Japan is facing a rice shortage. Online sellers and grocery stores are struggling to meet the demand for this crucial staple. Historically, rice shortages have led to political instability and even riots, as seen in 1918 and more recently in 1993.

The current crisis gained national attention following the August panic buying of rice after the Japan Meteorological Association warned of a potential mega-earthquake and the need to stockpile essentials. Social media posts of empty shelves added to the urgency as people rushed to buy rice before stores ran out.

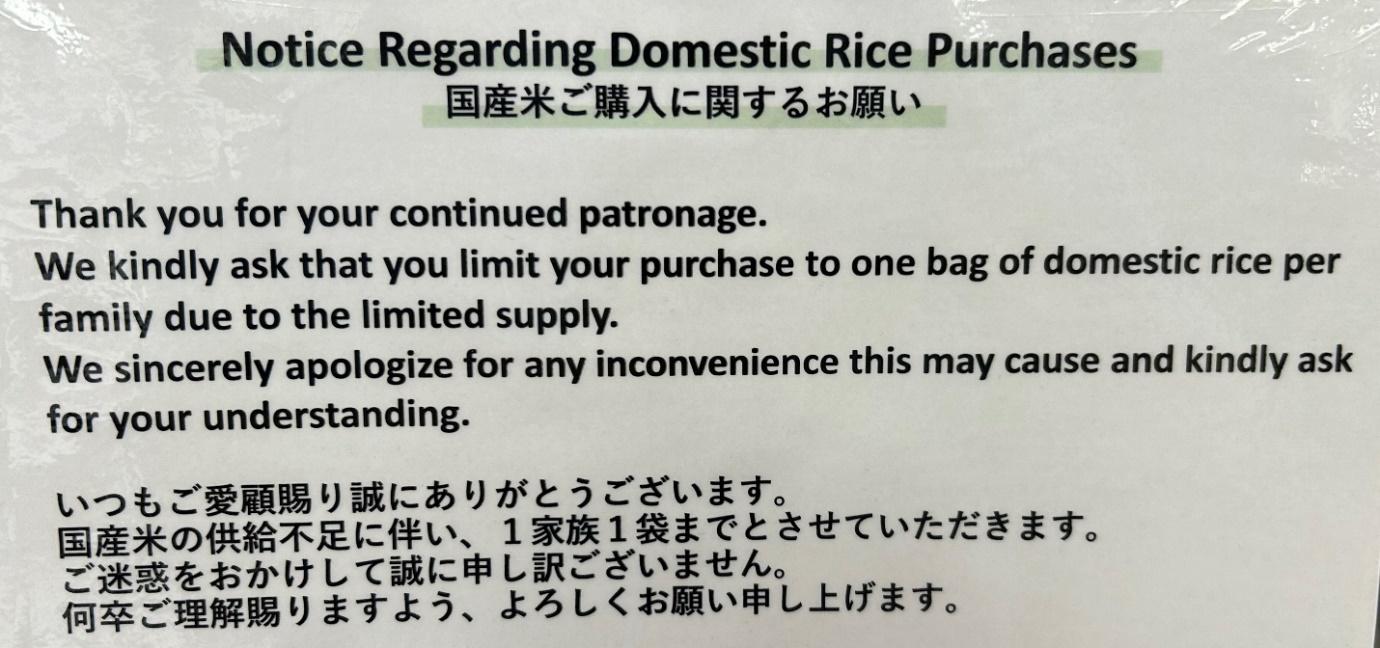

But the shortage continued beyond the panic buying, with restrictions on rice purchases stretching into September.

A sign posted at a Tokyo grocery store on Sept. 10, 2024. Photo by Andrew Orchard.

At first glance, the shortage should not have occurred. Japan’s 2023 rice harvest looked fine statistically. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) gave the crop situation index for 2023 rice production a harvest rating of 101 (101 to 99 is considered an average harvest).

Despite quantity meeting the mark, quality did not. Extreme heat led to only 59.6 percent of 2023’s harvested rice being given the highest quality grade, a 16-point drop from 2022. This decrease drove the price of rice to an 11-year high in July 2024. Such high prices and fears of further increases also contributed to the panic buying.

Some Japanese media cited the post-COVID-19 influx of foreign tourists as a significant contributor to the shortage and sharp price increase. Experts have pushed back on this assumption, however. Former MAFF official Yamashita Kazuhito assessed foreign tourists as a “minor factor” in the ongoing shortage. Foreign tourists account for around 0.5 percent of total annual rice consumption in Japan at the most.

According to experts like Yamashita, the government’s tight control over rice production is a significant factor behind the current shortage. Dated policies focused on maintaining rice prices and farm subsidies have made the supply inelastic. This means that events like panic buying and the influx of tourists can significantly stress the Japanese rice supply. These experts believe the current shortage highlights the urgent need for policy reform and change in the rice production sector.

Even if Japan wishes to increase rice production, its current capacity may prevent it. Japan’s rice acreage reduction policy has decreased the farmland used to grow rice by 20 percent over the past decade. Repurposing farmland back to rice production will likely take several years and be difficult for the aging rice farmer population; 90 percent of rice farmers are over 60 years of age.

Given climate change’s effects, planting more heat-tolerant rice varieties is also likely needed. Heat-tolerant grains accounted for just over 14 percent of all rice grown in Japan during 2023. Continued promotion of such grains, concurrent with implementing prescribed heat mitigation measures, is required to yield a good harvest.

Meanwhile, the 2024 rice harvest is making its way to stores across Japan. The government is hopeful that this new rice, along with the continuation of rice purchase restrictions, will bring an end to the shortage by late September. However, it’s important to remember that these measures, while significant, won’t solve the underlying issue. This requires policy changes that can enhance the resilience of Japan’s rice supply over the long term.