new, however. Over the last few decades, many Colombian presidents have visited China, as did Petro in October of last year, and welcomed dignitaries from the People’s Republic. Colombia’s most conservative presidents of the last two decades, Álvaro Uribe and Iván Duque, also visited China.

Through these visits, Colombia and China have signed a variety of agreements and treaties, with China becoming an increasingly common source of financial support for energy, mining, infrastructure, telecommunication, and development initiatives. China has also opened a number of banking branches in the country and provided it with increasing legal and private tender reserves in yuan. Slowly, China has become a paramount economic and financial partner for Colombia.

During President Duque’s visit in 2019, the Colombian government launched the Colombia-China Initiative, a mechanism aimed at promoting the connectivity goals of the BRI without Colombia formally joining the initiative.

China’s efforts have mostly exploited basic gaps in the consumer markets and public necessities. Most of Colombia’s geography remains unconnected to any public road or telecommunication infrastructure; China has the capacity to reverse that trend. Given trade restrictions and difficulty accessing Colombian markets for foreign firms, telecommunications has been a source of financial strain for most Colombians in recent years. This has left room for Chinese state-affiliated companies like Huawei and ZTE to meet this need through various programs, including 5G service networks.

Water infrastructure, including running water and drinking water, has also been lacking in most of the country, particularly in coastal and remote areas, leaving China with an opening to provide financing for water access projects. Despite having two coasts on the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, Colombia also lacks the port infrastructure to become a larger commercial partner.

These needs are particularly acute in the Colombian Amazon, which remains very difficult to access and lacks basic government services and infrastructure. Finally, China has room to exploit the severe lack of structure and financing in the Colombian energy and mining industries. While Colombia is home to significant reserves of critical minerals and fossil fuels, lack of investment interest and lackluster government policies have made the sector difficult to navigate. Opportunities, however, have opened up for China to enter the field, in particular through the BRI’s multi-billion-dollar public investment program.

These needs have partially been met through Chinese investments. China is now the largest telecommunications and technological provider in the country, with around 35 percent of the market share according to September 2023 data. During Petro’s visit to China in October, new agreements on science and technology exchange were also signed, allowing for further market access for China.

POWERCHINA COLOMBIA S.A.S., a local subsidiary of POWERCHINA in Beijing, has been renovating two large water plants in Bogotá through these agreements, and China has contributed the primary financial stake in the Hidroituango dam, the largest hydroelectric dam in Colombia.

Chinese state corporations have also reportedly built water treatment plants in remote areas of the country. Beijing has also been looking to expand the Buenaventura port on Colombia’s Pacific coast, which would help bring in significant commerce and tourism, though the talks have not been transparent.

Furthermore, China has been financing massive infrastructure projects in Colombia, including the long-awaited Bogotá metro, extensions to the Medellín metro, the Trans-Amazonian Railway system, and the Mar 2 highway project in Antioquia and the Caribbean coast. China has been buying out struggling mining and energy projects throughout the country, most of which belonged to local and Western companies.

This includes the Continental Gold mine in Buriticá, which Zijin Mining bought for $900 million in 2019. China has also been acquiring a number of Canadian petroleum companies for billions of dollars, and starting fossil fuel projects with Colombia’s Ecopetrol. In addition to these critical sectors, China has been investing billions of dollars in agriculture, education, electricity, and other sectors to increase its influence and partnership with Colombia. The prospect of Colombia joining the BRI could make the pace of China’s investments rise significantly.

There are, still, significant problems and scandals surrounding China’s critical investments in Colombia. China’s human rights record, both at home and abroad, is appalling.

Through the influence acquired via the BRI, investigators have found that the Chinese government spies on Chinese nationals and uses its economic and political leverage to create harsher political climates and increase surveillance on Chinese nationals abroad. China’s state-backed Nickel hacking group is reported to work in Colombia, and the PRC also operates overseas policing stations and surveillance networks in neighboring Venezuela, Ecuador and Brazil. China’s governance preference for nationalist dictatorship also has significant ramifications for the future of democracy in Colombia.

There have also been accusations levied of untransparent business practices, overt mistreatment of non-Chinese workers, environmental damage, unethical negotiation tactics such as underbidding, and tensions with indigenous peoples.

These concerns can create tensions with the Colombian population, which has been reflected in polling, though most Colombians now say they welcome Chinese investment, even if they are wary of its culture and values. Moreover, the aggressive and secretive way in which China has conducted business has led to tensions with other business and strategic partners, including the United States. China has a lot of work to do to create a more open and receptive economic environment, and reassure critics of its intentions and objectives.

Colombia has traditionally relied on the United States for economic and strategic support. However, with the BRI driving growth in Asia and Africa, Colombia now confronts a difficult balancing act between its interests with the United States, and its growing partnership with China.

When the meeting between Petro and Xi in Beijing was announced, there was significant public enthusiasm for a potential agreement that would see concrete steps being made for Colombia to join the BRI. However, Petro asserted that Colombia should prioritize strengthening investment ties with countries that have a deeper understanding of its needs – a reference to China’s issues with integration, democracy, and human rights.

Moreover, as Colombia correspondent Santiago Torrado reported in El País in 2023, “Colombia is unprepared for the Chinese investment boom.” According to the focus and nature of President Petro’s meeting with his Chinese counterpart, the main topics on the table were purely diplomatic, specifically centered around the situation of the Bogotá metro. Therefore, it is understandable that for the Colombian government, relations with China and interests in the BRI are not considered short or medium-term priorities.

However, it is crucial for Colombia to recognize China not only as a global economic powerhouse but also as an example of resilience and success in overcoming significant challenges.

Like China did in its time, Colombia is facing uncertain prospects of outward growth and development, but through mutual understanding, educational cooperation, and joint efforts, the BRI could represent a concrete long-term goal for Colombia – one that promotes its economic recovery and future strength.