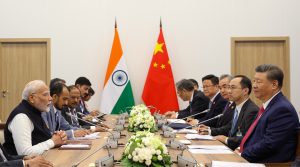

On October 23, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping held a delegation-level meeting on the sidelines of the 16th BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia. At the 11th BRICS Summit in Brazil in March 2019, the two leaders met in a bilateral set-up at the delegation level; in that sense, their meeting marks a return to normalcy.

Between the two BRICS summits, there was a prolonged freeze in China-India bilateral ties stemming from a stand-off along their disputed border. In June 2020, the Indian Army and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (Army) engaged in a deadly fist-fight in the Galwan Valley at the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh. India had accused China of advancing and making “exaggerated and untenable claims” concerning the LAC, and accused China of “hindering India’s normal, traditional patrolling pattern in this area” since May 2020.

The border clash in June 2020 led to the loss of lives on both sides, including 20 soldiers of the Indian Army and at least four from the PLA. This was one of the deadliest border clashes since the 1962 India-China War.

In reaction to the Chinese military aggression at the LAC, India deployed an additional 70,000 soldiers to the area. India also beefed up its defense installations, including Rafale fighter jets, and upgraded the infrastructure development along the LAC.

During this period, there was no political dialogue; only the military and diplomatic representatives from both sides held talks through different mechanisms, primarily the Working Mechanism for Consultation & Coordination on India-China Border Affairs, which met last on August 29 of this year.

The Background of the Breakthrough

On October 21, the day before the BRICS summit began, India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri, who until recently served as deputy national security adviser at the National Security Council Secretariat, announced a new border agreement with China.

Speaking at a Ministry of External Affairs press briefing, Misri revealed that Indian and Chinese negotiators had “been in close contact with each other in a variety of forums,” starting in July. That included a meeting between India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the sidelines of the ASEAN-related foreign ministers meeting in Laos on July 25.

“As a result of these discussions, an agreement has been reached on patrolling arrangements along the LAC in the India-China border areas,” Misri said. He added that the agreement between the two sides had led to “disengagement and a resolution of the issues that had arisen in these areas in 2020. And we will be taking the next steps on this.”

Jaishankar later hinted that 75 percent of the disengagement question had been resolved. Speaking at the Asia Society Policy Institute in New York on September 25, he added that “when I said 75 percent of it had been sorted out, I was asked in a way to quantify, to give a sense. It’s only of the disengagement.”

Following the current development, the disengagement process is seemingly completed. But as Jaishankar had noted in September, that was only one step of a larger process: “So there is what we call the de-escalation issue, and then there is the larger, the next step is really how do you deal with the rest of the relationship, because right now the relationship is very significantly disturbed.”

Will the Border Agreement Lead to Normalization?

The short answer is no. The agreement reached between the two sides only deals with disengagement and an understanding on patrolling, which has been affected since June 2020. There are two more key objectives to be achieved: de-escalation and, finally, demilitarization. Because of the cumbersome deployment of the troops in forward positions at the LAC on both sides, the situation remains tense.

This is not to say that a disengagement agreement will not be effective, merely that it will not lead to complete normalcy. Following Misri’s media briefing on the deal with China on disengagement, the Chief of the Army Staff Gen.Upendra Dwivedi said in a press conference on October 22 that “as far as we are concerned, we were looking at that we want to go back to the status quo of April 2020.”

Dwivedi further added that India and China “are trying to restore the trust,” which can only be achieved once “both sides can see and understand each other’s actions and intentions.” In doing this, “we must reassure one another that the buffer zones, which have been created as part of the disengagement process, are being respected and that neither side is maintaining forces in those areas.”

As the next step, India would like to normalize activities in the buffer zones, including military patrolling and normal grazing activities for the pets of the borderland communities. Demilitarization would further be crucial in ensuring normalcy as the conflict has placed a heavy burden on India’s military expenditure in the past five years. Meanwhile, a nod for demilitarization would only come from the military leadership on two sides since it is an operational matter.

With the resumption of the special representative-level talks on the India-China border, which plays a critical role “in resolving the boundary issue and maintaining peace in the border areas,” the possibilities for political dialogue will be explored further. National Security Adviser Ajit Doval is India’s special representative, while the Chinese side is represented by Foreign Minister Wang Yi. The two are expected to “meet at an early date and continue their efforts in this regard.” The special representatives have not held a formal round of talks in this format since December 2019.

The most crucial part of the process would be building trust between the two countries. There remains little doubt that trust on the Indian side will be strengthened by positive actions by China, because for a long time Delhi has experienced and accused China of violating all existing border mechanisms, including treaties.

This will also help ease the anti-China sentiments that have grown in India in recent years. The public opinion toward and media presentation of China in the country has been disheartening to Beijing. During a recent visit of an Indian delegation, including myself, at the invitation of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Chinese side expressed that “India must act to normalize discourse on China” in the Indian media.

On all practical levels, democracies have a way of reacting to territorial aggression, and expecting a change overnight may be too much to hope for, especially in India, which is regarded as the biggest democracy in the world and where public opinions often shape policies. During recently held parliamentary elections in India in April-May 2024, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party-led administration under Modi was criticized by the leading opposition, the Indian National Congress, over the border, with the Congress calling the June 2020 clash a “setback” to India.

What Comes Next?

The agreement on disengagement between India and China at the LAC marks a positive step toward normalcy. Still, looking at the complexity of the border dispute, a more comprehensive resolution would lead to building trust and opening up the full potential of economic and people-to-people ties.

At the launch of the Asia Society Policy Institute, Delhi, in August 2022, Jaishankar stated that “the state of the border will determine the state of the [China-India] relationship.” His statement wasn’t received well in Beijing. However, this reflected India’s defense preparation and ability to address any uneventful situation at the LAC.

India remains cautious and will tread carefully with China. This approach was well reflected in the Indian prime minister’s post on X after he met with Xi.

“India-China relations are important for the people of our countries and regional and global peace and stability,” Modi wrote. He added that “mutual trust, mutual respect and mutual sensitivity will guide bilateral relations,” hinting that further progress is essential if there is to be a true normalization of relations. The emphasis on “mutual trust” and “mutual sensitivity” signals that India expects China to address its concerns sincerely, without which the normalization process will remain incomplete.

New Delhi’s message is clear: a stable relationship with China is possible, but it must be built on actions, not just assurances. The ball is now in China’s court to demonstrate a commitment to this path.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Embassy in Delhi also quickly added its own post on X, saying that the “best way to advance the fundamental interests of China and India and their peoples is for both sides to keep to the trend of history and the right direction of bilateral relations.” In doing so, “the two sides need to strengthen communication and cooperation, properly manage their differences and disagreements, and facilitate each other’s pursuit of development aspirations.” The Chinese embassy’s position stands in sync with what Beijing has been conveying to New Delhi through the different platforms in the past few months, that both sides should engage without making a resolution of the border issues a precondition.

As the next step, Beijing will likely push India to reopen its doors to Chinese investments, which have been significantly impacted by the border tensions. Chinese businesses have reportedly expressed dissatisfaction over India’s resistance to these investments, viewing it as a pressure point that may have influenced Beijing’s willingness to ease tensions on the military front.

However, India remains cautious and is unlikely to welcome Chinese investments in the near term. Instead, New Delhi is focused on addressing the trade imbalance, particularly emphasizing negotiating a reduction of the current $85 billion trade deficit with China. For India, restoring economic ties with Beijing must be accompanied by more balanced and fair trade practices, ensuring that both sides benefit from the economic relationship.

The second immediate expectation for Beijing would be that India agrees to resume direct air connectivity between the two countries. Direct flights were stopped as a precautionary mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic, but in June 2020, the Galwan conflict aggravated the situation, and India decided to halt air connectivity with China. Since September 2024, the Chinese envoy in India has been advocating for the resumption of direct flights, adding, “We also expect positive measures from India in resuming direct flights and facilitating visas for Chinese citizens.”

In another reflection of the state of bilateral ties, the number of visas issued to Chinese citizens has been minimal. Global Times cited that India had issued just 2,000 visas to Chinese nationals in the first half of 2024.

To conclude, the recent agreements between India and China and the Modi-Xi meeting on the sidelines of the 16th BRICS Summit in Kazan have opened the door to a potential thaw in relations, but genuine normalization remains a pressing and distant goal. While the steps taken to de-escalate tensions along the border are significant, they are merely the beginning of a long process. Undoubtedly, restoring peace and tranquility in the border areas is just the first step – building mutual trust and addressing deeper issues must follow, which may take a few months if both sides are proactive.

Meanwhile, India’s cautious approach, emphasizing actions over words, underscores that normalization is possible only if both sides remain committed to this path. New Delhi has seemingly made clear that the onus is on China to demonstrate its sincerity through concrete steps, not just diplomatic gestures.