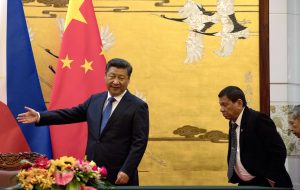

Shortly after coming to office in mid-2016, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte traveled to Beijing on a state visit. There, in the Great Hall of the People, he announced his “separation” from the United States. The announcement shocked both the Philippine public and a political and military establishment that had long been wedded to its American security ally. Subsequent years would see a weakening of the relationship between Manila and Washington, as Duterte downplayed maritime disputes in the South China Sea and courted President Xi Jinping’s support for large-scale infrastructure projects.

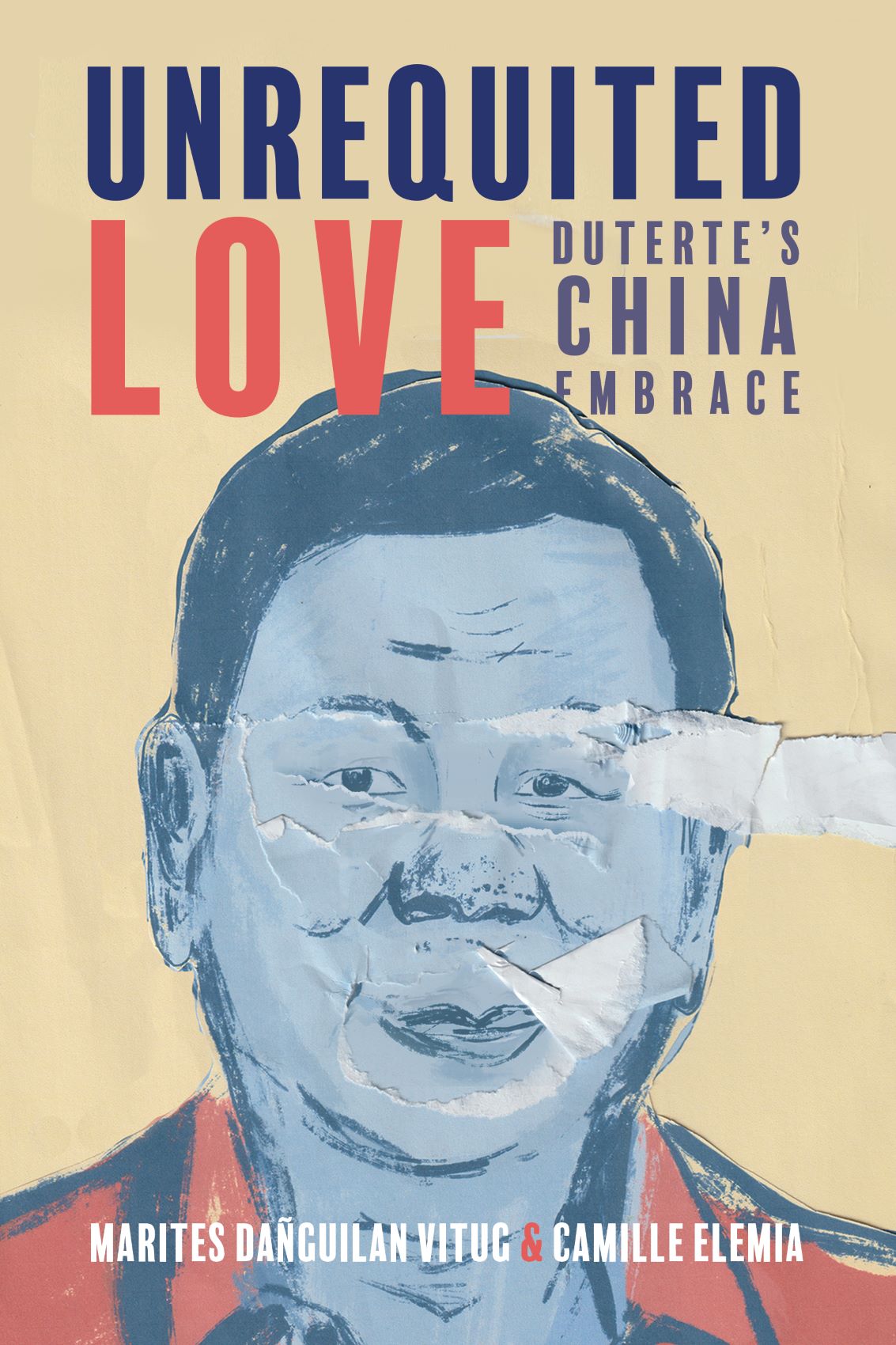

What motivated Duterte’s turn to China, and what impact did it have? A recently published book, “Unrequited Love: Duterte’s China Embrace” (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2024), co-authored by journalists Marites Vitug and Camille Elemia, examines the course of the Philippines’ foreign policy under Duterte and what motivated the erratic leader’s pivot to China.

Sebastian Strangio, the Diplomat’s Southeast Asia Editor, spoke to Vitug, a veteran Filipino journalist and editor, about how Duterte’s foreign policy differed from previous pro-China administrations, and whether she thinks another lurching reorientation is in the Philippines’ future.

First off, tell us how Duterte changed the Philippines’ foreign policy after taking office in mid-2016. What did he seek to achieve by moving closer to China, and how did this change (if at all) during his time in office?

Rodrigo Duterte was the first Philippine president in contemporary history to openly and unabashedly embrace China. In his first visit to China as president in October 2016, he announced during a Philippine-China Trade and Investment Forum at the Great Hall of the People his “separation from the United States…so I will be dependent on you for all times.” It was a dramatic foreign policy shift that stunned many, including some members of his Cabinet. He said he needed China’s help – investment, loans, and aid – to boost the Philippine economy. It was a pragmatic move, also driven by the fact that he hated China’s rival superpower, the U.S., for criticizing his war on drugs, among other reasons. (I will delve into this later).

A few hours after Duterte declared his “separation” from the U.S., his finance and economic planning secretaries, who were with him in Beijing, did some damage control. They issued a statement clarifying that the Philippines was not turning its back on the West. Rather, the Philippines “desires stronger integration with our neighbors” as Asian economic integration was “long overdue.”

Duterte changed the country’s foreign policy unilaterally, true to his autocratic character. He did not consult with key members of his Cabinet, those that implemented foreign policy as well as economic policy, namely the foreign affairs and defense secretaries, and the economic team lead by the finance secretary. While the President is the architect of foreign policy, he needs to work with government institutions to make this policy work. Thus, it was difficult for Duterte to change the strategic thinking of the defense and security establishment and the foreign affairs department – and sway it towards China – because this has been moored in more than 70 years of a security alliance with the U.S.

The title of your book – “Unrequited Love” – hints at Duterte’s affection for China and you include a number of quotes from Duterte in which he explicitly describes his “love” for China or Xi Jinping, or both. What do you think Duterte saw in China? In what ways was this affection “unrequited”?

Duterte regarded China as a friend – a rich and powerful one – someone who could continue to grow the Philippine economy. Equally important was the fact that China did not pass judgment on his bloody war on drugs which was Duterte’s centerpiece program. On a personal level, he was comfortable with President Xi Jinping, traveling to Beijing to meet Xi five times during his six-year term. Duterte was not shy in declaring his love for China and Xi.

A few weeks into his presidency, the Philippines won a maritime case it filed against China with an international arbitration court, which declared China’s nine-dash-line claim illegal. It was regarded as a historic victory but Duterte chose to ignore it, calling it a piece of paper fit for the rubbish bin. He did not use it as leverage to negotiate with China.

Despite Duterte’s appeasement of Beijing, China continued its aggressive behavior in the West Philippine Sea (part of the South China Sea that falls within the Philippines’ EEZ). The China Coast Guard (CCG) blocked and water-cannoned resupply missions of Philippine vessels to troops aboard BRP Sierra Madre, a World War II ship beached on Second Thomas Shoal. During one extended period, at least 200 Chinese ships, including those of their maritime militia, swarmed Julian Felipe Reef (Whitsun Reef), intimidating the Philippine Coast Guard and fishermen. Similarly, in a provocative move, Chinese fishing ships, accompanied by People’s Liberation Army Navy frigates and CCG vessels, surrounded Sandy Cay, a sandbar of Pag-asa (Thitu) Island, which is occupied by the Philippines.

The 2016 international arbitration court also ruled that Filipinos, Vietnamese, and Chinese can fish in Scarborough Shoal, which China controls because it is a common fishing ground. China rejected the court’s ruling. Sometimes, they allowed Filipino fishermen to ply their trade in Scarborough Shoal but this was dependent on terms set by the CCG.

Looking back, China did not return Duterte’s love.

What underpinned this shift toward China? To what extent did it flow from a coherent view of foreign policy on the part of Duterte and his team, and to what extent did personal factors play a role?

Duterte’s pivot to China was driven by a number of factors: the milieu in which he grew up in Davao wherein he developed close friendships with migrants from mainland China as well as Chinese-Filipino businessmen, and his disdain of the U.S. because of personal and official reasons. He claims to have been mistreated by a supposedly arrogant U.S. immigration officer at the Los Angeles airport, this when he was a member of Congress. When he was mayor, an American treasure hunter who accidentally blew himself up with explosives in his hotel room was reportedly spirited out of Davao by FBI agents. This angered Duterte who wanted to question him, calling the incident an affront to Philippine sovereignty. These experiences stayed with him until his presidency.

Duterte also claimed to have socialist leanings, saying he was influenced by the late founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines, Jose Ma. Sison, who was his teacher in college.

He was not a strategic thinker. His foreign policy flowed from his personal likes and dislikes. It was not only the U.S. that he hated; he was angry at the EU which criticized his war on drugs. Overall, Duterte did not try to balance relations between China and the U.S. He lumped the EU with the U.S., the countries that topped his hate list.

Duterte was not the first Philippine president to want, and seek, close relations with Beijing. How did Duterte’s approach, and the context in which it took place, differ from past Philippine administrations?

Among past Philippine presidents, it was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo who sought close economic relations with Beijing. But she also kept the Philippines’ close ties to the U.S., joining the U.S.-led coalition of the willing in the war against Iraq in 2003. Thus, her approach was different from that of Duterte’s as Arroyo tried to navigate relations with China and the U.S., keeping them both as friends.

For her, China was a source of loans and investments. Under her administration, the Philippines borrowed a multi-million-dollar loan from China for a railway project that was later canceled as it was reportedly riddled with corruption. Arroyo also actively invited China to invest. A state-owned enterprise had agreed to set up a telecommunications network that would link government offices all over the country but got mired in a scandal because of corruption allegations.

She also entered into a deal with China to survey for oil and gas in Reed Bank, which is within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Vietnam vehemently protested and demanded to be included, and thus it became a trilateral arrangement.

During Arroyo’s presidency, there was little friction with China in the West Philippine Sea and this had mostly to do with illegal fishing. The context was different under Duterte: By the time he became president, maritime tension between Manila and Beijing had built up. His predecessor, President Benigno Aquino III, hauled China to an international court after China took control of Scarborough Shoal and after it harassed Philippine ships from surveying for oil and gas in Recto Bank (Reed Bank).

During Arroyo’s presidency, there was little friction with China in the West Philippine Sea and this had mostly to do with illegal fishing. The context was different under Duterte: By the time he became president, maritime tension between Manila and Beijing had built up. His predecessor, President Benigno Aquino III, hauled China to an international court after China took control of Scarborough Shoal and after it harassed Philippine ships from surveying for oil and gas in Recto Bank (Reed Bank).

How would you assess the success of Duterte’s approach, on its own terms? How much benefit – in terms of Chinese infrastructure funding, etc – resulted from his approach?

What’s interesting is how government institutions such as the defense department, the armed forces, the coast guard and the foreign affairs department responded. Two of Duterte’s Cabinet members, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana and Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. did not necessarily toe the pro-China line. They spoke up against China. They were able to do this because Duterte wasn’t really concerned with foreign policy as he was focused on his drug war and anti-crime campaign. What mattered to him was his personal friendship with Xi Jinping. Moreover, Duterte was a hands-off leader who left policy and operational details to his Cabinet secretaries.

Lorenzana, a former Army general, was aware of the sentiment of the men and women in uniform. He had to publicly address their resistance to the pro-China stance of Duterte and his directive for the Armed Forces of the Philippines, especially the Navy, to cooperate and form close ties with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)-Navy. Navy officers we interviewed said that their resolve to enforce the law in the West Philippine Sea and assert the country’s sovereign rights did not change. A commander of a warship said they distrusted China because what they said was different from their actions on the ground. Another officer said it would take more than one term of a president to shift relations away from the U.S.

For his part, Locsin was tasked with negotiating a deal for Manila and Beijing to jointly explore for oil and gas in the resource-rich Reed Bank. Locsin did not give in to China which refused to abide by Philippine laws. The negotiations fell through.

In the end, Duterte failed to rally the country toward China. The pushback, combined with the unpopularity of his pro-Beijing position, thwarted his epic attempt.

On the loans from China: After the state visit, Duterte’s Cabinet men triumphantly announced China’s pledge of $24 billion in investments and soft loans for a long list of major infrastructure projects. Six years later, by the time Duterte stepped down, only three of these projects came to fruition: a dam, an irrigation project, and a bridge. Duterte’s promise to build a mega-railway project in Mindanao and two other areas did not come true.

What do you think was the ultimate effect and legacy of Duterte’s “China pivot”? Do you believe there is a pro-China current in Philippine politics that might see the country take a similar turn in future?

I will focus on the impact of Duterte’s China pivot on the national conversation, the rule of law, and politics.

First: Duterte emboldened pro-China voices to cohere. During his presidency, a small group of pro-China academics and media commentators surfaced; they were active on Facebook. They echoed Chinese propaganda and promoted pro-Duterte content. When Ferdinand Marcos Jr. became president and abandoned his predecessor’s China pivot, this group became critical of Marcos. Still, Duterte, joined by a few politicians like Senator Imee Marcos (sister of the President), continues to amplify China’s propaganda and disinformation narratives.

The targets of disinformation are Marcos and government officials who are outspoken against China. The war narrative has been the most pervasive: that standing up to China would lead the Philippines to war. This is a false choice.

Second: China reinforced Duterte’s disregard for the rule of law. During Duterte’s presidency, the government took shortcuts to speed up the building of infrastructure projects funded by China. For example, the law provides that Indigenous Peoples who would be affected or displaced by an infrastructure project had to be consulted first. In the cases of a dam and an irrigation project, the project plan and bidding of the project came first before the Indigenous Peoples were consulted.

During the pandemic, Duterte and his men flouted rules. Duterte’s guards and some Cabinet members were the first to be vaccinated, thanks to China’s vaccine. This caused an uproar since they came ahead of the health frontliners, who were supposed to be the priority. Duterte himself was vaccinated with Sinopharm, a Chinese vaccine which, at the time, was not approved for use by the health department. When it came to suppliers of personal protective equipment and masks, Chinese firms were favored at the expense of Philippine companies which offered lower prices.

Third: China’s influence is expected to extend to politics. Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of the former president, has not publicly criticized China’s incursions in the West Philippine Sea. She has kept quiet on this issue, refusing to comment whenever she is asked about China’s provocative acts in the West Philippine Sea. Polls show her to be among the most popular national politicians. She is likely to run for president in 2028 and, like her father, she may shift relations back to Beijing.