Many Singaporeans were surprised and amused last week when Prime Minister Lawrence Wong spoke in his first-ever National Day Rally speech about the years he spent studying in Michigan. He began the story by mentioning the U.S. state’s most famous ghost town. Its name? Singapore.

Wong only talked about the town for a minute to set up a contrast. Singapore, Michigan, lasted barely more than 50 years before being swallowed up by the dunes of Lake Michigan, but Wong hopes that the country of Singapore will be around “for the next thousand years and beyond.”

Most Singaporeans I saw reacting online said similar things: I can’t believe there was a town in America called Singapore! I was surprised and amused for different reasons.

After spending five years researching, living, and working in the original Singapore as an anthropologist and linguist, I’ve spent the last four years studying the ghost town of Singapore, Michigan. I’ve combed through local archives, surveyed the physical landscape, and interviewed dozens of community members about the town.

The remnants of Singapore, Michigan are buried in sand. Today, the former town is owned by a private developer and closed to the public. It’s also caught in ongoing lawsuits, and the plans for its development are deeply contentious, not only locally but also in places hundreds of kilometers away like Chicago and Detroit.

Singapore, Michigan has more – and more challenging – lessons than Wong’s speech let on. The ghost town can give more than a sense of pride about being the Singapore that survived. It offers lessons about environmental management and historical memory that can reshape Singapore’s local and regional commitments today.

Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong waves during his address at the National Day Rally in Singapore, Aug. 18, 2024.

What Was Singapore, Michigan? Why Singapore?

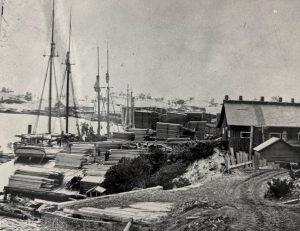

I want to start by setting the record straight. Wong’s description of Singapore, Michigan wasn’t exactly wrong, but intentionally or not, it was misleading. In the speech, he said that the town was founded in the 1830s and “became a busy lumber and shipbuilding town.” Busy, yes – but not large, and certainly not significant. At its peak, Singapore didn’t have more than 500 people living in the town, and for decades never passed 200. Singapore was really more of a factory than a community.

Wong also anticipated a question I have learned everyone asks almost immediately after learning about the former town: why the name Singapore? Wong’s answer was again mostly correct – no one knows why – but he also claimed that “it was very likely inspired by a British port in the exotic Far East founded in 1819,” the Singapore of Southeast Asia. He didn’t quite say that Singapore was a direct source of inspiration for the town’s founders, but his description implies that the influence was more substantial than it was.

The fact is that any “inspiration” was extremely indirect. There’s no evidence that the town’s founders knew anything at all about Southeast Asia or could even pinpoint the location of their town’s namesake. The White settlers of Michigan also weren’t above making up names that they thought sounded exotic, Indigenous, or just plain fun. In other words, there’s no reason to suspect that it was the founders’ knowledge of, or admiration for, the original Singapore that motivated its naming.

Of course, Wong isn’t an anthropologist or historian, and the people who told him about the ghost town of Singapore, Michigan, probably weren’t either. I share these corrections because it’s important to understand the buried town of Singapore, Michigan doesn’t “illustrate the theme of staying resilient and rising above challenges in a troubled world.”

It’s a warning that connects sand to memory. The story of Singapore, Michigan highlights the dangers of pursuing competition over cooperation and encouraging a community to ignore its history.

A cottage partially buried in the sands alongside Lake Michigan and the Kalamazoo River, ca. 1918. This photo circulates as an image of “buried Singapore,” but is more likely a photo of a cottage built during the early 20th century that also suffered the same fate as Singapore due to its proximity to the sands released by Singapore’s lumbering practices. Photo courtesy the Saugatuck-Douglas Historical Society archives.

Singapore Sands

In Michigan, Singapore is sometimes called “Michigan’s Imaginary Pompeii.” The phrase was first quoted in a Detroit, Michigan newspaper in the 1930s and became immortal when it was recycled by the historian Charles R. Starring in 1953. But for all its color, this phrase, too, is misleading. The town wasn’t swallowed up all at once in a catastrophic event, thriving one day but engulfed by sand the next. The burial of Singapore, Michigan also wasn’t an act of nature. It happened because of human environmental mismanagement.

The town of Singapore, Michigan was founded with big ambitions. Its founders dreamed that the town would outcompete Chicago as the economic, social, and cultural powerhouse on the American Great Lakes. In 1871, when misfortune struck Singapore’s rival in the form of the Great Chicago Fire, Singapore’s timber industry boomed. The forests around the town were quickly clear-cut to meet demand. Without the trees to hold the sand in place, the dunes began to shift, and within four years, residents were forced to abandon the town.

The competition between closely connected cities is just one side of the story. The other side is the competition between White settlers and the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Tribes who have stewarded the land for millennia. Singapore, Michigan taught settlers a hard lesson about managing the fragile forest and dune ecosystems, but their self-styled Native American competitors had possessed this knowledge long before.

The view from the tallest dune just outside the present-day town of Saugatuck, Michigan, towering roughly 85 meters (280 feet) above Lake Michigan. The dunes that bury Singapore, Michigan are faintly visible in the distance near the lakeshore. Photo by Joshua Babcock 2024.

The parallel between Singapore, Michigan’s relationship with sand resonates with the fraught role of sand in Singapore, the country. Wong’s first National Day Rally speech was mostly standard fare: plans for businesses, workers, families, students and the future of Singapore’s economy and built environment. But like the cause of the sands that swallowed Singapore, Michigan, Singapore’s coastline is anything but natural.

Singapore is the world’s largest sand importer, and while Singapore only imports sand with proper documentation, there’s evidence that players further up the supply chain are sidestepping local and international regulations. Unsustainable dredging practices driven by Singapore’s demand create adverse effects, from fishery collapse to drought throughout Singapore’s neighboring ASEAN countries where the sand is dredged, especially Cambodia.

This might not seem like it’s Singapore’s problem. But especially when it comes to environmental issues, no country can act like an island – not even a country that is literally an island, like Singapore. Singapore, Michigan shows that solving local problems by prioritizing pure competition over cooperation hurts everyone in the long run.

Memory Is Political

The State of Michigan’s historical marker for Singapore, MI, located outside the Saugatuck Village Hall. Installed in 1958, the marker is down the Kalamazoo River roughly 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) from the site of the former town. Photo by Joshua Babcock 2023.

Wong concluded his story about Singapore, Michigan by showing a photo of the town’s historical marker, which was placed in the nearby town of Saugatuck in 1958. He said: “Today, only a signboard remains as a marker of its existence.”

This statement is more obviously incorrect. A 2017 archaeological survey of the site by a team of archaeologists at Michigan’s Ball State University found around 200 artifacts in the sand. When Singapore was finally abandoned in the 1870s, around 11 houses were relocated, either piece-by-piece or rolled on logs, fully intact, down the frozen Kalamazoo River to the towns of Saugatuck and Douglas. You can visit approximately five of the “Singapore Houses” in these towns today. The building that once housed the infamous Wildcat Bank of Singapore – which in the late 1830s issued currency, the Singapore Dollar, until the state’s laws changed and the Singapore Dollar was found to be backed by fraud, not gold – now houses an art gallery in downtown Saugatuck.

Beyond these physical remnants, the town’s existence is extensively documented in publications and the archives maintained by volunteers from the towns of Saugatuck and Douglas. Local historians have spent their entire lives researching and writing books about Singapore, Michigan, and the Saugatuck-Douglas Historical Society regularly gives free talks to further educate the public about the ghost town.

Artifacts unearthed during the 2017 Ball State University excavation of the Singapore Archaeological Site. The survey found more than 200 objects, including glass bottles, metal parts, and textiles. Artifacts courtesy of the Saugatuck Douglas Historical Society. Photo by Joshua Babcock 2024.

This is Singapore, Michigan’s far more challenging lesson for Singapore. As the recent controversy over the new statues at Fort Canning Park shows, in Singapore today, the question of what to remember and how to remember it remains complex and contentious.

The town of Singapore, Michigan is facing a standoff today between private developers and locals. The developers, like Wong, insist that nothing remains: that there is nothing worth remembering or preserving on the archaeological site of Singapore, Michigan, either environmental or historical. They have argued for nearly two decades that the land is better used today for things like condos, private marinas, and a country club.

Yet the residents of the towns who refuse to forget the past aren’t convinced. They know the stories and remember the past, and this isn’t a barrier to progress. Their historical memory just might offer a better path forward – one that doesn’t continue to accelerate environmental harms like those created by their competition-minded ancestors who caused their dreams’ premature end.

A fragment of a wooden plank from a house in the former town of Singapore, Michigan. The plank is pasted over with a newspaper from New York, either for decoration, insulation, or both. Artifact courtesy of the Saugatuck Douglas Historical Society. Photo by Joshua Babcock 2024.