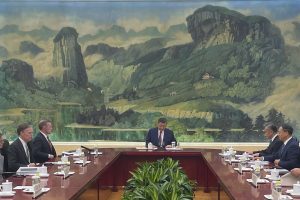

U.S. President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, recently made a high-profile visit to China, which he described as aimed at the “responsible management” of China-U.S. relations. Sullivan’s meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping was the first by a U.S. national security adviser in eight years, highlighting its diplomatic significance. While it is tempting to label the visit a success, especially given its timing during the height of the U.S. presidential election race, its practical purpose went beyond managing tensions. It also served as a warning to China not to interfere with the U.S. election.

However, a pressing question remains: Why did China treat Sullivan with surprising cordiality, especially given that Biden himself will soon step down, granting Sullivan a face-to-face meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping?

Just before the national security adviser’s visit, the United States imposed a massive new tranche of sanctions on 42 Chinese firms for supporting Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine. Yet, this didn’t deter Xi from meeting Sullivan.

Some interpret it as a “goodwill gesture” toward the outgoing Biden administration. However, Beijing’s sudden softer tone, evidenced by Xi’s amicable photo-op with Sullivan, warrants deeper analysis. Xi is well-versed in the art of photo-op diplomacy, using such moments to convey his emotions. For example, during his meeting with the late Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in 2014, Xi adopted a famously solemn expression, avoiding eye contact. When Abe attempted to speak, Xi pointedly turned away, facing the cameras instead.

According to official Chinese Foreign Ministry reports about the visit, Sullivan appeared to have offered a list of assurances that aligned with China’s interests. Sullivan told Xi that “the United States does not seek a new Cold War, does not aim to change China’s system, and does not support Taiwan independence.”

In his meeting with Wang Yi, China’s top diplomat, Sullivan provided a more comprehensive reiteration on Taiwan that raised eyebrows. He stated that the United States does not support “Taiwan independence,” “two Chinas,” or “one China, one Taiwan.” This is known as the “Three Nos” policy regarding Taiwan.

While elements of this policy had been expressed separately or partially by various U.S. administrations, the last time all three elements were explicitly stated together in an official setting in China was, over 20 years ago, by President Bill Clinton in 1998. In response to Clinton’s “Three Nos,” concerned lawmakers in both the Senate and the House nearly unanimously passed resolutions reaffirming the U.S. commitment to Taiwan.

After Clinton’s statement, subsequent administrations generally refrained from repeating the full “Three Nos” formulation, often focusing mainly on the non-support for Taiwan independence, until Sullivan did so on this occasion.

Moreover, Sullivan requested and was granted a meeting with General Zhang Youxia, marking the first time a U.S. national security adviser has met with a vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission (CMC) since 2016. Sullivan described this opportunity as “rare.” Zhang, the second-highest military decision-maker in China, used the occasion to emphasize that Taiwan is “the core of China’s core interests” and the “first unbreachable red line in China-U.S. relations.”

Based on these official statements, it is evident that China successfully secured key reiterations from the United States. that align with its interests, while also clearly articulating its own demands.

Notably, the Chinese account of the meeting was more detailed and explicit than the U.S. version. For example, in the English readout Wang outlined five key points in over 950 words, emphasizing that China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, political system, development path, and the legitimate rights of its people must be respected. Wang further urged the United States to adopt a “correct perception” of China and to cease its economic, trade, and technological suppression.

In the broader context, the meeting appears to be a follow-up to the Biden-Xi summit held in San Francisco last November, during which both leaders committed to reducing tensions, albeit for different reasons. Washington aims to focus on the upcoming presidential election without disruption from China, while China seeks to buy time in the Sino-U.S. competition in order to revitalize its struggling economy.

Xi’s emphasis on seeking “peaceful coexistence” and maintaining “stability in China-U.S. relations” reflects a desire for a stable external environment to address these internal issues. This approach aligns with China’s current focus on economic recovery and its need to navigate domestic challenges without external pressures exacerbating the situation.

From the U.S. perspective, the goal is to prevent China from provoking geopolitical tensions in sensitive regions such as the South China Sea, Taiwan, and the Philippines. The United States also seeks to dissuade China from supporting Russia’s war against Ukraine or forming a trilateral alliance with North Korea and Russia. In contrast, China is keen to avoid further economic and technological pressure as it focuses on economic recovery in a stable external environment.

The fact that Xi agreed to meet with Sullivan supports the interpretation that Sullivan’s talks with senior officials, including Wang and Zhang, were productive. China often leaves the possibility of a meeting with Xi uncertain until the last moment, keeping visiting delegations in suspense. Xi’s decision to meet with Sullivan suggests that he was pleased with the progress made during their discussions.

China’s broader strategy seems to be the creation of a relational blueprint that secures its interests, particularly as the U.S. political landscape shifts. By positioning itself now, Beijing can potentially influence the next U.S. administration, using these agreements as a foundation for future China-U.S. relations that align with its long-term goals.

This reaffirmation of bilateral principles favorable to China could serve as leverage for Beijing in dealing with the next U.S. administration, particularly if Vice President Kamala Harris, who has limited foreign policy experience, succeeds Biden. Given Harris’ likely adherence to Biden’s foreign policy approach, Beijing may strategically use Sullivan’s visit to ensure that, if she assumes office, the agreements forged between Biden and Xi are maintained.

With less than six months remaining in Biden’s term, both nations are preparing for the transition. Washington appears focused on maintaining stability during the election season, while Beijing is balancing its immediate need for economic stability with its long-term strategic ambitions. The disparity between China’s comprehensive readouts and the relatively brief summaries from the United States underscores the differences in their respective approaches.

Ultimately, China’s long-term strategy is clear: It is looking beyond the current administration to shape U.S. perceptions of China, convincing Washington that its rise does not pose a threat and creating a more favorable environment for advancing its ambitions.