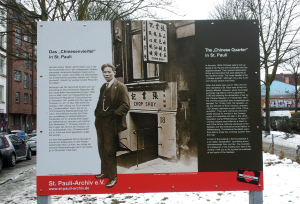

The echoes of a unique cultural history can still be felt through the Chinese community of Hamburg, which has grown significantly in recent years. This contemporary growth is rooted in a century-old history. In the 1920s, Hamburg’s Chinatown emerged on Schmuckstraße in the St. Pauli district, driven by Chinese sailors and traders who were attracted to the port city by economic opportunities and favorable exchange rates during Weimar Germany’s period of hyper-inflation.

Chinese migration to Germany began earlier, in the 1860s, when a few Chinese – including, decades later, future Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai – came to Germany to study at university. Germany’s Chinese population expanded from 43 people in 1903 to about 1,800 by 1935, with significant populations in both Hamburg and Berlin.

During the Weimar Republic (1918-1933), Germany’s cultural openness allowed the Chinese community to thrive, contributing to social and cultural life with establishments like “Cheong Shing” and the still operating “Hong Kong Bar“. Many Chinese residing in Germany at the time were ideologically left-wing, including notable figures like the revolutionary Xie Weijin.

The period of openness for the Chinese community in Germany ended with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. The Nazi regime began targeting political opponents, including Chinese individuals linked to communist or socialist groups. Notably, socialist activists like Chen Qiying were arrested and expelled for anti-state activities and Marxist affiliations.

Conditions for the Chinese community as a whole progressively worsened, leading many to be expelled or leave voluntarily. By 1942, all Chinese residents remaining in Berlin were interned in the Langer Morgen labor camp in Hamburg.

The persecution peaked with the “Chinesenaktion” (Chinese Action) on May 13, 1944, when the Gestapo raided Schmuckstraße, arresting around 130 Chinese individuals. Their passports, valuables, and money were confiscated, and they were severely abused and tortured in Fuhlsbüttel police prison before being moved in September to the Langer Morgen labor camp, where many perished. Many Chinese women were also detained, interrogated, and deported to concentration camps.

By the end of World War II, the Chinese community in Germany was nearly wiped out, with only about 30 individuals remaining in Hamburg. However, new Chinese migrants began arriving during the post-war period. In West Germany, the community grew slowly, reaching 2,500 people by 1967, many of them linked to the Kuomintang regime, which was overthrown by Mao Zedong’s communists in 1949.

The community struggled with its past, but efforts for reparations and recognition of their persecution were unsuccessful. Restitution offices and courts ruled that Gestapo actions were standard police procedures without racist motivations. As a result, Nazi persecution during the “Chinese Action” became a taboo subject within the post-war Chinese community.

Today, there are no more Chinatowns in Germany. However, the Chinese community has grown significantly in the 21st century due to strong Germany-China relations and increased trade and investment. Germany has become a favored destination for Chinese students, drawn by the country’s reputable and affordable higher education system.

Chinese culture is prominent in major German cities, with Chinese restaurants, markets, and academic institutions. The Chinese community, both Chinese citizens and those of Chinese descent, is estimated to exceed 300,000 people, with particularly large populations in Hamburg, Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, and the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan area. Some municipalities have established strong institutional and business ties with China, with Duisburg even proclaiming itself Germany’s “China city.”

Many Chinese students come to Germany to pursue degrees, particularly in STEM fields, and are welcomed by German universities and research institutions. However, the public perception of Chinese students has recently been affected by the growing geopolitical tensions between China and the West.

In a number of cases it has become clear that the Chinese government exercises a high degree of surveillance and control over the Chinese students in Germany. Many students are bound by contracts from the China Scholarship Council (CSC), which mandate loyalty to the Chinese state and discourage activities that might harm China’s interests. This could lead to a climate of fear and self-censorship among Chinese students at odds with Western ideas of academic freedom.

Starting in the 2020s, an intense debate emerged in Germany regarding the possible espionage threat posed by Chinese students. Students with CSC scholarships, in particular, are suspected of spying on German research institutions. This suspicion led the German Rectors’ Conference to propose banning the admission of Chinese students with CSC scholarships. In the current situation, increasingly Chinese students are falling under general suspicion. The issue was further exacerbated by the discovery of unofficial Chinese “police stations” operating in Germany.

Another significant recent issue is the smuggling and trafficking of Chinese nationals into Germany. In 2024, authorities exposed a luxury smuggling ring that charged wealthy Chinese individuals up to 360,000 euros to obtain residency illegally in Germany. The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated the existing racism and xenophobia towards the Chinese community in Germany, prompting incidents of verbal abuse and physical assaults.

Anti-Asian racism has deep roots in Germany, dating back to the German Empire’s portrayal of China as a “yellow threat,” and the persecution of the Chinese under Hitler. Current geopolitical tensions between Germany and China have further aggravated these issues, reinforcing historical biases and intensifying scrutiny of Chinese students and migrants, who are increasingly viewed as threats rather than community members.

Germany is often praised for its politics of remembrance, yet its treatment of the Chinese community reveals a significant lack of historical awareness and accountability. The success of Chinese restaurants since the 1960s has masked the dark history of persecution, leading to labels like “inconspicuous minority” for Chinese migrants, similar to the “model minority” stereotype that attaches to South Koreans. These labels overshadow lived experiences of racism and xenophobia, allowing the German majority to avoid confronting its past.

Only in the 1980s did Germany begin to acknowledge its past persecutions of the Chinese community. In Hamburg, a small memorial was erected in the late 1990s, replaced by a new one on Schmuckstraße in 2011, with 13 stumbling stones laid in 2019 for known Chinese victims. Several films and a 2018 exhibition also addressed the community’s fate during the Nazi regime. These efforts are only initial steps in Germany’s journey to confront its past. As the Chinese minority now faces intensified geopolitical tensions, enhancing the culture of remembrance is crucial to avoid repeating historical mistakes. Germany must not succumb to historical amnesia, even amidst the growing rivalry with China.