Early last month, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio met with German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin. Both leaders had attended the NATO Summit in Washington, D.C., so they could have met there, but the fact that he traveled halfway around the world to Germany for this meeting shows just how much the Kishida administration values the bilateral relationship. With the Germany-Japan Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement coming into force and the establishment of a consultative framework on economic security, the cooperative relationship between the two countries appears to be deepening steadily.

Take, for instance, the participation of the German Air Force in training with the Japanese Air Self Defense Force in Hokkaido, which also took place in July. Meanwhile, the German Navy will be docking in Tokyo Bay this week, to be followed by its Italian counterpart a few days later.

Viewed in a broader context, however, it becomes hard to argue that the two leaders are truly fulfilling their roles adequately in light of the heavy responsibilities placed on their respective countries. The Washington NATO Summit was commemorating the 75th anniversary of the founding of the alliance, and it was the third gathering since the leaders of the IP4 (Indo-Pacific 4: Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand) began participating. The main preoccupation of the attendees, however, was preparing for the “post-Biden” era. With the United States, long the West’s dominant power, looking increasingly unsteady, Japan and Germany find themselves with more responsibility than ever in supporting the free world.

Yet both Kishida and Scholz are struggling with low domestic approval ratings, and both have faced criticism for a lack of leadership. In fact, Kishida announced that he will be stepping down after the ruling Liberal Democratic Party elects its new leader in late September. At the same time, the chances of Scholz leading his party into the next Bundestag election in 2025 also look increasingly small.

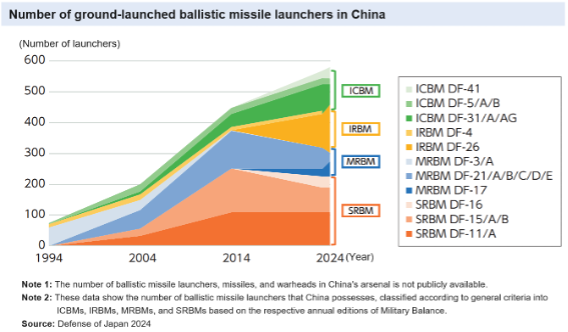

Still, Japan has at least redefined its national priorities. By the time the government settled on the three national security documents at the end of 2022, a panel of experts had been formed to engage in discussions, clarifying which capabilities Japan needed to strengthen, and come up with detailed plans for the next five and ten years. In East Asia, the missile capabilities of China, which has never been bound by the INF Treaty, have become a serious threat after years of steady buildup.

As the war in Ukraine unfolded, so did the debate in Japan on its national security policy, leading to the inclusion of the importance of so-called “counter-strike capabilities” as an element of deterrence. In addition to expanding the range of domestically produced missiles, a decision has been made to purchase about 400 Tomahawks from the United States, with the first 200 to be supplied by the end of 2025. Kishida has as yet given no indication as to where the funds for these acquisitions will come from. But at least Japan has built a consensus on what needs to be done, in stark contrast to Germany, where the defense minister regularly complains that the government cannot buy what it needs because the purse strings are too tight.

Meanwhile, although the National Security Strategy was announced in Germany in 2023, the country seems a long way from any kind of national consensus on what capabilities it needs to bolster. Alongside the NATO Summit, an announcement was made of the deployment of American long-range missiles in Germany. The U.S. and Germany agreed to deploy Tomahawks, SM-6s, and supersonic missiles – these last under development – in Germany from 2026. These are capabilities that correspond to the “counter-strike capabilities” that Japan decided to introduce in its National Security Strategy 2022, and as such may be seen as an important move to help rebuild Western deterrence. However, no press conferences were held by the leaders or cabinet members of either the United States or Germany; the facts simply emerged suddenly from the White House.

In response to this White House announcement, many German media outlets ran headlines along the lines of “Is the Cold War Making a Comeback?” For the Germans, medium-range missiles immediately conjure up memories of NATO’s Dual-Track Decision in 1979, followed by the deployment of the “Pershing II” intermediate-range ballistic missile and the Griffon ground-based cruise missile in Germany, which triggered large-scale anti-nuclear protests. Fortunately for all, Mikhail Gorbachev later took power, and Washington and Moscow signed the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, leading to the removal of all ground-based missile launchers between the ranges of 500 and 5500 km. The treaty defused what was at the time a major crisis for the NATO alliance.

The intermediate-range missiles deployed in the 1980s were equipped with nuclear warheads, while the missiles to be deployed this time have conventional warheads. In that sense, the analogy does not hold, yet the reaction in Germany was nonetheless emotional, and many politicians have expressed fears that this might be the beginning of an arms race. Responding to these concerns, Defense Minister Boris Pistorius appeared on TV and explained that NATO clearly has “holes” in its capabilities at present and that it cannot even start a rapprochement unless it fills them and restores deterrence.

Around the same time, Germany, France, Italy, and Poland announced that they had agreed to develop long-range missiles. And so the structure of deterrence in both Europe and East Asia is gradually taking shape. It gives nuclear weapons a smaller role than they had during the Cold War, while assigning a bigger role to the long-range precision strike power of conventional warheads. The term “integrated deterrence” is increasingly used to describe this new approach. But to what extent nuclear deterrence should play a role and what kind of nuclear component is required to fulfill this role has yet to begin. In Europe, the nuclear sharing system with dual-capable aircraft is understood to act as a link to the strategic deterrence of the U.S. military. Do Asia need something similar, or should the region use a different means of ensuring the credibility of extended deterrence? This debate, too, has only just gotten underway. The world needs Japan and Germany to be on top of security policy, and willing to lead.