Seasons change. Summer gives way to torrential rain. Springtime succeeds winter. For Afghan girls and women, however, neither the harsh summer nor the bone-chilling winter brings about a season of change. Before one regressive measure announced by the country’s defiant rulers is processed and a range of self-regulatory steps are initiated by girls and women, the Taliban come up with yet another harsher edict. They simply wait for the international indignation to subside before unleashing another set of restrictions. The onslaught appears to be relentless.

The most recent edict makes it illegal for a woman’s voice to be heard by male strangers in public. With the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice Ministry (a.k.a. the morality police) under strict instructions to implement the edict, this effectively translates to men becoming the sole speakers and women the obligated listeners in public places. This is in perfect sync with the male-only Taliban ruling class’ vision for the country – for men, by men, and of men. It banishes the handful of brave women who took part in protests from the streets of Kabul and a few other cities to the four walls of their homes.

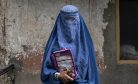

After the latest decree, unemployed women are mostly confined to their homes. When they go outside, they must wear a burqa and be accompanied by a male guardian. They are only allowed to do household chores or work on handicrafts such as carpet weaving, pottery making, or garment stitching.

The situation is just as challenging for employed women working in public health, security, arts, and crafts, as their pay is extremely low, making it difficult to support their families. This has a significant impact on households led by women, especially those who have lost male family members during the four decades of conflict.

The Taliban have also issued strict guidelines for men regarding their clothing and beard length.

The Taliban spokesperson has defended each of the verdicts as either an internal issue or as sanctioned by Sharia, or Islamic law. A few other countries are also ruled by Sharia; none of them bars women from receiving education, working, and speaking. That demonstrates both the intransigence of the Taliban’s supreme ruler, Haibatullah Akhundzada, and his coterie of advisers and his raw power. Only occasionally have a few Taliban leaders of consequence publicly spoken against such decisions, only to find themselves stripped of power. The sizable rest have chosen unity and compliance over airing disappointments.

Meanwhile, the promise that the “Taliban will resolve the education issue” for women is still in the making, for the last two and half years.

On August 15, 2024, the Taliban completed three years in the seat of power in Kabul. Their performance has been largely disappointing. While they have some achievements to highlight – such as reducing poppy cultivation, curbing corruption, limiting the growth of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), increasing tax collection, and preventing a complete collapse of the national economy – each of these accomplishments is fragile. They have managed to build friendly relationships with several regional countries, with the possibility of expanding this list in the future.

Despite criticisms from women’s groups, activists, and some countries, the debate over the Taliban’s continued oppression of Afghan women persists. As the United Nations has officially termed this war on women and girls a “gender apartheid,” a few may believe that these edicts are being used by the Taliban as a pressure point to elicit recognition from the international community. However, there isn’t simply any evidence to this effect. It seems unlikely that the Islamic Emirate is signaling a “recognize us and we may accommodate your concerns” message to anyone.

On the contrary, the Taliban are being upfront about how they view women and their plans for limiting women’s role in every segment of Afghan society. The Taliban’s Vice and Virtue Ministry has said it would no longer cooperate with the U.N. mission in Afghanistan because of its criticism of the latest edict.

Occasional stories of brave and desperate women running underground beauty salons and secret schools have appeared in the international media. These are acts of defiance and can end with a tip-off to the morality police. In January 2024, the Taliban stated that 800 women are in different prisons. An independent investigation in March this year found that about 340 of them are incarcerated in women-only prisons in five provinces of Herat, Ghor, Badghis, Farah, and Nimroz for crimes ranging from making phone calls to men to defending women’s rights. The extreme brutality, including rape, some of these women have suffered inside prisons at the hands of the male guards has also been corroborated by separate reports.

Over the past three years, the Taliban have dashed all hopes of reform and have instead reverted to their regressive policies of the 1990s. Countries that have engaged with them or plan to do so must acknowledge and take responsibility for their role in throwing women’s rights under the bus for strategic gains. The United Nations, which recently met with the Taliban in Doha and made a similar choice, shares in this responsibility. The silence of the international community is deafening. It’s time to take steps to help Afghan women out of the present morass.