On November 9, 1799 – the 18th of Brumaire, according to the French Republican Calendar – Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in Paris, declaring himself the nation’s first consul and signaling the end of the French Revolution. Karl Marx later immortalized this event in his renowned essay, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon,” which popularized the oft-quoted refrain about history repeating itself, “first as tragedy, then as farce.” Since then, revolutionaries have feared the moment when a dictator emerges from within, and the revolution devours itself.

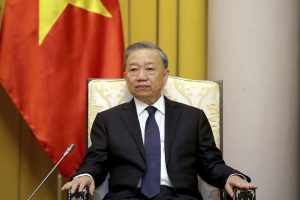

Had a coup occurred in Hanoi recently, it would presumably have not escaped our notice. The death of Nguyen Phu Trong, the Communist Party of Vietnam’s general secretary from 2011 until his passing last month, was mourned throughout Vietnam and reported widely. According to some observers, the swift appointment of President To Lam, a former Minister of Public Security, as Trong’s successor reflected a desire for continuity. The New York Times informed us this month that “there has long been a consensus about the need for stability through a power-sharing system that might prevent the rise of a single all-powerful leader.”

Such confidence is misplaced. Mere days after Trong’s death, Lam, the chief enforcer of Trong’s signature anti-corruption campaign, was quickly made the acting party chief before formally assuming the role on August 3. He will also continue to serve as state president, a position he acquired this year after ousting his predecessors.

Using Trong’s signature anti-corruption campaign, Lam and his allies have been systematically eliminating their rivals. Six members of the Politburo have been purged since early 2023. Lam loyalists, as well as generals from the police and military, have taken their place. For Bill Hayton, Vietnam is now a “literal police state.” Nguyen Khac Giang contends that there are now just two technocrats – National Assembly Chair Tran Thanh Man and Dinh Tien Dung, Hanoi’s party secretary – on the rejigged 16-member Politburo.

As Trong’s health deteriorated, Lam’s purge intensified. In March, then-President Vo Van Thuong, a possible successor to Trong, was forced to “resign.” (The following month, another Trong acolyte, Vuong Dinh Hue, was removed from his post as National Assembly chairman). The party convened in April to discuss Thuong’s replacement, with Lam positioning himself as the frontrunner. He officially assumed the role on May 18.

However, this left a vacancy in the Public Security Ministry, arguably the most powerful nowadays. Reports suggest there was significant infighting as some party members sought to appoint a new minister with no ties to Lam. Yet, he emerged victorious. On June 6, Lam’s deputy and childhood friend, Luong Tam Quang – his father reportedly served as the personal bodyguard of Lam’s father during the Vietnam War – was appointed to the position. Lam also secured the appointment of another ally from his home province, Nguyen Duy Ngoc, as head of the Central Committee Office, responsible for organizing party meetings.

There were rumors that Gen. Luong Cuong, the top political commissar of Vietnam’s armed forces, would take over the state presidency if Lam assumed the role of Communist Party chief. However, Lam quashed these plans, as well, and will now occupy two of the “four pillars” of Vietnamese politics. This concentration of power was prohibited by the party in the 1980s but was overturned by Trong in 2018 when he held both posts concurrently following the death of an incumbent president. At that time, concerns arose over whether Trong was becoming an all-powerful leader – a “paramount ruler,” which the Communist Party has historically tried to avoid. “Trong is the next Xi,” some began to speculate, referring to China’s supreme leader.

Yet, Trong was no dictator. Practically, he couldn’t have been. He relied on men like Lam, who knew where every other senior party leader stood and had the ability to bring them down, to carry out his directives. Institutionally, Trong did not control the Public Security Ministry, the police, or the military. He was more of a figurehead – an inspirational leader rather than a bureaucrat with knowledge of where bodies were buried or how to manipulate the system. To use a communist analogy, he was more Lenin than Stalin. Lam, however, has the potential to become the latter.

Moreover, for Trong, the anti-corruption campaign was not a cynical exercise in power accumulation. His family did not enrich themselves; his children did not become “princelings.” His funeral, solemnly held on July 26, was understated, with Trong carried in a plain wooden coffin. His vision was somewhat idealistic, rooted in a bygone era of Ho Chi Minh-style moralism and socialist principles. By 2016, when his “blazing furnace” campaign began, the party had become divided, corrupt, and individualistic.

However, as I recently wrote, Trong’s vision created the conditions for a dictatorial figure to succeed him. He eroded each of the checks the party had imposed to prevent a supreme leader figure from rising to the top, from a separation of powers between the top four jobs to retirement ages and term limits. Trong was the first general secretary since Le Duan to hold the post for three terms, creating a precedent To Lam will need. Moreover, to achieve his anti-corruption goals, Trong had to centralize power within the central party apparatus, weakening provincial party offices and government institutions. That is the only way to clean up an uncleanable organization, in which power flows up and discipline is enforced from above, in which “internal supervision” is the only possibility since there is no free press or popularly-elected leaders.

For Lam and others who fed the “blazing furnace” with sacrificial officials, anti-corruption was a means of self-advancement. Although he was Trong’s enforcer, Lam is no ideologue or moralist. Trong spent much of his life editing the party’s theoretical journal or chairing the Hanoi party committee and the National Assembly. To Lam, by contrast, has never stepped outside the national security apparatus – until now.

The party is now in the hands of “securocrats” from the police and military for the first time in decades. The ideological faction loyal to Trong has passed with him. The technocratic faction, which sees leadership as the duty of intellectuals, is terrified and cajoled. The “rent-seekers,” who saw corruption as a way of binding a disparate party together, have been utterly purged. The central party apparatus now holds more power than it has since the Đổi Mới reforms of 1986. Lam is busily installing his allies in provincial offices. While Vietnam is becoming a police state, the Communist Party is becoming a garrison institution.

Lam still has rivals, however. One is Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, but he has been weakened. One of Chinh’s deputy prime ministers has been ousted from the Central Committee, and another, Tran Hong Ha, may soon face the same fate. Chinh’s position is precarious as prosecutors investigate the corruption case involving the Advanced International Joint Stock Company and its fugitive chairwoman, Nguyen Thi Thanh Nhan, with whom Chinh allegedly has ties. If Chinh falls, Lam’s power will be nearly absolute.