On Friday, Vietnam and the Philippines agreed to deepen defense and military relations and collaborate on maritime security, not long before Chinese and Philippine vessels once again collided near a disputed shoal in the South China Sea.

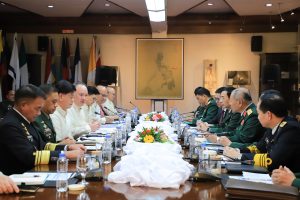

Following a meeting between Vietnamese Defense Minister Gen. Phan Van Giang and his Philippine counterpart Gilberto Teodoro in Manila, the two sides announced that they were aiming to sign a memorandum of understanding on defense cooperation before the end of 2024, Reuters reported.

“The ministers expressed their unwavering commitment to deepen defense and military cooperation through continued interaction and engagements at all levels,” the Philippine Department of Defense said in a statement.

It added that Giang and Gilberto also signed “letters of intent” aimed at enhancing engagements in disaster response and military medicine. They also agreed to “resolve all disputes by peaceful means, in accordance with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

Giang also paid a courtesy call on President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., during which the two sides discussed “the strengthening of the bilateral relations between the Philippines and Viet Nam,” the Defense Department said. Giang’s visit to Manila, his first since his appointment as defense minister in 2021, was intended “to materialize the common understandings” during Marcos’s state visit to Hanoi in January, according to a Vietnamese state media report cited by Radio Free Asia.

During a joint press briefing, Nikkei Asia reported that Gilberto said that the two sides “undertake to sign a memorandum on defense cooperation within this year,” hopefully in time for the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the founding of the Vietnamese armed forces on December 22.

Such an agreement could see Vietnam and the Philippines strengthen their joint maritime cooperation in the face of China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, where both nations have overlapping claims. During a joint press briefing, Teodoro said that the two nations faced “common threats” – a seeming reference to China – and that they would “work together in facing these threats in the spirit of ASEAN solidarity.”

The nature of this threat has become ever more apparent over the past two years, as the China Coast Guard (CCG) has intensified its pattern of incursions into the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone. Until recently, Beijing’s pressure campaign focused on Second Thomas Shoal, and was aimed at preventing the PCG and Philippine Navy from resupplying the unit of marines stationed aboard a grounded warship on the shoal.

The situation has calmed at Second Thomas Shoal since an incident on June 17, in which a Filipino sailor lost a thumb during a melee with CCG personnel. The two sides subsequently agreed on a “provisional arrangement” that allowed for the peaceful resupply of the Philippine garrison at Second Thomas Shoal. But the locus of Chinese pressure has simply shifted to Sabina Shoal, which lies around 60 kilometers to the east, and some 140 kilometers off the coast of the Philippines’ westernmost island, Palawan.

Indeed, the day after Giang and Gilberto put pen to paper in Manila, China and the Philippines again exchanged accusations after a collision between CCG and Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) vessels in the vicinity of Sabina Shoal.

PCG spokesperson Jay Tarriela on Saturday claimed that CCG vessel 5205 had “directly and intentionally rammed” the 97-metre BRP Teresa Magbanua, one of the PCG’s largest coast guard cutters. No injuries were reported. In a separate statement, the Department of Defense condemned China’s “unprovoked aggression” and said that it “remains steadfast in upholding its sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the West Philippine Sea.” (The latter is the term Manila uses for its portion of the South China Sea.)

A CCG spokesperson quickly turned the accusation back on Manila, claiming that it was actually a Philippine ship, “illegally stranded” at the shoal, which had “deliberately rammed” a Chinese vessel. He pledged that the CCG ” will take the measures required to resolutely thwart all acts of provocation, nuisance and infringement and resolutely safeguard the country’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.”

This is the third such confrontation at Sabina Shoal over the past month, after Philippine and Chinese vessels collided on August 25 and August 19.

This intensifying Chinese pressure has prompted a growing strategic convergence between Manila and Hanoi, something that has been inhibited for a long time by the outstanding disputes that these countries have with each other in the South China Sea. Last month, a Vietnamese coast guard ship arrived in the Philippines for a four-day visit that involved joint exercises. In June of this year, Vietnam said that it was ready to hold talks with the Philippines to settle their overlapping claims to the undersea continental shelf in the South China Sea.

At the same time, Vietnam and the Philippines continue to take quite different approaches to their maritime disputes with China. Manila has chosen to defy China’s pressure campaign and to strengthen its relations with its security ally, the United States, and other close partners including Australia and Japan. Vietnam, dwelling in much closer political, geographic, and cultural proximity to China, has managed to express opposition to Chinese actions deemed to infringe its sovereignty, while reassuring Beijing of its peaceful intentions, a necessity given the economic and political importance of its relationship with China. As a result, China has seemingly turned a blind eye to Vietnam’s substantial expansion of its features in the Spratly Islands, while reacting with excess force to minor actions by the Philippines.

Despite their own unresolved maritime disputes, and their differing approaches to the South China Sea, Vietnam and the Philippines both stand to gain from closer maritime cooperation. The signing of a defense agreement by the end of the year could serve as proof that Manila and Hanoi’s unresolved disputes are no bar to greater unity in the face of Chinese assertiveness.