On August 6, 2021, I awoke to a haunting truth: My dear friend and former colleague, Dawa Khan Menapal, was silenced forever. A dedicated journalist, he served as the deputy spokesman for Afghanistan’s last president, Ashraf Ghani, and was the head of the Afghan government’s Media and Information Center at the time of his assassination in the heart of Kabul.

As the Afghan government teetered on the precipice of collapse, Kabul transformed into a haunting tableau of high-profile killings. Many of the victims – government officials, journalists, religious figures – had well-known faces. The violence had entered a new and chilling phase: High-profile explosions had been supplanted by a wave of assassinations across the country, instilling a pervasive sense of fear. This shift not only heightened the tension in the streets of the Afghan capital, but also eroded the trust that many had placed in the Afghan security forces. The very fabric of society seemed to fray, as each shocking event further underscored the precariousness of life in a nation beset by turmoil.

Yet, I could never have imagined that Menapal would become one of the casualties. He was not the kind of man whose absence one could easily envision; his vibrant spirit seemed indomitable, a beacon of resilience that promised to persist even in the darkest of times.

From my family’s new home in the United States, we mourned in silence. We hardly spoke to each other. But to escape the heaviness, I went for long walks. I kept hearing Menapal’s voice.

I had a lot of questions and no answers. If the government was falling and the Taliban were returning to power without any guarantee of preserving the progress Afghanistan had made in two decades, then why all the sacrifices of the previous 20 years? Thousands of Afghans have lost their lives on the battlefield and in explosions, suicide attacks, and bombings. Menapal’s assassination struck deeply at my heart.

As I sat in a desolate forest, clutching my phone and listening to his voice messages, a profound wave of sorrow enveloped me, reminding me of the delicate threads that weave together the dreams of a war-torn Afghanistan.

“Cousin, bring me a good perfume when you come to Kabul next time,” he gushed, laughing, in the final message I would ever receive from him.

The next message was about an American journalist friend of mine planning to go to Kabul to write a story. She needed someone to help her, and Menapal volunteered: “Tell her she has a brother here who will take care of her.”

I kept listening to the messages he had sent me. When the phone eventually slipped from my grasp and landed in a stack of dried leaves, I didn’t have the power to bend and pick it up.

In the heart of Kabul, where the past and future constantly clash, Menapal stood as a symbol of hope and defiance. Born with little but dreams, he journeyed from a dusty village school to the corridors of Afghanistan’s presidential palace. His laughter, his unwavering belief in education, and his fearless journalism painted a vision of a prosperous Afghanistan.

He never said Kabul was unsafe; he refused to believe it.

His killing was not just a personal loss; it was a stark illustration of the relentless struggle for a brighter future in Afghanistan, a future that he tirelessly fought for but did not live to see.

My family became acquainted with Menapal through the stories I shared. Through my accounts, they traced his journey from a village in Shahjoy, a district in Zabul, one of Afghanistan’s most volatile and impoverished provinces, to the country’s presidential palace. His optimism was a source of inspiration for me. We cherished him for the songs he sang, the poetry he crafted, and the jokes he told – humor that I often relayed to my siblings to elicit their laughter. Yet, above all, my family held him in great affection because he was my friend – indeed, my oldest friend.

I first became acquainted with Menapal in 2005, at the outset of my journalism career. I had just joined Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, a media organization that broadcast news and information to Afghanistan from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. We had not yet met in person. He was a freelance reporter in Afghanistan while I was stationed at RFE/RL’s headquarters in Prague, Czechia. Not a day passed without him calling my desk with a news item. Primarily based in Zabul, he consistently approached each story pitch with enthusiasm.

He addressed fundamental tenets vital to any human society, such as the right of girls to receive an education and the imperative for families to recognize that women should have access to healthcare when they are ill. He also stressed that a single drop of vaccine can save children from polio and dispelled the prevailing misconception in his war-torn and illiteracy-stricken hometown of Zabul that vaccines are suspicious Western imposition.

Menapal’s evolution, despite being immersed in a prevailing mentality that resisted women’s education and political participation, mirrored Afghanistan’s broader transformation from conflict to a renewed focus on reconstruction and human rights. It was also a testament to the fact that for Afghanistan to journey from conflict to stability, education was not just important – it was indispensable.

Menapal was the first of his 18 siblings who could go to school in his district. His father, like many other Afghan men, had married twice and couldn’t afford the basics for the crop of kids he had produced over the years. So Menapal went to school barefoot. He carried his books in a cloth bag that UNICEF donated to impoverished families in rural Afghanistan.

The class he attended did not have a building. To him, school was just a bunch of kids sitting in the shade of a tree on the ground. The blackboard was either the tree trunk, a piece of cut wood, or a wall; chalk was a burned branch. When it rained, school was closed.

“I walked an hour on foot to school every day. By the end of each term, my feet would burn, shed their skin, and develop a new layer. The sun scorched them,” he recounted in his speech upon receiving the prestigious David Burk Award for bravery and excellence in journalism. “In the end, my feet simply gave up and stopped hurting,” he added with a grin, displaying his characteristic audacity in self-deprecation.

Despite it all, Menapal eventually earned a degree in political science from Kabul University, the country’s oldest institution of formal higher education. He encouraged young people to pursue education and learning, and claimed to represent Afghans who had chosen the most complex and painful path – education. And he became a reporter.

When the Taliban kidnapped Menapal in 2008, I had little hope for his release. It was widely known that Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty had been a CIA-funded news organization during the Cold War, despite its editorial independence. Following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, Menapal, like other Afghan reporters who worked for Western media, was viewed as a representative of the invaders. I feared he might meet the same fate as Ajmal Naqshbandi, the 24-year-old freelancer whom the Taliban beheaded in 2007 in Helmand province. The Taliban released a video of the beheading that served as a chilling warning to others.

But after spending days in captivity, Menapal was miraculously released through the persistent mediation and negotiation efforts of local communities. After his release, I assumed he would not return to journalism, but I was mistaken. If anything, he became a more forceful critic of the Taliban. Inspired by his newfound freedom, he went from village to village after hearing stories about education, reconstruction, women’s rights, and the importance of the rule of law for the future prosperity of Afghanistan.

He believed it was ultimately up to the Afghan people to develop their country, a sentiment I partially shared. As the Taliban gained prominence over time, I felt that Afghanistan would need to rely on the United States for a long time – perhaps half a century – until it could establish solid institutions capable of producing at least one generation of highly educated men and women to sustain for itself the progress that was made. I believed that Afghanistan was far from being able to sustain itself if the United States withdrew. My pessimism stemmed from many factors: the resurgence of the Taliban, the warlords who held high government positions and abused their power, and the rampant corruption that spread like wildfire.

But Menapal viewed the progress Afghans had made since the fall of the first Taliban regime in 2001 as “good enough” to sustain and strengthen the nation. The country conducted presidential elections in 2004, adopted a new constitution in 2005, and established a parliament that reserved 27 percent of seats reserved for women, alongside thousands of police and military personnel.

Our different perspective on Afghanistan’s progress did not deter our shared commitment to rectify injustices.

I would occasionally make fun of my friend’s name. The literal translation of “Dawa Khan Menapal” roughly means “medicine and guardian of love,” which led me to affectionately refer to him as “love medicine,” suggesting that he could heal Afghanistan with his compassion. He would laugh. Though we were not related, he addressed me as “cousin,” a gesture of respect among the Pashtuns, signifying a pledge of loyalty and protection.

He possessed a vision for the future, and I had anticipated his entry into the political arena long before he was appointed as the spokesperson for the Afghan president. However, I harbored doubts about whether he would have the opportunity to fulfill his full potential.

The first sign of the Afghan government’s eventual downfall was the opening of the Taliban’s political office in Doha in 2013. My apprehensions were validated after the United States announced its exit in 2014.

In 2019, Menapal told me that Afghanistan had come a long way, and the presence of many educated Afghan men and women at the Arg, the ancient presidential palace that had witnessed both the country’s glory days and its darkest moments, bolstered his confidence. However, he was among the Afghans who refused to believe that the U.S.-led coalition was leaving and certainly did not think that the Islamic Republic would collapse before the last American boots were off the ground.

I thought his fight was over when the 2020 Doha agreement was signed between the U.S. government and the Taliban. I felt a deep sense of despair as I observed my journalist colleagues and friends in Afghanistan, knowing that I would be unable to assist them in the face of an uncertain destiny approaching. I chose to resign from RFE/RL, giving myself time to process and reconsider my purpose in life.

Nevertheless, Menapal perceived an opportunity. While most Afghan government officials were seeking ways to escape the country with their families, he asserted that it was time for Afghans like himself to take the lead in defending their homeland against the Taliban. He accepted the position of head of the Afghan government’s Media and Information Center in 2021 – a decision that ultimately cost him his life.

In those uncertain days amid the U.S. withdrawal, we were riveted to Radio Television Afghanistan (RTA), the Afghan state broadcaster. It, like nearly every Afghan news channel, reported Menapal’s assassination. In the images that flickered across our television screen, my friend’s blood had soaked his dark, curly hair. The dark turquoise of his shirt blended seamlessly with the red, making it barely discernible.

Menapal lay in the front seat of the taxi he had taken to the mosque to attend Friday prayers. Many Afghan officials at that time opted for local taxis rather than government vehicles, an attempt to evade assassination attempts. The assassin had shot him in the head and chest.

His body slumped against the door, and his head tilted almost to his shoulder. His hand, adorned with a silver watch and a ring, dangled almost out of the vehicle. When police permitted reporters to access the scene in Kabul’s Dar-ul-Aman neighborhood, the right door of the taxi was riddled with bullets and hung ajar. The front windshield of the car was cracked, but not completely shattered.

The driver’s body didn’t seem as bloodied. His head was on the steering wheel, facing down, as if he had hidden his face to evade the carnage.

As the news spread, I received more and more calls and messages from friends in Kabul, Prague, and the United States; everyone expressing the same sentiment: “Oh my God! They finally killed him.” I had to turn off my phone, yet I couldn’t suppress the urge to learn more. So, I called a mutual friend at the national security advisor’s office.

“They [the Taliban] have slit our throats and silenced our voices,” he said before abruptly hanging up. I understood there was nothing further to discuss.

The news was disseminated quickly, and CNN, TRT World, and others broke the information to the English-speaking world. Later, the then-spokesperson of the White House, Jen Psaki, appeared before journalists to condemn the assassination of the then-Afghan government’s top media official.

Shortly thereafter, the Taliban’s spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, issued a statement declaring the assassination a “victory.” He proclaimed, “In a special operation, the head of the Kabul administration’s media team has been eliminated.” Unlike many high-profile assassinations, in which the Taliban typically refrained from claiming responsibility, they swiftly took credit for Menapal’s killing.

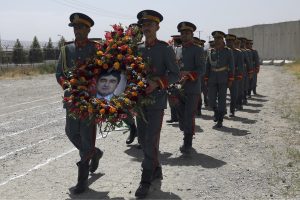

I couldn’t take my eyes off the image of Menapal’s coffin, draped in the black, red, and green Afghan national flag, lying before a bereaved crowd of friends and family.

Then-President Ashraf Ghani, standing solemnly before Menapal’s body, condemned the attack as a cowardly strike against Afghanistan’s intellectual heart. He proclaimed that, though Menapal had fallen, thousands more would rise in his place, their pens mightier. Ghani vowed that the assassins would be hunted down and justice served, ensuring his legacy would not fade.

But just a week later Ghani had to leave the country, and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan collapsed.

From the east coast of the United States, approximately 11,000 kilometers away, my family watched as the government of 20 years in Afghanistan crumbled before our eyes. Districts were falling to the Taliban at lightning speed, one after another. History was once again changing course, and the fact that so many lives were at stake had numbed us all.

On August 18, Mujahid, the Taliban spokesperson addressed the media from Menapal’s former desk at the Afghan government’s Media and Information Center, declaring the end of America’s longest war in Afghanistan.

Three years later, Afghanistan remains subject to global sanctions, leading to its effective isolation from the rest of the world. Millions of Afghan girls are denied the fundamental right to education beyond the sixth grade. This downfall underscores the tragic symmetry of Menapal’s death: his vision for an educated Afghanistan was murdered not long after he was.