Last week at the United Nations General Assembly, some extra star power was in the air.

Academy award-winning actress and activist Meryl Streep spoke passionately on the sidelines to support the rights of Afghan women: “A cat may feel the sun on her face. She may chase a squirrel into the park… A bird may sing in Kabul, but a girl may not, and a woman may not in public. This is extraordinary. This is a suppression of natural law.”

Yet behind the scenes of the Hollywood megastar’s speech, something else was stirring as leaders moved to open criminal proceedings for the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) first case involving a country accused of discriminating against women.

Female foreign ministers from Australia, Canada, and Germany called for the Taliban regime to adhere to the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which Afghanistan ratified over 20 years ago. The announcement was also supported by the Dutch foreign minister, Caspar Veldkamp.

This important political move will set the scene for future legal proceedings before the ICJ in The Hague, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. It is part of a wider plan to apply international pressure to hold the Taliban accountable for Afghanistan’s obligations to protect human rights. It is expected that Afghanistan would have six months to provide a response before the ICJ would hold a formal hearing.

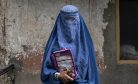

Since the Taliban seized power in 2021, women in Afghanistan have been systematically removed from public discourse by every measure. Over 100 edicts have been issued, including regulations to limit women’s access to parks, public baths, and gyms; banning women from travel without a male guardian; suspending women from working for national and international non-governmental organizations, including the United Nations, and more.

Women are not allowed to move around in public space unless accompanied by a male relative and covering their faces. They are also prohibited from raising their voices in public and are not allowed to be heard singing, reciting, or reading aloud outside of their homes.

Protections for women and girls facing gender-based violence, including safe houses, have been removed. Women are unable to work, attend school, or to look at men they are unrelated to by blood or marriage.

Afghanistan is also the only country in the world that has banned girls from secondary and higher education.

Those who have been following politics and life in Afghanistan for the last two decades know that the current situation is far from what once was: a landscape marked by a robust civil society, a growing class of women in politics, and even female tech entrepreneurs competing in robotics competitions.

Prior to the Taliban takeover in 2021, the Afghan Constitution required women to hold seats in parliament, and women held 27 percent of all seats in the legislature – not far behind the United States Congress, where 28.6 percent of seats are filled by women.

Afghanistan had established its first Ministry of Women’s Affairs, which has now been replaced by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. The country previously had more than 100,000 women enrolled in public or private universities.

These advances have been stripped almost completely.

“The situation of women and girls under Taliban rule is not just dire – it is catastrophic, with devastating consequences both in the immediate and long-term future,” said Belquis Ahmadi, senior program officer at the U.S. Institute of Peace “The systematic erasure of half the population, reducing their existence to something akin to ‘awrah’ – a term meaning parts of the body that must be concealed – reveals an unprecedented level of misogyny that is both mind-blowing and deeply troubling.

“Stripping women of their rights, barring them from public life, education, employment, and access services effectively confining them to their homes go beyond marginalization; they reflect a deeply ingrained perception of women as mere sexual objects, whose primary role is to bear children. It signals a return to medieval views, where women’s sole value is tied to their biological functions, with no regard for their intellectual, social, or economic contributions,” Ahmadi continued.

In a world facing conflict in Ukraine and a sweltering crisis in the Middle East, it is all too easy for the international community to look the other way. Yet Afghan women need attention more than ever.

If anything, their continued resilience, courage, and enduring strength are reminders of the vital role they can and must hold in shaping the country’s future. In light of these draconian restrictions, Afghan women have continued to be resilient. Many have enrolled in midwife training programs run by the Taliban’s public health ministry, now the only government-approved education program for women beyond grade six. Some have also sought alternative options for education including attending online school, while some have risked their lives to gather in homes. Others even continue to hold public demonstrations despite the threat of imprisonment and abduction.

Observers should continue to push for an ICJ case early next year, at the very least to place political pressure on the Taliban regime to recognize the rights of women and girls in the country. Further, as many have now called for international bodies to intervene, activists – including Pakistani activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafazai – are now calling for the criminalization of “gender apartheid” in international law. The term refers to the systematic and institutional oppression of women that has been so prevalent within the Taliban regime and, importantly, would set the stage for potent multinational legal action by applying a more robust international framework.

Afghanistan’s women have not stopped fighting, and neither should the international community.